Tags

We left Bristol last week in 1958 as slum clearance was in full swing and just as the Council announced plans to demolish a further 24,500 homes by the end of the century. By this point, however, such wholesale clearances – extended to areas of less severe housing deprivation – were arousing fierce opposition and that would have unintended consequences.

As local opposition mobilised, particularly among owner occupiers, the Labour MP for Bristol South, William Wilkins, raised concerns in a 1959 House of Commons adjournment debate, focusing on the issue of Compulsory Purchase Orders (CPOs). In Bristol, he cited 11 orders awaiting ministerial approval comprising 839 ‘pink’ properties (officially classified as unfit) and 453 ‘grey’ properties (capable of rehabilitation), of which 527 were owner-occupied. He cited local discontent and asked whether the Conservative Government felt that ‘they should abandon their slum clearance programme not only in Bristol but throughout the country’. (1) In this, Wilkins was some way ahead of of his time.

In 1959, a candidate of the Easton Homes Defence Association, formed to opposed demolitions, was victorious in local elections. In 1960, the Citizen Party (the local Conservatives in all but name) – which had been fanning the flames of local protest – secured an overall majority on the City Council.

The new administration set about reversing Labour policies by promoting private development on suburban estates and withdrawing the CPOs. But they encountered unexpected opposition when they met Henry Brooke, the Conservative Minister of Housing and Local Government. Brooke emphasised that he was: (2)

extremely anxious that slum clearance should go on and go on fast. I should be anxious that large numbers of houses which are represented by the Medical Officer of Health were being turned down by the City Council. I should be beginning to wonder whether, in fact, slum clearance was going on as fast as it should be.

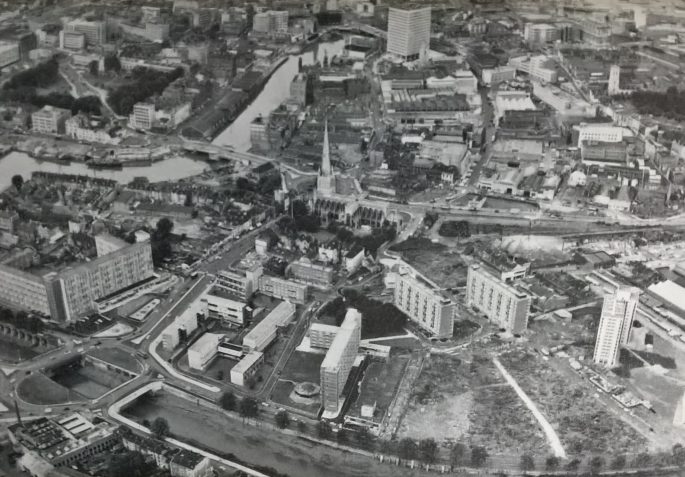

The political arms race at Westminster between Labour and Conservative Parties to build housing at pace and scale clearly took precedence over such local difficulties and the Bristol delegation returned home chastened. Central slum clearance proceeded and, ironically, in an attempt to make up the shortfall created by the axing of the Council’s suburban housebuilding programme, the construction of high flats in central areas was accelerated. In 1962, the proportion of high-rise approvals reached 99 percent. In the short term, the Council demolished 1300 more homes than it built between 1961-62, a fact contributing to Labour’s victory in the 1963 local elections.

This new phase of high-rise construction saw a shift in its locally predominant form – from slab block to point block. The former were criticised for their narrow access balconies which were not at all the ‘streets in the sky’ being pioneered in some deck-access developments of the day. Bristol was also becoming more typical in its reliance on a number of major contractors; Laing, Wimpey and Tersons won the bulk of local contracts.

What Bristol escaped, though seemingly more by happenstance, was the move to system-building. Bristol had been urged down this route in 1962 by Evelyn Sharp, the powerful Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Housing and Local Government (MHLG), and local councillors visited Denmark and France to see such methods in operation. But the Council was unwilling to offer the size of contract that the big builders wanted and the City Architect (now Albert Clarke) proved an awkward negotiating partner so interest waned.

