If you think of Switzerland (beyond cowbells and cuckoo clocks), you probably think of it as one of the richest countries in the world – correctly so given that one in fifteen of its citizens are millionaires and average wealth per adult stands at around $700,000. You won’t, therefore, think of it as a nation of renters but only 43 percent of the population are home-owners, a fact reflecting the expense of home ownership, a restrictive mortgage market and the existence of a highly regulated private rental sector.

In Zurich, almost three-quarters of households rent and around one in four homes is owned and managed by a cooperative or public body. Currently, around 15,300 people live in municipal housing. What follows isn’t a comprehensive account of that history but a look at three main developments that I did get to see during a brief visit which, I think, are interestingly representative.

The modern city of Zurich was founded in 1893 (and expanded in 1934) but its roots can be traced to 1218 when it became a ‘free city’ within the Holy Roman Empire. In the fourteenth century, the power of guilds strengthened self-government and the city joined the Helvetic Confederation (that came to form Switzerland) in 1351.

Whilst the town and country’s political development were pretty unique, in other respects Zurich’s evolution was more typical of European industrialisation and urbanisation in the nineteenth century, growing from a population of around 17,200 in 1800 to 150,700 in 1900.

Two industrial suburbs were absorbed into the new city in 1893 – Wiedikon and Aussersihl, an area still known today as the ‘Industriequartier’. Housing conditions were poor and, in the (translated) words of the City’s own later account: (1)

it became obvious that neither the market nor a socially minded business or citizenry could provide any significant relief. Tuberculosis was a widespread disease, and social discontent threatened social cohesion. On the basis of in-depth studies on the housing supply, the city of Zurich decided for the first time to become active in housing policy itself: from now on, the city wanted to promote cooperative housing construction and also build apartments for particularly disadvantaged sections of the population.

It’s a familiar story – the state stepping in where the market and private philanthropy failed.

Wohnsiedlung Limmat I (Limmat Housing Estate I) was the result. A comprehensive, city-wide development plan had earmarked its location for housing in 1901. The scheme itself, designed by City Architect Friedrich Wilhelm Fissler, was completed in 1908, comprising three perimeter block buildings containing 253 apartments, around half of them three-bedroom apartments.

The estate was intended to provide a model that might be more widely emulated and it brought (in the later words of the City once more) ‘a touch of bourgeois aesthetics to the working-class district’. The former was seen in its decorative plasterwork, cornices and bay windows, and architectural details modelled both on English arts and crafts motifs and Zurich traditions. (Some of this detailing was unfortunately lost when the estate was renovated in ‘simplified’ form in the 1930s.) The innovation probably most favoured by the residents themselves were the blocks’ green, inner courtyards, still well used today when I visited on a sunny weekend.

In other respects, in order to keep costs and rents low, its accommodation was basic; the apartments lacked central heating and bathrooms. Surprisingly, it wasn’t till the 1970s that some of these deficiencies were made up. Initially, it had been proposed that the entire area be redeveloped along high-rise lines but ideas shifted towards urban renewal and the estate was granted a new lease of life through large-scale renovation. The apartments’ generous proportions allowed a bathroom to be added whilst keeping the living and dining area a decent size. Laundry and drying rooms located in attic floors were relocated to basements and additional accommodation provided. Last but not least, the apartments were provided central heating.

Alongside sponsoring various cooperative organisations, the City itself continued to build in the interwar period, in similar but adapted tenement block form but with the same attention paid to design aesthetic and estate infrastructure. (2)

Nevertheless, a new housing crisis emerged after the Second World War when rising prices and labour and materials shortages led to a real dearth of affordable housing. In April 1946, it was estimated 600 poorer households faced homelessness. The City provided additional loans to cooperatives and its decision to revive its own building programme, supported by 8 million Swiss franc loan, was endorsed in a referendum in August that year. (Significant policy and spending initiatives still remain subject to a vote by the local electorate.) By 1960, nine municipal estates and over 1000 apartments had been built.

The first of these was Wohnsiedlung Heiligfeld I built in a western suburb of the city between 1946 and 1948, designed by Josef Schütz und Alfred Mürset. The estate comprises 124 family apartments arranged in five tenement blocks, ranged on a north-south axis to maximise sunlight with alternating leafy, landscaped garden courts and service areas between. The form of the estate reflected new building and zoning regulations, confirmed in 1947.

Continuing building materials shortages led to some improvisation in the use of gypsum and slag. Glass fibre padding was inserted between floors and ceilings as it was assumed tenants would not be able to afford carpeting.

