Tags

I’m pleased to feature the second of Jane Kilsby’s superbly researched and illustrated guest posts on some of the finest rural council homes in the country. Last week’s post examined the background to their construction; this week’s details their form and tells the story of those who designed and built them.

Banbury Rural District Council (BRDC) in North Oxfordshire did not build any council houses before 1914. In part I, we saw how the council members, the ‘Foxhunters, Farmers and Parsons’, made a decision to build before the outbreak of war but were overtaken by events. (1) Then, with the Addison Act of 1919 to spur them on and in the space of 18 months, they built 170 houses for the benefit of local farmworkers and returning soldiers.

Courtington Lane, Bloxham. Photograph June 2017

BRDC’s first council houses are only a fraction of the 170,000 or so completed in the early tranche under Addison, but they were described at that time as ‘the best and cheapest houses in any rural district in the country’. (2) Let’s have a look at who designed and built these stylish, comfortable houses.

BRDC had clear ideas about the type of houses they wanted to build. They wanted to see stone, not bricks, and local Hornton stone at that. They wanted the houses to be in or very close to each village with attractive views over the countryside and large gardens. High ground was their preference for ‘healthy homes’.

Sanitary Inspector, Mr Gander put himself forward as architect. He had done some training in an architect’s office before the War and had valuable local knowledge. The Housing Committee was pleased to make him their architect on a salary of £150 per year on condition that he appoint his son – still in the army – full time to help with all of his duties: Surveyor, Sanitary Inspector and now architect. The Committee’s appointment, however, was very quickly revoked. Councillor Crawford-Wood said:

the public are disgusted with this piling up of dual and triplicate offices on one man when other men require jobs.

The Local Government Board’s Housing Inspector agreed with their decision. His advice was to take on a qualified architect; any additional salary that would have been paid to Mr Gander would not be covered by the Local Government Board loan. As Councillor Dr Thorne put it, we will ‘have to get an architect with a grand brass plate in front of his house’.

And so they did. The council decided to appoint an ‘architect who has served in HM Forces and whose work has been interfered with so doing’. They approached the Architect’s War Committee – set up by RIBA to find work for architects returning from the War – and received ‘the names of four gentlemen recently demobilised to carry out the architect’s work’. Mr T Lawrence Dale of Richmond produced his drawings and testimonials at interview. Very impressed, the Council appointed him with the proviso that he could start at once and would open an office in Banbury. The Council agreed to pay him the RIBA-recommended fees (£2500) and reimbursed him his first class rail fare from London. Dale opened an office at 6 Horse Fair and took on an assistant at £6 a week.

Thomas Lawrence Dale (1884-1959) was born in London. He trained at The Architectural Association School of Architecture, the AA. He qualified in 1906 and became an Associate of RIBA the following year. In 1914 he had his own practice in Bedford Row. A Captain with the Army Cyclists Corps, he was mentioned in despatches. Before the War his commissions included houses in Hampstead Garden Suburb and Horn Park in Dorset, now Grade II listed.

A drawing by T Lawrence Dale of a terrace of four houses appeared in the Banbury Guardian in 1919. A terrace of four houses was built for BRDC in 1920 by Henry Meckhonik of London.

Lawrence Dale’s name in the render of one of the houses in The Firs, Wroxton

The summer of 1919 was a whirl of activity. The Housing Committee met fortnightly with an earlier start time of 10.30AM. Mr Dale’s plans were approved by the Local Government Board, BRDC appointed a Housing Clerk and land deals were done across the district.

The council had an initial loan of £122,270 for the building work and the land. Terms of repayment were variable; a 60 year repayment period at 6 per cent interest was typical. The Council needed temporary loans from its own banker, however, pending the raising of permanent loans, indicating the pace and extent of their activity. Rents needed the Ministry’s approval; in 1920 the rent for a parlour type house was 7s 6d a week, non-parlour houses were 6s a week.