The 13-storey Kingsmarsh House and 11-storey Moorfields House and Baynton House in Lawrence Hill were completed in the mid-1960s. Other point blocks were built just to the north in Easton in the later 1960s, including Croydon House, Twinnell House and Lansdowne Court at 17 storeys.

Into the mid-1960s, the Council also built high-rise in some of its suburban estates – three 14-storey blocks on Culverwell Road, Withywood (since demolished) and three eleven storey blocks on Hareclive Road, Hartcliffe, which remain. The usual case for suburban high-rise was mixed development – a variety of housing forms intended to serve a range of housing needs and to provide point and contrast in otherwise rather monotonous low-rise estates. In Bristol, it may also have reflected the Council’s need to build at scale when other options had closed or been closed.

The most interesting and controversial multi-storey schemes, however, occurred in Kingsdown. The Kingsdown I (Lower Kingsdown) redevelopment was underway by 1965, comprising six six- and fourteen-storey slab blocks. Carolina House was officially opened in October 1967. This large-scale incursion into an area of previously dense and intimate housing – some would say picturesque – was contentious but criticisms ramped up when it came to the Council’s plans for the upper slopes, Kingsdown II.

Here the original proposal for three linked 17-storey blocks was fiercely opposed by an increasingly active Bristol Civic Society backed by the Royal Fine Art Commission. (The Commission was authorised to draw government attention to any development which ‘in its opinion affected amenities of a national or public character’.) The MHLG rejected the scheme and also sharply criticised the Council’s somewhat half-hearted revised scheme for four eight-storey blocks. When the Citizen Party won a majority on the Council in 1967, the scheme was scrapped and the land sold to private developers. The High Kingsdown scheme which emerged – a courtyard development designed by Anthony Mackay of Whicheloe, Macfarlane and Towning Hill – is widely praised. (3)

Geoffrey Palmer, the leader of the new Citizen administration, declared in December 1967 that ‘apart from a few projects in hand, Bristol will build no more multi-storey flats’. Northfield House, in Bedminster, begun in 1969 was the Council’s last major high-rise scheme and – at 18 storeys – its tallest.

Whatever the local dynamics, in this Bristol was also reflecting national trends. Patrick Dunleavy emphasises the extent to which Bristol – like other local authorities – was heavily influenced by central government pressure, notably in the drive to clear the slums and build high in the early 1960s and in the reversal of that policy in 1967.

They heyday of high-rise – notwithstanding those projects in the pipeline – was over. The collapse of the system-built Ronan Point block in Newham in May 1968 is always taken as the major cause. In fact, alarm at the disproportionate expense of high-rise construction and a growing realisation that it didn’t rehouse at density (or that high density could be achieved better) were already making rehabilitation of older properties a preferred option of central government.

By 1971, there were 66 council estates in Bristol containing some 43,000 homes which housed just under a third of its 427,000 population. Within the total, there were 55 high blocks (of ten storeys or more) in the city forming around 14 percent of its total housing stock – a proportion higher than that in Manchester and Sheffield, for example, and the highest among what Dunleavy calls the free-standing county boroughs (a status it would lose in 1974 before becoming a unitary authority again in 1996).

This had been a frantic period of housing construction. Bristol had both followed and bucked the trends – pursuing the same path to higher-rise building as most of the larger cities but doing so in a local form, certainly in earlier years, and avoiding the pressures towards system building. Its slabs and blocks have generally survived – with the exception of some on the suburban estates – and seem to have stood the test of time better than many.

Sources

The website of the Tower Block UK Project provides detail on high-rise public housing in Bristol and nationally.

(1) House of Commons, Adjournment Debate on Slum Clearance, 13 May 1959

(2) Quoted in Patrick Dunleavy, ‘The Politics of High-Rise Housing in Britain: Local Communities Tackle Mass Housing’, PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 1978. Dunleavey’s research provides much of the detail that follows.

(3) A full account of the episode and description of the High Kingsdown scheme is provided by Elain Harwood in this online document.