Tags

Last week’s post looked at some of the contextual forces behind Birmingham’s post-war volte-face – from a city proclaiming a ‘prejudice against flats’ as ‘one expression of its independence of character’ to one which led the country in building big and high. Today, we’ll examine the internal dynamics – a potent combination of ideals, money and power – which brought this love affair with high-rise to its peak and ensured that it would all ultimately end in tears.

The Sentinels, Holloway Head, built by Bryants between 1971-72. Birmingham’s highest blocks at 32 storeys, they were intended to surpass the recently completed Red Road flats in Glasgow © Oosoom and made available by Wikimedia Commons

Birmingham had been home to some of the ‘big beasts’ of local government since the days of Joseph Chamberlain. That tradition continued. Labour had won control of the Council in 1945 but a Unionist (Conservative) administration, highly critical of the inadequacy of its council house building record, was returned to power in 1949. A House Building Committee was set up under the chairmanship of the civil engineering contractor, Sir Charles Burman.

Burman, according to Patrick Dunleavy, ran a ‘one-man show’, excluding councillors linked to building trades unions or private house-builders, preferring to build close relations with the large construction firms such as Laing, Wimpey and Wates. (1)

In a generally more favourable climate, housing completions increased rapidly, reaching an early peak of 4800 in 1952 when already 20 per cent of completed homes were flats. That success notwithstanding, Labour returned to power in the same year; its housing supremo, Alderman Albert Bradbeer complaining that Birmingham would soon be surrounded by a ‘ring of forts’. (2)

Labour appointed a City Architect in 1952, AG Sheppard Fidler (formerly the Chief Architect of Crawley New Town), with the apparent intention of improving the design and planning credentials of its house-building programme. But Sheppard Fidler was condemned to work under Herbert Manzoni’s powerful Public Works Department for the first two years of his tenure and had to fight for influence thereafter. He recalled: (3)

Labour appointed a City Architect in 1952, AG Sheppard Fidler (formerly the Chief Architect of Crawley New Town), with the apparent intention of improving the design and planning credentials of its house-building programme. But Sheppard Fidler was condemned to work under Herbert Manzoni’s powerful Public Works Department for the first two years of his tenure and had to fight for influence thereafter. He recalled: (3)

When I went to Birmingham, you could have called it Wimpey Town or Wates Town. The Deputy City Engineer came into my office the very first day I arrived, shoved all these plans on my desk, and said ‘Carry on with these! ‘ He was letting contracts as fast as he could go, didn’t know what he was doing, just putting up as many Wimpey Y-shaped blocks as he could! This rather shattered me, because we’d had very careful schemes prepared at Crawley, with very great interest on the part of the Development Corporation, whereas in Birmingham the House Building Committee could hardly care about the design as long as the numbers were kept up – I’d been used to gentle Southern people!

Burman, for his part, described the City Architect as:

a very nice chap, but he was a perfectionist – he liked to get things just so. This meant that he did not push the housing programme along as quickly as he might have done, because building and planning well and carefully was more important to him than building a lot of houses.

The lack of self-consciousness in that last statement can speak for itself.

Sheppard Fidler’s stock was not helped by the sharp fall in council completions in the early sixties and the frustration caused thereby to the latest of the Council’s big beasts – nicknamed the ‘little Caesar of Birmingham’ or sometimes just ‘the boss’ – Labour councillor Harry Watton.

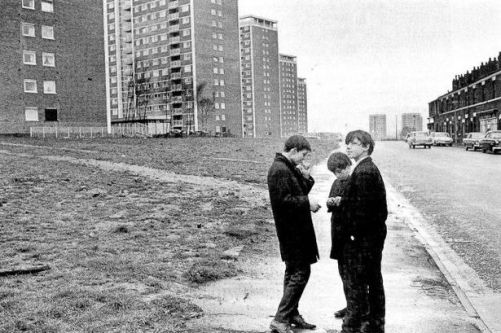

Richard Crossman, Minister of Housing and Local Government, and Harry Watton (to the right). Druids Heath, 1965. Crossman’s presence is an indication of the high-level government support for Birmingham’s Industrialised Building drive.

Watton’s patience, already stretched by Sheppard Fidler’s carefully contrived mixed development schemes, apparently broke when the latter proposed using the French firm Camus to build the Castle Bromwich estate. Against the City Architect’s opposition, Watton redirected almost all the high-rise building programme to local firm, C. Bryant & Son.

By now, we are talking of Industrialised or System-building. Conservative and Labour governments competed in a political arms race to build the most homes – the Conservatives pledged 350,000 a year in 1963 only to be outbid by Labour’s 400,000. The means was system-building: the Conservatives had expected 25 per cent of new dwellings to be constructed by this method; the new Labour government raised the figure to 40 per cent. Councils which ‘seemed to be co-operating were “rewarded” in terms of enhanced capital allocations, speeding approvals, etc.’ (4). Industrialised building seemed not only the inevitable means to achieve housing goals but a modern and progressive one too.

