As housing emerges as a major election issue, it’s salutary to look to the past and examine some of the earliest debates and issues around social housing – and dispiriting to realise how little we have learnt.

This post looks at the first council housing built in Plymouth after the public duty to ensure decent housing for all was recognised in the 1890 Housing of the Working Classes Act. Much has changed since the worst days of Victorian slumdom but a closer look reveals some uncomfortable echoes with present-day problems and our continuing failure to fulfil that duty recognised – however falteringly – over one hundred years ago.  In the nineteenth century, Plymouth’s population was among the worst housed in the country. The first half of the century had seen three major cholera outbreaks and an epidemic of smallpox struck as late as 1872. The Corporation was slow to act – only adopting the 1848 Public Health Act six years after its enactment under pressure from the Board of Health.

In the nineteenth century, Plymouth’s population was among the worst housed in the country. The first half of the century had seen three major cholera outbreaks and an epidemic of smallpox struck as late as 1872. The Corporation was slow to act – only adopting the 1848 Public Health Act six years after its enactment under pressure from the Board of Health.

Minor improvements followed but the population remained grossly overcrowded. In 1890, over 16 per cent of the population inhabited two-room accommodation – a figure exceeded in only five other cities. In 1902, official returns showed 560 one-room tenements in the borough with four persons or more in each and 388 two-room tenements with seven persons or more. It was overall, in the words of the local Medical Officer of Health, ‘practically a tenement population’. (1)

Plymouth’s problems were compounded by its geography and patterns of land ownership – the Admiralty was a major local employer and landowner but provided little housing and, in fact, impeded housing development by sitting on land it controlled. In consequence, local rents were the highest in the country outside London according to the Board of Trade in 1908.(2)

Perhaps those problems of failures of land utilisation, housing shortage and inflated rents sound familiar.

At this time, Plymouth was one of the Three Towns (alongside Devonport and Stonehouse) and had become a county borough only in 1888. The new Corporation was to be more ambitious that its predecessors however, embarking – in 1895 – on its first municipal housing on land acquired on the town’s eastern outskirts at Prince Rock.

The Laira Bridge Road estate, comprising initially 104 flats and houses with accommodation for 824, opened one year later. Solid, attractive housing, the estate makes it into Pevsner which describes it as ‘red-brick with timbered gables, a conscious adaptation of the English vernacular idiom’.(3) Streets named after the members of the Housing Committee can be seen as an example of civic pride or personal self-aggrandisement according to taste.

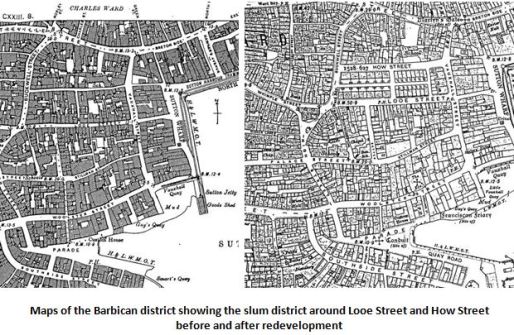

The estate was intended, in part, to rehouse those displaced by the Corporation’s other major pre-war scheme – a significant slum clearance project in the Barbican area, the town’s historic core. Seventy houses in Looe Street and How Street were demolished, affecting a population of some 813.

The first housing was built on the northerly side of Looe Street – a three-storey slate-roofed terrace of painted brick, concrete floors and staircases and wooden sash windows at the top of the street and a more elaborate, two-storeyed, timber-gabled further down – before 1900. How Street, adjacent, was completed in similar style.

The rents in both schemes were described as ‘high as against the wages of the tenants’ but ‘generally low as compared with the figure which could be obtained in open competitive market’ – figures ranged from 4s a week for the cheapest two-room flat to 8s a week for the most expensive four-roomed houses.

In Prince Rock, it was stated that very few tenants were earning more than 30s a week – a reasonable working-class wage at the time – and that most were earning around £1. This report continued: (4)

The occupations of the tenants may be described as those mainly of labourers, fishermen, and people of miscellaneous and more or less uncertain occupation. The distinct artisan class is almost entirely absent.

Over one third of the Prince Rock tenants were said to come from the former slums of Looe Street and How Street and most of the others were ‘from the same congested district…and of the same class’. If this was the case – and there seems to be some attempt to put a positive spin on things – this represented an unusually successful attempt to rehouse an inner-city slum population in Corporation housing.

By 1902, the Council had spent almost £50,000 on its central redevelopment scheme, a figure reflecting the relatively high cost of land, compensation paid to existing property owners and the extent of ancillary works. But the death rate in the district had been cut by almost four per thousand and the Council was clear that, ‘although the cost of the scheme has been heavy, the good results to the community’ were ‘very solid and apparent’.(6)

It may seem surprising, therefore, that the Housing Committee also concluded that it couldn’t ‘recommend the wholesale clearance of sites in this manner again, except in extreme urgency’. This brings us to the vexed question of finance.

