Tags

The Flower Estate in Sheffield doesn’t get the attention it deserves but it was a pioneering attempt by a progressive council to create good quality and healthy housing for its working population. And it illustrates how difficult this could be too.

Such housing was desperately needed in Sheffield. The town’s industrial workforce had expanded massively in the nineteenth century and housing conditions were correspondingly poor. In 1891, Sheffield’s Medical Officer of Health concluded:(1)

Such housing was desperately needed in Sheffield. The town’s industrial workforce had expanded massively in the nineteenth century and housing conditions were correspondingly poor. In 1891, Sheffield’s Medical Officer of Health concluded:(1)

it would be hard to find in any town poorer conditions of property and worse surroundings than are to be found in these central areas of Sheffield…In order to deal with the worst areas nothing less than radical measures will really avail. No mere abatement of the nuisances, so far as is possible under the existing conditions, will suffice.

Such complaints and pleas were legion as the full social impact of the Industrial Revolution became clear but there were rarely either the political means or will to address them.

At length, the means had been supplied, at least in part. The 1890 Housing of the Working Classes empowered local authorities not only to improve or clear slum housing but to build anew where necessary.

However, few councils took advantage of the legislation in its early years. The London County Council – as we’ve seen at Millbank and the White Hart Lane Estate – was one exception. Sheffield was another.

The key to both lay in their radical and ambitious politics. Sheffield had a proud tradition of working-class organisation and politics but the growth of heavy industry and the trades unionism that went with it by the end of the century now gave this a new cast – I’d say proletarian and collectivist if it didn’t frighten the horses.

By 1893, the Sheffield Trades Council – the federal body represent the city’s unions – was demanding a ‘forward Municipal policy, embracing improvements in working class housing, more libraries and parks and the municipalisation of monopolies’. And the city’s dominant Liberal Party knew it had to change with the times if it were to retain its influence.

A penumbra of socialists was also active in Sheffield. One, Edward Carpenter, was notorious, He was none too concerned with mainstream politics but he influenced many, including Raymond Unwin – then working to design miners’ housing close by in north Derbyshire – and Alfred Barton, a local member of the Independent Labour Party, elected to the council in 1907.

Unwin reminds us of the intellectual climate among housing progressives of the day. Philanthropic industrialists were building model workers’ estates at Port Sunlight and Bournville and Ebenezer Howard was promoting garden cities. Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker – who would go on to design the Wythenshawe Estate – were appointed architects to Letchworth Garden City, intended to embody Howard’s ideals, in 1903.

One year earlier, Unwin’s Fabian tract Cottage Plans and Common Sense, illustrated by Parker, had provided the ideal for these new workers’ homes.

Far more prosaically but of equal practical import, Sheffield had taken its tramways into municipal ownership in 1896 and completed the city’s network by 1913. The value of this – and the workmen’s fares which accompanied it – was recognised by the Medical Officer of Health who asserted that ‘the new and most excellent tramway facilities will do more to relieve the congestion in the central districts than anything else’.

Nevertheless, early Council attempts to deal with the local housing crisis had proved unsatisfactory. The expense of the first had led to the building of high-rent tenement blocks which some considered little improvement on what they replaced. The second – a piecemeal scheme making use of the council’s powers to force landlords to improve their properties – proved too slow and cumbersome.

Both were inner city schemes and their failure led the Council to embrace as necessity the ideal of suburban building. In 1900 the Health Committee paid £9100 for an area of greenfield upland at High Wincobank – to the north-east of the then city but close to Firth Park’s tramways and Sheffield’s east end steelworks.

The Council organised a national competition to design the workers’ cottages to be built on the estate. The winner was Percy Houfton, a Chesterfield architect, who produced two designs. Both avoided rear projections – seen as restricting fresh air and light – and included upstairs bathrooms and downstairs inside toilets. Class A houses were double-fronted, Class B houses single-fronted and suitable for terracing.