Kitchens, provided with electric stoves and ovens, opened onto the private balconies and dining rooms and each apartment had its own boiler to provide hot water. Heating, however, was both more rudimentary and ingenious. A wood stove placed at the centre of the apartment was expected to heat its entirety, feasible due to a floor plan in which rooms interconnected and ‘flowed’ one to the other. Doors provided the simple means to regulate temperature. (3)

Wohnsiedlung Heiligfeld II followed in short order, a long five-storey block – 71 apartments in all –running along Badenerstrasse, completed in 1950. This was simple three-room (i.e. two-bedroom) housing for the most part. While the flowing floor plan of its predecessor was abandoned, in its place the apartments were among the first in the city to be provided with central heating. This, however, was coal-fired and, to assist residents, a separate coal lift was built between pavement and coal cellar. A part-time ‘coal shoveller’ was appointed from the tenants to provide coal on a daily basis. Coal was replaced by a gas-oil system in 1987.

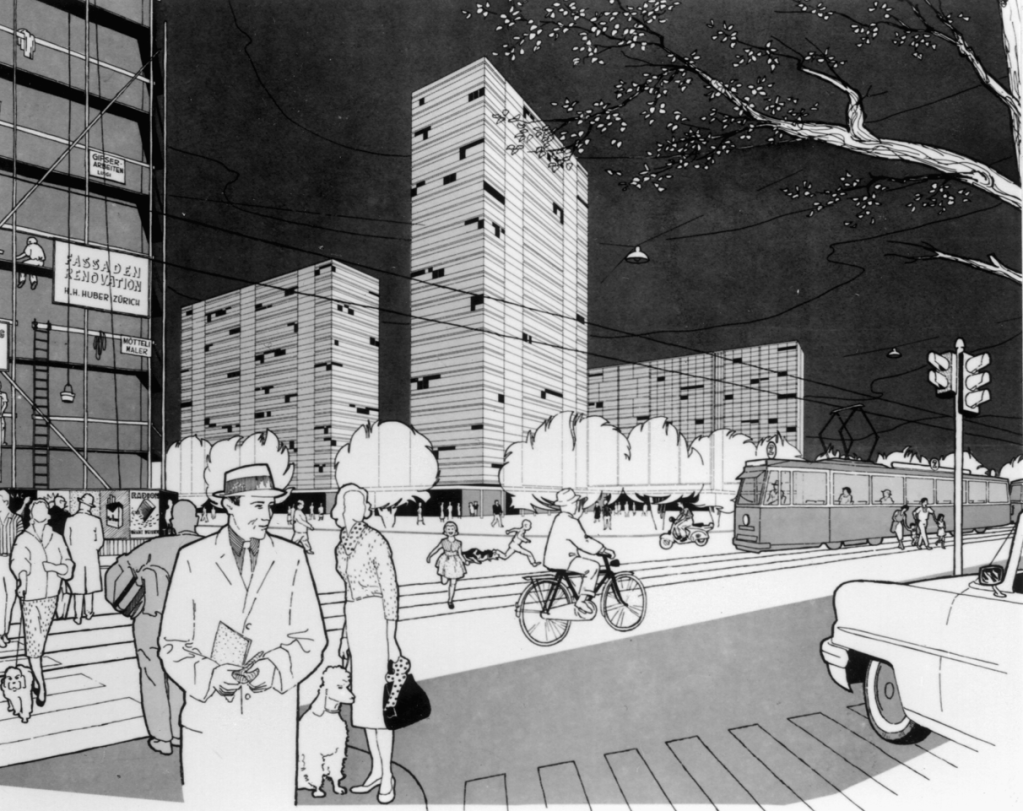

Although built just three years later, Wohnsiedlung Heiligfeld III marked the beginning of a new era in public housing design and provision, a decisive shift from the conventional tenement block construction that had dominated to date. The estate, designed by City Architect Albert H Steiner, contained Zurich’s first high-rise in the form of the two Y-plan twelve-storey blocks on Letzigraben and three eight-storey blocks. The blocks sit comfortably and attractively in a carefully landscaped site that was given equal weight in the ensemble. Landscape architects Gustav and Peter Ammann oversaw the planting; the architect Alfred Trachsel designed the playground and toboggan hill that was pioneering in its day.

The twelve blocks in all – including lower-rise elements – provided 151 apartments. To help new residents cope with the novel form of multi-storey living, Steiner commissioned two furniture companies and Willi Guhl’s interior design class at the School of Arts and Crafts to furnish some show apartments.

Significant renovation occurred in the 2000s. A number of smaller apartments were combined to provide four-bed homes in one of the blocks; the public park area was re-landscaped in 2003 and received the distinctive climbing tower and free-standing climbing rocks that are now a significant feature. Today, Heiligfeld’s estates – well-maintained and respected, set in generously landscaped, attractive green surrounds, and connected to the wider city by fast tram links – continue to provide first-rate public housing.