Dr Addison, MP and Minister of Health wrote to the Council in July expressing his appreciation of their progress.

The ten houses in Upper Wardington were the first to be completed. They were let by Christmas 1920. Photograph June 2017.

The Housing Committee had made a tour of these houses in August 1920

Lawrence Dale designed at least two distinct types of houses for BRDC: the ‘A1 south’ type and the ‘Cropredy’ type. The A1 south type has ‘a parlour, large living room, kitchen range grate, cement-floored scullery, a washhouse with a boiler and space for a bath and a shed for fuel and potatoes.’ There were rainwater tanks with a capacity of 200 gallons outside at the back of each house. The Cropredy type has a larger entrance hall and steel window frames.

There are three pairs of semis of the ‘A1 south’ type in South Newington. BRDC bought the land from Magdalen College for £175 in 1919. The building included the provision of a septic tank. Photograph June 2017.

A ‘cottage’ non-parlour style was also used, for example, in Adderbury. Some of the developments contain a mix of styles, at Hook Norton, Drayton and Milcombe, for example.

The ‘Cropredy’ type houses in Barford St Michael have flank walls of brick. A well was sunk here by the contractor, another local builder, A Hopcraft and Sons of Deddington. Photograph June 2017.

Cottage-style semi in The Crescent, East Adderbury. 200 men from Adderbury and Milton went to the War. These houses were let specifically to returning soldiers and their families. (6) Photograph June 2017.

A pair of semis in Milton, with very large front gardens, built by the Harpenden Building Co. Photograph June 2017

The houses in Mollington are in the centre of the village and on higher ground. Lawrence Dale grouped houses together as much as possible ‘on the assumption that neighbours should also be friends’ (2). Photograph July 2017

Some of the cottages have names carved in a stone lintel above the front door. Thisbe and Pyramus Cottages are in Wroxton and the six in Cropredy were all named to commemorate the Battle of Cropredy Bridge, 1644. Charles, Cleveland, Cavalier, Culverin, Kentish and Waller Cottages are in Chapel Close.

Every house had a garden of not less than a quarter of an acre, double the Ministry of Health’s requirement for new rural houses. Council-built housing was a brand new concept in these villages: there was a concern that a lot of people thought that they would not be allowed to build pig sties. The Banbury Advertiser reported the Chairman’s insistence that:

where there was a large garden there should be a sty. He hoped the Press would note that there were no conditions of any kind whatever which prevented tenants putting up pig-sties.

The Banbury Guardian of 26 August 1920 was very complimentary:

The old idea of building a modern cottage was to put up four straight walls with a sort of box roof, the whole being severely plain, and, if economical, was exceedingly ugly. The council set out to resist the promulgation of these atrocities and the Housing Committee through their architect, Mr Dale, have produced cottages which do not detract from the picturesqueness of the villages, as was dreaded would happen when new buildings were called for.

The article noted too the striking form of the new houses:

the fronts, sides, and in some instances the backs, are of stone up to the roof, which is the mansard type, that is it breaks the front and back lines and is continued down over the first floor, but at a greatly reduced angle so that it does not curtail the space inside.

Walton Close, Bodicote. This site was one of the very few that had a water supply before the houses were built. Photograph June 2017

All of the Lawrence Dale houses have mansard, ‘cat slide’ type roofs. The houses in Horley have Hornton stone on all sides. Photograph June 2017.

There is no need to describe the interior of the houses when we have the film. The Hook Norton Village website includes 24 Square Miles Re-visited made in 1992.

