Tags

I’m delighted to be able to feature another guest post, this by Sharon O’Neill. Sharon is a photographer and curator. Her work and research explores ‘the ordinary and unexceptional’ but shows how, when we take time to pause, we can find the exceptional in ordinary lives and settings. Full details of The Blueprint for Living exhibition and events celebrating the 60th anniversary of the Fitzhugh Estate are given at the end of the post.

Fitzhugh Estate (c) Flats series, Sharon O’Neill

The Flats series is a photographic exploration of one architect’s vision of the ‘modern world’ as told through the lives of the current inhabitants of one of his buildings.

Through a mixture of archive material and contemporary photographs the series delves into the everyday world of the occupants of a council block designed and constructed in the mid 20th century.

(c) Flats series, Sharon O’Neill

The work attempts to frame the young architect’s principles of modernism from the perspective of his idealistic vision of the 1930s. Using the building and interiors of the current inhabitants, it develops a photographic dialogue to illustrate his ‘modern world’, in essence, the realised future of his 1930s vision.

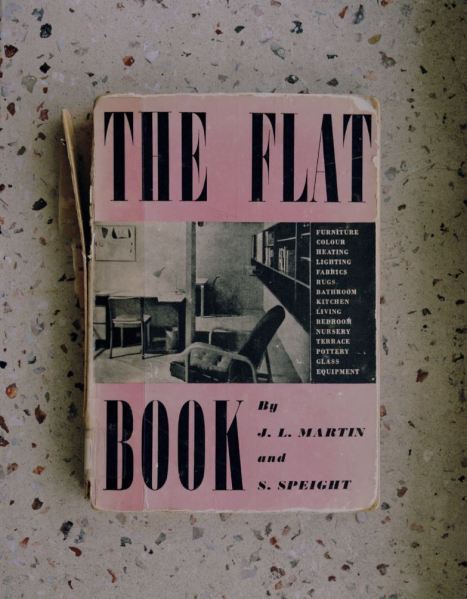

The Flat Book (c) Flats series, Sharon O’Neill

In 1939, the architect John Leslie Martin and his wife, Sadie Speight, published The Flat Book, which outlined their principles of design when living in the modern apartment. The introduction discusses the close relationship between planning and furnishing:

Furnishings…are affected in their design, like architecture itself, by similar radical changes in methods of production, changing social requirements and by the contemporary demand for convenience and efficiency. It is in these basic conditions that all style has its roots.

The book, essentially a catalogue of furniture, fixtures and fittings, offered ideas and suggestions on planning the living space and touched on new developments in the design of the flat, e.g. less space given to kitchens and bathrooms to provide a larger general living area.

Fitzhugh Estate interior in the Architects’ Journal (1956) (c) Architectural Press/RIBA Collections

In 1937, Naum Gabo, the Russian sculptor and painter, Ben Nicholson, the British abstract artist, and Martin edited Circle: international survey of constructive art, a book which aimed to highlight the British contribution to the European abstract movement and brought together their shared ideology that constructive art, architecture and design would improve people’s lives. The book included contributions from Piet Mondrian, Le Corbusier, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Barbara Hepworth and Walter Gropius among others.

Past and present: from the Architects’ Journal (1956) and Sharon O’Neill (c) Architectural Press/RIBA Collections and Flats series, Sharon O’Neill

In Circle, Martin wrote eloquently about the machine age and the idea that art, design, architecture and society were not separate entities, but were all elements of the same conversation.

Martin was one of a group of architects who truly believed a better society could exist where social problems could be solved through intelligent design based on the scientific approach of identifying the problem, research and analysis.

Fitzhugh Estate point block from the Architects’ Journal (1956)(c) Architectural Press/RIBA collections

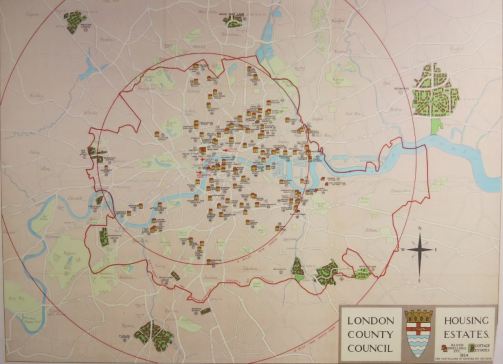

In 1953, work began on what was to be known as the Fitzhugh Estate, a collection of five eleven-storey point-block buildings set on the edges of Wandsworth Common and designed by Martin. Commissioned as part of the massive post-war building programme, the aim was to alleviate the desperate housing shortage. This was in part due to bomb damage, but also as a wider initiative by the post-war government to provide decent, healthy homes for low-income working-class families.

(c) Flats series, Sharon O’Neill

The architect and historian John McKean poignantly describes the mood in post-war Britain at this time:

The new social agenda centred on the concept of ‘fair shares’: the people’s war was to be succeeded by the people’s peace; its achievement would be seen in the national health and educational services and in popular housing for all.

Widely viewed as a significant period for British modernist architecture, modernism was embraced by the civic architects who were handed the task of rebuilding post-war Britain. The jewel in the crown was the Royal Festival Hall, designed by Martin in 1948 whilst at the London County Council Architects Department. The building is widely regarded as one of the masterpieces of post-war British architecture and Martin received a knighthood in recognition.

(c) Flats series, Sharon O’Neill

The LCC Architects department in this post-war period gained much admiration as the largest architecture practice in the world and with the brightest of British talent. Martin was deputy and then head of the department at this time.

Architects like Martin were celebrated in the exhibition A Place to Call Home at the Royal Institute of British Architecture where their role was highlighted as ‘crucial in framing a modern view of the world…they provided new and idealistic plans for housing and blueprints for living’.

(c) Flats series, Sharon O’Neill

The Fitzhugh Estate in Wandsworth, London, was part of this ‘blueprint’. Martin and his team designed state-of-the-art social housing that was featured in The Architects’ Journal in November 1956 (written as the first residents moved in). The building was lauded for its cutting-edge technology (using precast concrete and a 300ft tower crane to speed construction) and full central heating.

Originally the flats were built to provide homes for local working-class families, and were serviced by communal facilities to improve health, hygiene and provide a good quality of life.

Since their construction 60 years ago, the concept of the council estate has undergone a huge shift. Originally perceived as a ‘step up’, since 1980, when the dismantling of the council housing system began, it is more generally regarded as undesirable.

(c) Flats series, Sharon O’Neill

The block in Wandsworth is currently populated by a mixture of council tenants, those who purchased their flat through the Right to Buy Scheme and professionals who have bought properties on the open market either to live in or rent out, demonstrating a significant shift from the original demographic.

This series is an exploration of how the idyll of a young architect has stood the test of time as society has changed and how his ideas of design for the living space, as demonstrated in The Flat Book, may have permeated into the modern sensibility.

Fitzhugh tiling (c) Flats series, Sharon O’Neill

The work acts as an interpretation of Martin’s blueprint for living, a visual letter from the future back to the young architect of 1939.

The Flats series is part of the Blueprint for Living group exhibition showing alongside a film installation by award winning film maker Marc Isaacs and archive photographs from the RIBA Collections at The Fitzhugh Estate, Fitzhugh Grove, Wandsworth SW18 3SA from Tuesday 31 May – Saturday 4 June 2016.

Municipal Dreams will be in conversation with Owen Hatherley on Friday 3 June at 7.30 pm at the Blueprint for Living Exhibition. For more information on this and other events head to www.blueprintforliving.co.uk/events or http://architecturediary.org/london.

The exhibition is part of the London Festival of Architecture programme of events and the Wandsworth Heritage Festival.