Plymouth had incurred heavy debts in its programme of municipal enterprise – some resulting from the short thirty-year loans offered by the Local Government Board and some from bank loans. It was also accused of using earmarked loans for alternative purposes. As a result, it had been made subject to restrictions on its borrowing. (6) A private parliamentary act in 1904 regularised its position but required the Corporation undergo external audit.

The Committee had already felt itself compelled to sell off part of its building land at Prince Rock and build ‘housing of a less costly type’ in its central scheme. Its efforts at this point were concentrated on building tramways (to disperse an overcrowded population) and compelling repairs to existing slum properties.

Even under the restrictive terms offered by the Local Government Board, it was clear (as the Corporation argued) that its housing schemes were virtually self-financing – 1d on the rates met the immediate demand to service debt – and would be fully paid for within thirty years.

There is nothing new, therefore, in the financial short-termism which prevents councils borrowing to invest in much-needed housing or the crude fiscal calculus which proclaims the cost of everything but disregards the value – personal, societal, even economic – of investment in social infrastructure.

Nor is there anything new in the housing protest which results. In March 1900, the Plymouth branch of the Social Democratic Federation convened a meeting to establish the Three Towns Association for the Better Housing of the Working Classes. Despite the left-wing politics of the Federation, it ‘hoped that the matter would be considered from an entirely non-political and non-sectarian point of view’ and the party worked hard to forge an inclusive, populist alliance.

The origins and dynamics of the current Homes for Britain campaign are a little different but reflect, at least, the belief that the need for good quality housing for all should be a unifying rather than divisive issue.

The problems of creating such an alliance then (as now perhaps) were powerful. Against those in the upper classes (and the more ‘respectable’ working classes) who believed slum conditions were created by slum dwellers, the Federation argued: (7)

The refinement and worthy character which a love of home develops are impracticable to large numbers of people in ‘the merry homes of England’…. If the people were all heroes or angels of perfection they would, of course, surmount all obstacles, and keep themselves perfectly clean; but as they are only human there are some who, discouraged by the disabilities which a grinding capitalist system has imposed upon them, fall into dirty habits.

It’s an argument couched to appeal to those who would denigrate our poorest citizens but it remains a lesson that the makers of Benefits Street and its ilk might profitably benefit from.

Within the Association itself, a major division occurred when the Plymouth Cooperative Society decided in 1902 that its Building Society housing would be built for sale rather than rental. Against those who made the case that this would provide its members security for old age, an opponent argued Cooperators should:

cater for the thousands who would never be in a position to purchase a house. Who, he asked had been paying the interest on the land? Why the poor members, of whom there are hundreds waiting an opportunity to get a decent house to reside in, and here was a chance to help them.

As former philanthropic housing trusts and many housing associations across the country are looking to make money from selling off what they own or building homes for sale to the wealthy, this also has an uncannily modern ring.

Finally, there was the question of what social housing – council housing at this time – should be built. By 1906 the Corporation had rehoused a little under 1500 of a population (in 1901) of 107,000 and it embarked belatedly on another housing scheme in Prince Rock.

Some of these new homes turned out to be hard to let, a fact used by some councillors to oppose further council house building. The Association investigated and concluded that the rules against the keeping of fowl, rabbits or pigeons offended ‘the Englishman’s love of freedom’. More practically, the three-storey blocks in particular were criticised as barrack-like with poor facilities – washhouses shared between eight flats and ‘visits to the WCs…in the notice of the whole block’. (8)

A reminder, if we need it, that social housing tenants should never be second-class citizens, excluded from shared space, required to use ‘poor doors’, deprived of the light and views enjoyed by their better-off fellow citizens or – simply – in any way treated as inferior.

There’s nothing new under the housing sun. The moral, social and economic case for high quality and genuinely affordable social housing remains as compelling now as it was in turn-of-the-century Plymouth. Please support it in this election.

Sources

(1) The quotation – and other detail here – is drawn from Crispin Gill, Plymouth: a New History (1993). The 1902 figures come from ‘The Housing Problem at Plymouth’, Western Daily Press, Bristol, 11 December 1902.

(2) Mary Hilson, ‘Working-Class Politics in Plymouth, c1890-1920’, University of Exeter PhD in Economic and Social History, 1998

(3) Bridget Cherry, Nikolaus Pevsner, Devon, Volume 5 (1991)

(4) ‘The Housing Problem at Plymouth’, Western Daily Press, Bristol, 11 December 1902

(5) Mortality statistics are from William Thompson, Housing Up-to-Date (1907), the quotation from the Western Daily Press article cited.

(6) ‘Plymouth Corporation and its Borrowings’, The Nottingham Evening Post, 21 May 1903

(7) AT Grindley, ‘The Warrens of the Poor’, Three Towns Association for the Better Housing of the Working Classes (1906) quoted in Hilson, ‘Working-Class Politics in Plymouth, c1890-1920’. Other quotations which follow are drawn from the same source.

(8) Ann Bond, ‘Working-class housing in Plymouth 1870-1914’, Unpublished MRes thesis, Plymouth University, 2014

My thanks to Ann Bond for providing advice and detail for this post. Ann will know better than me the errors and omissions that remain.

Pingback: History Carnival 145: Elections, Bodies and Wars in History | George Campbell Gosling