This shorter film of highlights includes footage of the houses in Tadmarton. At about 9 minutes 22 seconds in, the film stresses that in 1944 the houses still had sinks but no taps and indoor toilets that were only a bucket. As BRDC knew only too well, good houses are only as good as their location and their water supply. (3)

The Tadmarton houses are on the hill in the distance, as in the film Twenty Four Square Miles. Mrs Summers, a widow who lost two sons in the War, was the first tenant of no 6. Photograph July 2017

Henry Boot steps into our story in 1920. Joiner and builder from Sheffield, he set up his company in 1886 and achieved rapid expansion. The company was the first building company to be listed on the London Stock Exchange. In the same year, 1919, Boot’s eldest son, Charles, took the lead. With a keen interest in house building, his company’s prospectus of 1919 refers to the ‘immense field for commercial enterprise opened up by this enormous volume of construction’. (4)

Henry Boot (1851-1931). Photograph with the kind permission of Henry Boot PLC.

Building contracts under the Addison Act started with an average size of 40 dwellings and, for contracting purposes, most local authorities split any planned large estates into small lots and this suited the building firms operating at the end of the War. As more councils began to build – there were 4,400 ministry-approved council housing schemes by 1922 – they needed economy of scale and speed.

With inflation and a scarcity of labour and materials, many smaller firms struggled to get finance. The work was there but they needed capital to get their schemes off the ground. BRDC had some experience of this; there were no difficulties with quality but some tender advertisements had a poor response.

Crucially, £300,000 raised as capital through their flotation gave Henry Boot & Sons the edge. The company was able to take advantage of the option to submit prices for groups of villages.

In April 1920 the Housing Commissioner received a proposal from Henry Boot that the company take on all of BRDC’s remaining sites and those of adjoining districts, including Towcester RDC. Boot’s offer was accepted. Charles Boot hosted a meeting at his London office in July attended by the Housing Commissioner, Lawrence Dale and Mr Fisher to thrash out details of the contract, including an agreement that the council would pay for building materials as and when they were delivered on site.

In April 1920 the Housing Commissioner received a proposal from Henry Boot that the company take on all of BRDC’s remaining sites and those of adjoining districts, including Towcester RDC. Boot’s offer was accepted. Charles Boot hosted a meeting at his London office in July attended by the Housing Commissioner, Lawrence Dale and Mr Fisher to thrash out details of the contract, including an agreement that the council would pay for building materials as and when they were delivered on site.

Boot & Sons built 128 of the 170 houses. Operating concurrently on 16 sites, the value of their contract was £126,934. Their work included the larger sites e.g. at Hook Norton (26 houses), Tadmarton (14), East Adderbury (22). Local carpenter, Percy Alcock, quickly became Boots’ foreman and then site agent for all 16 sites.

Houses under construction in Horley, 1920. Percy Alcock, Henry Boot’s site agent, is on the far left. One of the first lettings was to a Mr Green who had lived in an old cottage on this site. Photograph with the kind permission of PR Alcock and Sons.

Henry Boot & Sons (London) Ltd in the render of a house at The Firs, Wroxton

Distinctive ‘snail-creep’ pointing by stonemason Mr Cronk (employed by Boot & Sons) on the front of one of the houses in Shutford Road, North Newington. This is said to be very high quality ‘snail-creep’, an unusual technique in buildings faced with Hornton stone. There are BRDC 1921 plaques on many of the houses.

With so much going on, transport became an issue. Mr Gander was already using a council-owned motor-bicycle; the council bought a Ford light van and a motor-bicycle and side-car for Boots’ foremen on condition that they would be auctioned at the end of the contract.

There are three pairs of semis in The Close, Great Bourton. BRDC acquired this site under a compulsory purchase order. A shortage of tiles led to a delay in completion. Photograph June 2017.

By August 1922, all 170 houses (106 parlour type and 64 non parlour) were complete and let. Notices were put up in the villages asking anyone who was interested in a tenancy to get in touch with the Clerk to the Council, Mr Fisher. The council tried to offer the houses to local people from the same villages, with preference given to people who had served in the War.

And what did they all do next?

The ‘foxhunters, farmers and parsons’ continued to build council houses. Their later additions made use of the Ministry of Health’s standard house designs. Their successors, in tweeds, are portrayed towards the end of Twenty-Four 24 Square Miles.