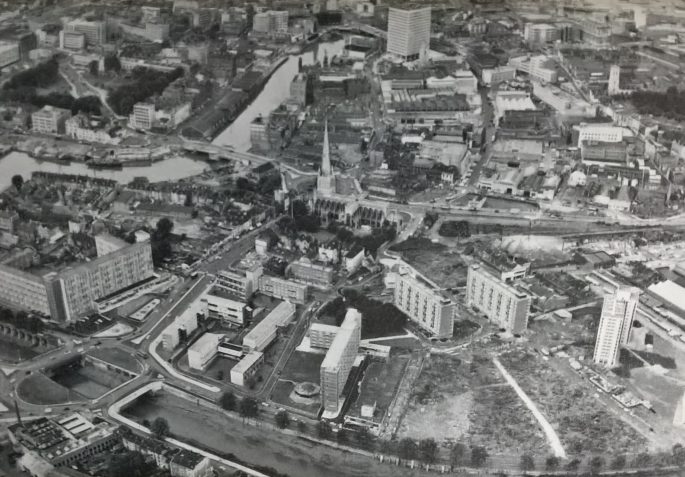

Housing remained in short supply in the late 1950s when the council acquired a significant opportunity to build at scale with its acquisition of a former industrial site just west of the city centre. At this time in Switzerland and elsewhere, planning ideas were shifting against the sprawling garden suburb development previously favoured. ‘Urbanity through density’ became the new watchword – the notion of higher density and mixed used development containing a greater mix of classes. Some described the goal as ‘a city within the city’.

In typical Swiss fashion, two steps followed. Firstly, in 1959, the City held an architectural competition to design the new estate. Karl Flatz was the victor with an ambitious scheme that contained one high-rise block rising to 28 storeys and provided a total of 461 apartments. Public disquiet saw the scheme reduced in height and size. The second step – the public referendum required to approve major schemes and expenditure – approved the project by 85 percent of the vote. Construction of Lochergut began in 1963; the first homes were occupied in 1966.

The finished estate comprised six main high-rise blocks: blocks A and D are 18 storeys high; blocks E, F and G are 15, 11, and seven respectively. In the middle, block C stands at 21 storeys. The ensemble is said to resemble a mountain range. From the higher storeys, of course, you can see real mountains as well as sweeping views of the Limmat Valley.

Beyond its 346 double-aspect, predominantly two-bedroom, apartments, the complex contains a generous range of community spaces and facilities – eight workrooms, a common room, a nursery, crèche and youth centre as well as a doctor’s surgery. The original somewhat gloomy subterranean shopping area was substantially re-designed in 2003. Underground floors provide parking for 980 cars and what is termed a ‘civil defence facility’; more joyously, they provide a plinth on which is built a thoughtfully planted and designed area that provides a pleasant garden for residents.

The City concluded its high-rise schemes with Hardau Hochhaus – unusually for Switzerland, four point blocks, the highest of which reaches 31 storeys, 95m in height. Designed by Max P Kollbrunner, the scheme was built between 1976 and 1978.

This account has looked, somewhat selectively, at municipal schemes in Zurich. In that sense, whilst local authority provision has been unusually important in Zurich, it provides a somewhat simple perspective. Miles Glendinning’s succinct account of Swiss ‘mass housing’ explains how limited federal funding has promoted housing in a range of tenures – housing cooperatives as well as private and municipal schemes. In Zurich, for example, in 1952, the five middle-class parties founded the arms-length Stiftung Bauen und Wohnen (the Building and Housing Foundation) as a means of avoiding direct public intervention. (4)

The result, however, obviously helped by the wealth of the Swiss state and the country’s commitment to high-standard public infrastructure, is a range of social housing – broadly defined – of unusual quality. Investment has been significant and ongoing. Schemes are architect-designed, generally awarded through architectural competitions.

To conclude, let’s look at the Siedlung Brahmshof, adjacent to the Heiligfeld estates, designed by architects Kuhn, Fischer, Hungerbühler for the Evangelische Frauenbund Zürich (the Evangelical Women’s League of Zurich) and completed in 1991. Beyond the buildings’ striking architecture and the attractive, well-used courtyard space, the scheme stands out for its social purpose. Its sixty-five apartments cater for a designedly mixed community – students, families, elderly people as well as people with physical and learning disabilities in shared apartments. The scheme also provides free social and legal advice for women, a children’s home and daycare centre. It’s a reminder of what housing associations with good funding and clear philanthropic goals can achieve.

Sources

My thanks to the City of Zurich for the excellent documentation of its housing schemes and the photographs provided under a Creative Commons licence by the Baugeschichtliches Archiv.

(1) City of Zurich, Limmat I Zürich Industriequartier Siedlungsdokumentation Nr.1 (ND)

(2) Images courtesy of Caspar Schärer, Von der Disziplinierung der Stadt zum urbanen Archipel Genossenschaften formen Zürichs Stadtbild, 31 October 2016

(3) City of Zurich, Heiligfeld I Zürich Wiedikon Siedlungsdokumentation Nr.12

(4) Miles Glendinning, Modern Mass Housing (Bloomsbury, 2012) pp215-218

To see Zurich’s municipal housing in greater range and detail, it’s well worth looking at the following webpages: