Last week’s post looked at the controversy surrounding rival plans – one a more traditional cottage suburb submitted by Borough Engineer Bertie Robinson, the other an ostensibly more visionary re-imagining of community life proposed by the architect Sir Charles Reilly – for Birkenhead’s Woodchurch Estate. The former had been preferred by the Conservative majority on the Council and they had appointed the Liverpool architect Herbert James Rowse to ‘to draw up designs for the houses to be erected on the estate’. (1)

This plaque is placed at the main entrance to the estate on the side wall of a house on Ackers Road

To general surprise, Rowse, perhaps unwilling to work within the confines of a scheme suggested by the Borough Engineer, perhaps seeking some third way compromise, returned to the drawing board and, in January 1945, submitted an entirely new scheme. Labour pressed for reconsideration of Reilly’s plans but in March 1945, the Council – dividing again on party lines – endorsed those of Rowse. Building of the estate, after a twenty-year gestation, finally began in 1946.

Rowse’s 1945 plan from Architecture and Building News, 1950

Whilst he eschewed the social engineering proposed by Reilly, Rowse’s own proposals reflected the spirit and ambition of the time: (2)

The Woodchurch Estate is not a mere assemblage of houses placed on a plot ground in the maximum possible density and monotonous regularity of layout and pattern, after the manner of the vast unplanned and uncontrolled suburban development of the inter-war years: it is the architectural setting of a fully developed sociological conception of a community of people living within a defined neighbourhood, having a conscious identity of its own and equipped for the maximum possibilities of the full intercourse of such a community. The comprehensive character of this project makes it of outstanding interest.

For Rowse, the fulfilment of these promises lay in the layout, facilities and housing forms of his new estate.

The overall plan was ‘developed on the basis of the natural topographical features of the site’ with:

Every effort … made in the planning of the Estate to provide prospects of the attractive rural surroundings from every possible point and to allow the maximum amount of rural character to permeate the estate by means of planted green closes, forecourts, quadrangles, recreation spaces and allotment gardens.

Broad parkways divided the estate whilst a central square provided ‘for the social life of the community’ with shops, baths and assembly hall, community centre, cinema, library and clinic:

In contrast to the familiar monotony of streets or their suburban counterpart, the estate will present varied internal prospects of groupings of terraces and small blocks amidst trees and green spaces, having the general character of a contemporary version of the traditional English village scene.

For the 2500 houses of the estate, Rowse proposed brick of ‘good, common quality’ with ‘architectural interest … achieved by the application of lime-wash, pigmented in a range of quiet tones of yellow, blue, pink and grey, alternating with white’. His interest extended to their interiors – those of the first homes completed being ‘decorated in warm ivory shade on the walls and a pale shade of blue on the ceilings’. Criticism of this colour scheme led to a uniform white being applied externally by the early 1950s.

Rowse’s illustrations of Woodchurch housing from Architecture and Building News, 1950

The estate’s early housing reflects Rowse’s ambitions though, on a cold January day such as when I visited, those broad parkways can seem rather bleak.

Shops on Hoole Road © Rept0n1x and made available through a Creative Commons licence

Rowse’s supervision of the scheme was superseded by that of new Borough Architect TA Brittain in 1952 who, in Pevsner’s astringent words, ‘continued building to inferior standards of design’. The volume dislikes the estate’s early neo-Georgian-style shopfronts but reserves its greatest disdain for the Hoole Road shops, once planned as a centrepiece of Rowse’s central parkway. (3)

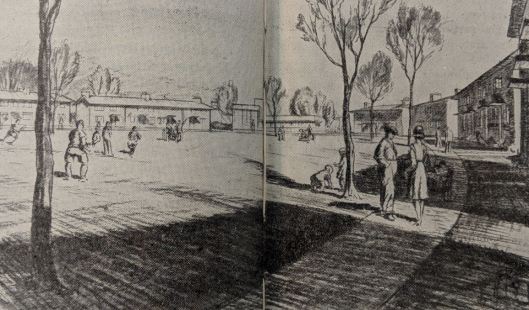

This early image closely resembles the 1000th house on the estate, opened in 1953

The estate’s 1000th home, no. 84 Common Field Road, was officially opened by local MP Percy Collick in 1953 – a gabled, tile-hung, arts and crafts-inspired design, clearly a legacy of Rowse’s tenure.

Early photographs of the estate

Later housing was plainer but the biggest departure from Rowse’s founding vision were the two 14-storey tower blocks – Grasswood Gardens and Ferny Brow Gardens – built in 1960 on New Hey Road; the architect, ironically was HJ Rowse. (4) By the end of the decade, three 14-storey blocks were added, built by Wimpey – Leamington, Lynmouth and Lucerne Gardens, at the Upton end of the estate.

Leamington, Lynmouth and Lucerne Gardens, photographed in 1987 from the Tower Block website

Typically, for all the preceding rhetoric, even the most basic community facilities were slow to appear: the first shops in 1953, a health clinic in 1954, and the first local library (at first housed in the new secondary modern school) in 1959. A community centre followed in 1965.

St Michael and All Angels, January 2019

Church congregations met in private houses or local halls until the Methodist church opened in 1958 and the Roman Catholic St Michaels and All Angels in 1965. The latter was worth waiting for, at least with an impressive modernist design (by Richard O’Mahony), planned liturgically – in Vatican II style – to focus attention on the central altar and – in landscape terms – to provide a fitting climax to New Hey and Home Farm Roads.

Home Farm Road, January 2019

All this, however, was some way away from the promises of Rowse, let alone Reilly, and that post-war vision of planned community. Later academic studies of the estate allow us to examine the community which did emerge. They present a mixed picture, both reflecting and challenging standard interpretations.

The new residents were predominantly young families. A points system determined priority, favouring ex-servicemen, established residency and size of family. Additional points were awarded to those living in unfit accommodation. They were also judged by their ability to pay the rent though this was often a struggle: an average rent for a three-bed home amounted to £1.40 whilst local wages ranged from £3.50 for an unskilled male worker to £5 and above for semi-skilled and skilled workers. In the struggle to make ends meets, cookers were often bought from the Gas Board and furniture from Sturla’s department store on the ‘never-never’ (hire purchase). (5)

Ganney Meadows Road, January 2019

In support of the Wilmott and Young narrative of ‘missing mum’ (or, more academically, missing inner-city matrilocal kinship networks), there were the many young women who trekked back on an almost daily basis from this peripheral estate to their parents. Some walked, some struggled with their Silver Cross prams (‘normally second-hand, mind’) on an inadequate bus service. One young mother with school-age children cycled to the Mount Estate – where her parents now lived – every day at 10am, having got up at 6am to clean the house and prepare evening meals. (5)

But there were others pleased to place some distance between themselves and family:

One male interviewee explained how he and his wife were glad to get away from his mother-in-law because ‘she was jealous of my wife’ and he described how the friction caused by the situation had put a strain on other family relationships.

As for community – or, more properly, neighbourliness – that was found informally, often in the revival of established friendships:

There was a knock at the door. When I went to the door there was [name] standin’ there with a tray an’ a pot of tea. We just couldn’t believe it when we saw each other’s faces. We’d lived in adjacent roads up near Bidston, had been good friends … childhood friends for many years … before the war an’ she was my next-door neighbour! I couldn’t believe it, it was like bein’ with family

Given that many people moved to Woodchurch at the same time from similar areas of central Birkenhead, these connections are not surprising, and, in due course, family links might also be resurrected as parents or siblings also moved to the estate.

Home Farm Road, January 2019

The much vaunted ‘spirit of a New Britain’ (discussed in last week’s post) seems absent but perhaps lived on in attenuated form:

It wasn’t just the fact that we were all from Birkenhead, we’d all been through more or less the same experiences … been in the same kind of housing … lost loved ones or our homes during the war. We were just glad to be alive an’ we weren’t goin’ to shut the door on a neighbour who needed a hand … where we came from it wasn’t the done thing.

But few came to look on the community centre as a centre of social life, still less civic engagement as had been hoped by post-war planners: a ‘number of the interviewees recalled that they only went there for Bingo “on a Tuesday night” or “when someone was havin’ a “do”.

In the end, ‘community’ developed very largely without the benign assistance of planners and politicians and, with hindsight, the would-be social engineering of the latter, however idealistic in motive, appears mechanistic in practice. Real lives were led domestically, within the interstices of home, family and friendship, with little reference to formal institutions and with little desire to think or act more politically or civically.

New Hey Road, January 2019

Meanwhile, older traditions of heavy-handed council paternalism lived on – though typically enforced by women housing officers raised on the Octavia Hill tradition. Miss Crook was clearly the local exemplar:

I mean, everyone I’ve spoken to about it remembers the way she used to check the beds – the sheets, the blankets an’ that – she’d run her fingers over surfaces to check for dust, an’ the look on her face if she found any! It was like ‘Not dusted today then, dear?’ … Well, she did congratulate me on the standard of cleanliness, but by the time she’d finished doin’ her rounds I was ready to explode. But we just had to put up an’ shut up. Y’didn’t argue with authority at that time.

Respectability and responsible tenancy were thus rigorously policed in these early years.

For all that, Woodchurch, in some eyes, developed a bad reputation. As early as 1952, a local newspaper article was headlined ‘Vandalism Sweeps Woodchurch Estate. £500 damage to bulldozer’. (The combination of many young children living on what were, in effect, huge building sites made such reports quite common across the country, in fact.)

Home Farm Road, January 2019

But as estates, such as Woodchurch, grew older, perceptions of them changed. Press reports of crime on the estate in 1969 led the police to come to its defence: ‘The incidence of crime and disturbances on the estate is no more serious than in several other areas of the town … isolated incidents had been taken out of context’. (7)

By the 1980s, however, as unemployment and, in particular, youth unemployment rocketed, there were real problems. Woodchurch (and even more notoriously, Birkenhead’s Ford Estate) became known as centres of heroin addiction: by 1983, it was claimed nine percent of 16-24 year-olds on the estates were taking the drug. ‘Woodyboy’ recalls the era: (8)

By the time my year finished our ‘O’ levels at Woody High in ’83 we well and truly knew what was going on around us. It seemed like everyone’s big brother or sister was a smackhead. They were the kids we remembered from primary school who were only a few years older. We knew kids in our year that had tried mushies or were into glue, but this was a whole different ball game.

The estate also became associated with wider problems of gang violence and antisocial behaviour.

Three ages of housing with Brackendale House to the rear, January 2019

From this time, there have been concerted efforts to raise the estate. In Birkenhead, tower blocks were seen as one cause of this new social malaise and the new Borough of Wirral (formed in 1974) had been the first in Europe to demolish some of its blocks – beginning with the central Oak and Eldon Gardens towers in 1979. On the Woodchurch Estate, the two New Hey Road blocks were converted to housing for elderly people and renamed in 1984. Now, only one – Brackendale – remains. Leamington, Lynmouth and Lucerne Gardens have also been demolished.

Today, the worst social problems of Woodchurch are over and, to this outsider, the estate looked generally well-maintained and cared for, and attractive in its older parts where Rowse’s vision was more fully implemented. It’s a council estate which means in modern Britain it houses disproportionately a poorer population and unemployment levels remain high. Four areas of the estate are among the ten percent most deprived in the country. (9)

There are some who would blame council housing for that. For me, it’s a manifestation of what has been done to council housing and its community. Whilst the Woodchurch Estate itself was one small part of the ‘New Britain’ to emerge after 1945, a wider element of that promise was full employment and reduced inequality. That is a promise betrayed and we have asked council estates and their residents to carry the burden of that betrayal.

Ganney Meadows Road, January 2019

One early resident of the estate recalls it:

as being as good as any private housing … people didn’t realise it was a council estate … it was peaceful too in the early days. It was a good place to live and a good place to bring up the children.

That, I’m sure, remains true for many today.

Sources

Kenn Taylor, who was raised on the estate, has also written interestingly on its history and significance in The Memory of a Hope.

(1) Margaret H Taylor, ‘Creating a Municipal Gemeinschaft? Disputations of Community’, Manchester Metropolitan University MPhil, 2013.

(2) HJ Rowse, ‘Woodchurch estate, Birkenhead; Architect: H. J. Rowse’, Architect and Building News, October 14, 1950. The quotations which follow are drawn from this source.

(3) Nikolaus Pevsner, Edward Hubbard, Cheshire (1978)

(4) Tower Block (University of Edinburgh), Woodchurch: Contract 23

(5) Taylor, ‘Creating a Municipal Gemeinschaft’

(6) As argued in Young and Wilmott, Family and Kinship in East London (1957). Woodchurch analysis drawn from Lilian Potter, ‘National Tensions in the Post War Planning of Local Authority Housing and ‘The Woodchurch Controversy’, University of Liverpool PhD, 1998. The quotations and later detail are drawn from Taylor, as is the following quotation.

(7) ‘Police Speak Up For Woodchurch Estate’, Liverpool Echo, 23 July 1969

(8) SevenStreets, ‘Smack City: Thirty Years of Hurt’ (ND, c2013). The statistic is drawn from the article; the testimony from comments below.

(9) Wirral Council Public Health Intelligence Team, Indices of Multiple Deprivation for Wirral 2015 (November 2015)