Mr Gander retired through ill health in November 1921. BRDC was so appreciative of his loyalty that they kept him on as a Consulting Surveyor at £75 per year. What’s sauce for the goose? He died in 1925.

Edward Lamley Fisher, MBE, BRDC’s first Clerk, retired after 55 years of service. As Superintendent Registrar he had officiated at over 3000 marriages. In January 1945 at a party to celebrate his 50th anniversary at the council, his colleagues recalled the ‘extremely interesting and happy days just after the last great war…working with Mr Fisher on matters appertaining to the selection of sites for council houses’.

Lawrence Dale had a successful career; he became Oxford Diocesan Surveyor in the 1930s, designing and renovating parish churches.

Ickford Village Hall, Buckinghamshire, designed by T Lawrence Dale and Simon Dale in 1946; a style that will be familiar to residents of BRDC’s first council houses.

Charles Boot died in 1945 but not before Henry Boot & Sons had built more houses between the wars, public and private, in the UK than any other company. They built 20,000 council houses before 1930. With offices in Paris, Athens and Barcelona, the company diversified very successfully into building hospitals and bridges. They built Pinewood Studios in 1935. Henry Boot plc today specialises in commercial buildings and plant hire.

Laid off at the end of the Boot contract, site agent Percy Alcock formed his own company in 1922 with Cronk, the stonemason. PR Alcock & Sons continues today from their Banbury yard, carrying out high quality restoration and joinery works on period houses and churches and for the National Trust.

The houses themselves stand in settled peace. Most of them have been sold under the Right to Buy and change hands infrequently, the parlour types at a minimum of £450k. Sanctuary Housing Group manages those available for rent, for Cherwell District Council. There are interesting examples of the use of the huge plots but most of the gardens remain intact. Some of the houses are in Conservation Areas.

Wykham Lane, Broughton. The 1920s gardens were wide enough to accommodate new bungalows built in the 1950s. Photograph June 2017.

So, are these the ‘best and cheapest houses in any rural district in the country?’ They are probably not the cheapest. The 1920 Fabian Tract on Housing puts the average cost of a parlour-type house, at January 1920, at £803 per house, excluding the cost of the land, road-making and sewerage. (5)

BRDC had a ‘rule of thumb’ – house and land price – of £1,000 for each architect-designed cottage. The council’s accounts were done separately for each site: the Sibford Gower site of six parlour-type houses, for instance, cost a total of £4,945 15s 1d – that’s £824 5s 10d per house – very close to the Fabian average. Whether BRDC’s costs were included in the Fabians’ calculation is unclear. Value for money? Certainly.

South Newington. Photograph June 2017.

Thisbe and Pyramus Cottage, The Firs, Wroxton. Photograph June 2017.

The Old Council Houses, Horley. Photograph June 2017

The best? I can do no more than continue to quote from the Banbury Guardian’s description in August 1920, when the first houses were nearing completion:

the use of the word cottage seems hardly correct…the new houses might be called bijou villas.

Sources

(1) A phrase used by Arthur Gregory of SW1 in a letter to the Banbury Advertiser published 13 March 1919. ‘The foxhunters, farmers and parsons have monopolised the councils far too long, and it is time the co-operator, smallholder and the officials of the Agricultural and Workers’ Unions took their place and do what they can in the interest of progress’.

(2) Banbury Guardian, 26 August 1920

(3) 24 Square Miles Re-Visited a film made by South News, distributed by Trilith Films, 1992

(4) RPT Davenport-Hines (ed), Business in the Age of Depression and War (Routledge, 1990). Includes Cash and Concrete: Liquidity Problems in the Mass Production of ‘Homes for Heroes’ by Sheila Marriner.

(5) CM Lloyd, Housing, Fabian Tract No. 193 (1920), p11

(6) Nicholas Allen, Adderbury: A Thousand Years of History (Phillimore & Co.Ltd, 1995)

Contemporary quotations from the press, unless otherwise credited, are taken from the Banbury Advertiser and Banbury Guardian between 1911 and 1925 held by the British Newspaper Archive.