The designs were austere with none of the Arts and Craft touches typically favoured by the pioneers of improved workers’ housing but internally they exceeded the ideals of Unwin and Parker. They were expensive, however. Rents ranged from 7s 3d (36p) or 6s 6d (32.5p) per week for a three-bedroom house to 7s (35p) for a superior two-bedroom house.

This was a level of rent that led the Garden City Journal to conclude:

the standard of comfort aimed at is beyond the reach of the labourer, for this class the provision of housing remains unsolved.

The Council drew the same conclusion. Local architect HL Patterson was commissioned to design cottages to be rented at 5s (30p) a week. These may have been more affordable to local workers but they were smaller and lacked bathrooms. Twenty were built.

Despite this pragmatism, the Council remained ambitious. Having sent delegations to two Letchworth conferences in 1905, they hosted their own event in Sheffield, the Yorkshire and North Midland Cottage Exhibition in 1907.

In the event, it was the exhibition site’s layout which gathered most notice – the plan of William Alexander Harvey and Arthur McKewan, who had worked together at Bournville, praised for its innovative and picturesque quality, particularly its offset of corner buildings and incorporation of smaller greens and recreation areas within the larger design.

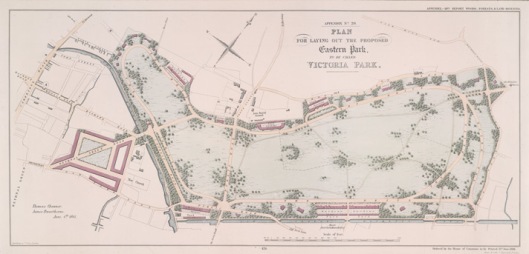

The 1907 site plan designed by Harvey and McKewan. The original Corporation estate can be seen to the bottom right.

The 42 model homes were less innovative but they incorporated many of Unwin’s ideals. One of the most attractive homes – though not a competition winner – was again the design of Harvey and McKewan. As the exhibition catalogue describes: (2)

The aspect of the various rooms have been carefully considered and the whole of the rooms would have sunshine during some part of the day. The coals, WCs, etc. have been kept under the main roof as far as possible, so as to avoid any unsightly projections at the back…A folding bath is provided in each scullery and an Ideal boiler for hot water is also provided.

Harvey and McKewan’s exhibition entry in 1909. Image s2611 reproduced with permission of Sheffield Libraries, Archives and Information.© Sheffield City Council Housing Department

In general, the exhibition entries were criticised for their rather unimaginative design and poor internal fittings and the Council’s decision to purchase the 42 houses was criticised by urban planners such as the young Patrick Abercrombie who hated their incoherent jumble of styles.(3)

Local Conservatives made a more telling point regarding the £8,391 purchase price. They complained that their necessarily high rents ensured that the Council was merely ‘providing dainty villas for already well-paid artisans’. This charge would be a major factor in the Liberals’ loss of power in 1908.

The Conservatives were to suffer their own housing fiascos and the Liberals duly returned to office in 1911. They resumed the development of the Flower Estate but the new cheaper houses were smaller and of much lower quality. Alderman Bailey reflected what had become a conventional view that ‘there was no hope of building houses on the Wincobank estate within the reach of ordinary working men’.

Ironically, the First World War would revise that view. In its aftermath the will and the means would be found again to fulfil at least some of the ideals of the Flower Estate. The pre-war estate totalled just some 230 homes. In the interwar period, Sheffield would expand its housing programme massively – as would many other municipalities. The housing designs and estate layouts pioneered in High Wincobank would prove a major influence.

The Flower Estate itself was completed in 1923. Stubbins and Brushes estates, begun in the interwar period, to the west in Firth Park both reflect garden city ideals as does the larger Manor Estate.