In 1963, the first Bison Wallframe blocks were completed in Kidderminster with Minister of Housing and Local Government Keith Joseph present at their opening. A group of Birmingham councillors visited too. As one member of the party recalls:

the way to the blocks was through this great marquee – which was loaded with drink and, er, food…So we stayed there quite a long time and then we went out and looked at the flats. Well by this time they could have been inlaid with gold! In fact they looked pretty awful from the outside – they had this grey and white panelling. Inside they were all right…

As they left, it was decided, ‘”Right, we’ll take five blocks.” Just as if we were buying bags of sweets.’ In fact, the Council went on to place a contract for 12 standard plan 11-storey Bryant-Bison blocks. Sheppard Fidler was told to find sites for them.

He resigned the following year, concluding ruefully that Birmingham was ‘an engineering city’ which ‘felt it didn’t need a City Architect’. He was briefly succeeded by former Leeds City Architect, J R Sheridan Shedden who, in an all-out dedication to the goal of raising output, reorganised his department into effectively a large contractor’s design team. One sensitive ex-LCC architect concluded:

That was an appalling mediaeval baron of an architect, a man of zero architectural quality, a primeval creature who could have gone to work for Wimpey or some other contractor – he could have been a Soviet general, with a huge hat and a coat buttoned up to his chin!

But Sheridan Shedden achieved results. Completions climbed to 4728 in 1966 and peaked the following year at 9023 (proportionately three times the figure for the whole of London). The City Architect himself had died prematurely one year earlier but, if that gave his critic any comfort, it was surely rapidly dissipated by the new head of department, Alan Maudsley.

First some background: between 1966 and 1968 Bryants had won 66 per cent of all Birmingham’s high-rise contracts. The fact that its public relations were handled by former councillor and local Labour MP, Dennis Howell, and that Labour alderman WT Bowen was one of the firm’s directors was, of course, coincidental; Bryants’ 2000-strong Christmas gift list merely a sign of the company’s festive spirit.

But Maudsley’s guilty plea in a 1975 High Court case alleging a corrupt relationship with a local architectural practice and the subsequent imprisonment of Bryants’ managing director and two directors, charged with providing gifts to various West Midland councillors, are a matter of record. Allegations were also made of money paid by Bryants to Maudsley.

More anecdotally, Private Eye tells the story of a topping-out ceremony for a Bryants’ scheme performed, at Dennis Howell’s request, by a somewhat tired and emotional George Brown. ‘Brown ‘waved an all-embracing hand over the assembled dignitaries saying “You’re all in Chris Bryant’s pocket” before unsteadily despatching the last shovelful of concrete’. (5)

This was not local government’s finest hour and there’s no need to sugar-coat the corruption here. Glendinning and Muthesius are kind to Maudsley, however, noting his ‘dynamism’ and the impressive cost-consciousness of Birmingham’s building programme under his stewardship. They quote an official from Bryants stating: ‘he’d tell the councillors what to do…while we’d end up doing jobs at his behest and his price!’.

These were, in all honesty, febrile times for local government as the idealism of the slum clearance and rehousing programmes collided with the more questionable dynamics of municipal ambition and personal power. Add to that the reliance on system-building (and we haven’t even examined the practical problems of that – see next week’s post) and an oligopoly of major contractors and you get a very toxic mix indeed.

Still, William Reed, Maudsley’s deputy and successor, offers a perspective we would do well to remember: (6)

It was exciting to be part of that particular period. There may have been things going on in the background – graft and so on – but they weren’t the things at the top of people’s minds. What was in people’s thoughts was – ‘For God’s sake get on and build those houses, and get these people out of the slums!’

Sources

(1) Patrick Dunleavy, The Politics of Mass Housing in Britain, 1945-1975. A Study of Corporate Power and Professional Influence in the Welfare State (1981)

(2) Phil Ian Jones, ‘The Suburban High-Rise Flat in the Post-War Reconstruction of Birmingham, 1945-1971’, Urban History, Vol 32, Part 2, August 2005

(3) This and the following quotations are drawn from Miles Glendinning and Stefan Muthesius, Tower Block – Modern Public Housing in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland (1994)

(4) Association of Metropolitan Authorities, ‘Defects in Housing Part 2: Industrialised and System Built Dwellings of the 1960s and 1970s’ (1984)

(5) ‘Sharpesville’, Private Eye, 12 July 1974, quoted in Phil Ian Jones, ‘The Rise and Fall of The Multi-Storey Ideal: Public Sector High-Rise Housing in Britain 1945-2002, with Special Reference to Birmingham’, PhD thesis, School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Birmingham, 2003

(6) Quoted in Glendinning and Muthesius, Tower Block

The collection of 446 photographs of the late Phyllis Nicklin, a tutor in Geography at the University of Birmingham, has been made available under the Creative Commons licence.