My thanks to the Oxfordshire History Centre of Oxfordshire County Council for making available the BRDC council minutes from 1921.

The council’s first Clerk was Edward Lamley Fisher. He was appointed in 1895. Solicitor, Registrar and Clerk to the Poor Law Board of Guardians, he is credited in the local newspapers for his knowledge, humour and urbane manner.

The council’s first Clerk was Edward Lamley Fisher. He was appointed in 1895. Solicitor, Registrar and Clerk to the Poor Law Board of Guardians, he is credited in the local newspapers for his knowledge, humour and urbane manner.

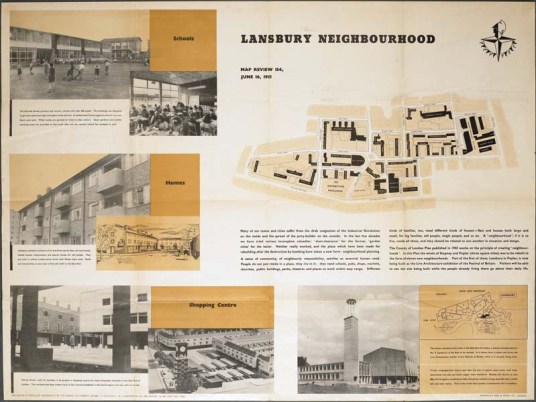

The Estate epitomises the ‘neighbourhood unit’, a key element of post-war planning envisaged as a means of preserving and enhancing an ideal of ‘community’ which some felt betrayed by larger, more anonymous council estates such as Becontree. Its centrepiece was Frederick Gibberd’s Chrisp Street Market and clock tower – the first pedestrianised shopping centre in the country.

The Estate epitomises the ‘neighbourhood unit’, a key element of post-war planning envisaged as a means of preserving and enhancing an ideal of ‘community’ which some felt betrayed by larger, more anonymous council estates such as Becontree. Its centrepiece was Frederick Gibberd’s Chrisp Street Market and clock tower – the first pedestrianised shopping centre in the country.

Neither of these appear in Open House but two of Lubetkin’s schemes for the Finsbury Metropolitan Borough Council – one of the most progressive in the capital – are featured. Bevin Court was opened in 1954; the Cold War having put paid to plans to name the building after Lenin (who had once lived on it site). Its innovative seven-story Y-shape capitalised on its site and ensured none of the flats faced north but, visually, its crowning glory is its central staircase. Visit to see that and the newly restored Peter Yates murals and bust of Bevin in the entrance lobby.

Neither of these appear in Open House but two of Lubetkin’s schemes for the Finsbury Metropolitan Borough Council – one of the most progressive in the capital – are featured. Bevin Court was opened in 1954; the Cold War having put paid to plans to name the building after Lenin (who had once lived on it site). Its innovative seven-story Y-shape capitalised on its site and ensured none of the flats faced north but, visually, its crowning glory is its central staircase. Visit to see that and the newly restored Peter Yates murals and bust of Bevin in the entrance lobby.

I hadn’t intended this tour of some of London’s finest council estates to be so elegiac but the contemporary picture of social housing’s marginalisation and market-driven ‘regeneration’ creates a poignant counterpoint to the energy and aspirations of previous generations. If you visit any of the estates on show during Open House London, my plea to you is to think of them not as monuments to a bygone era but as beacons of what we can and should achieve in a brighter future.

I hadn’t intended this tour of some of London’s finest council estates to be so elegiac but the contemporary picture of social housing’s marginalisation and market-driven ‘regeneration’ creates a poignant counterpoint to the energy and aspirations of previous generations. If you visit any of the estates on show during Open House London, my plea to you is to think of them not as monuments to a bygone era but as beacons of what we can and should achieve in a brighter future.