What all of these estates have in common, including the Flower Estate, is a narrative arc. The estates were founded with a practical idealism which seemed vindicated in their early years. Strong communities formed and, though the estates weren’t perfect, there was a general recognition that this was housing and an environment of far higher quality than working people had ever previously enjoyed.

And then from the 1970s these estates became the badlands – blighted areas of high-crime and social breakdown.

For anyone charting this trajectory, this response from the Sheffield Forum to the question ‘Flower Estate, what went on?’ is word perfect:(4)

I grew up on the Flower Estate and it did get really rough and tough in the late 70’s and 80’s. According to my parents (my mom lived on there from being a child) the estate was a nice place to live with a good community spirit until the slum clearances of the late 60s and 70s came along. This brought in a lot of problem families which were normally large in numbers.

Someone else comments on the Estate’s heyday, ‘it was a good estate back then. Everyone looked out for each other, you could leave your doors unlocked…’.

What apparently changed were the new residents and the problems they brought. At this point, apparently, it became:

easy to get a house [on the Estate] because no-one else wanted to live there. Before long it was full of undesirable tenants and families…Break-ins were daily, assaults and muggings regular, plus the drug dealing…

Perceptions define reality and none of this needs rebuttal, just context and some caution.

The context lies in economics – the collapse of Sheffield’s local economy and a massive rise in unemployment – and politics – housing legislation which had the effect of increasingly confining council housing to the most vulnerable or troubled. In combination, they altered the Estate’s demographics and ethos.

Even in 2005, in a period of relative prosperity, over one third of households in Flower were claiming Income Support, double the average in Sheffield. And the 3000 residents of the Estate would die, on average, six years earlier than even their more affluent local counterparts. By this time, incidentally, 42 per cent of houses were owner occupied.(5)

The caution is simply a reminder of ‘the number of decent folk’ that continued to live on the Estate and the lives lived quietly away from the headlines of crime and social breakdown.

In the event, the problems were considered so severe and some of the housing in such a bad state – though not the model housing described above – that large parts of the estate were razed. As is the modern way, a collaboration between private developers, the City Council and local housing associations is rebuilding – ‘affordable’ homes though very little of it for rent as far as I can see.

And within this nexus is a community. The Flower Estate Community Association was formed in the worse days of the 1980s, run, in its words, by a ‘few women, who have basically worked very hard and along the way have gained a wealth of experience and strong friendships’.(6) There are a battery of initiatives now and the Association is one of a number of local groups ensuring that the jargon of community regeneration has a meaning for the people who are sometimes treated as its subjects.

Its chair is optimistic:(7)

Some houses have been demolished, others refurbished and we see the new houses progressing each day. We are a nice small estate and it is getting better all the time. We are very proud. We have lovely people here and a thriving community centre

So that’s the Flower Estate. Judging by the response to the Forum question referred to above – there were 141 posts – there are a lot of people who know the Flower far better than me and care about the Estate deeply. I’ve learnt a bit about its history but Municipal Dreams aren’t abstract and I’d be pleased to hear how things are working out.

Sources:

(1) Rupert Hebblethwaite, ‘The Municipal Housing Programme in Sheffield before 1914’, Architectural History, Vol. 30, (1987). Much of the historical detail and some of the quotes which follow also come from this source.

(2) Official Illustrated Catalogue, Yorkshire and North Midland Cottage Exhibition, quoted by Picture Sheffield.

(3) Patrick Abercrombie, ‘Modern Town Planning in England: A Comparative Review of “Garden City” Schemes in England’, The Town Planning Review, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Apr., 1910)

(4) Sheffield Forum, Flower Estate, what went on?

(5) Flower Neighbourhood Profile, 2005/06

(6) From the Flower Estate Community Association History. You’ll find much more about the Association’s hard work and struggles over the years here.

(7) Wincobank Estate Arts Project 2008, press release, October 2008

A special thank you to Picture Sheffield for allowing use of the historic image above.

More information and illustrations can be found on the Looking at Buildings pages on the Estate.