This is an unashamed plug. Collage, the picture archive managed by the London Metropolitan Archives, has always been a wonderful resource. The good news is, it just got better. The new website is more user-friendly and includes added features – a geo-tagged location map and, using newly digitised content, a zoom function allowing you to get to the finer detail. You’ll find some short film clips too for the first time.

The sheer numbers testify to the breadth of the collection – over 250,000 photographs, prints and drawings, over 1000 maps, plus some 6000 images of paintings, watercolours, drawings and sculptures from the Guildhall Art Gallery collection.

Most are London-related in some shape or form but, if that sounds too narrow for readers beyond the capital, they’re worth another look. The collection provides a social history of much wider relevance – covering schooling, the workhouse, pubs and popular entertainment, religious observance…basically, you’ll likely find something of interest whatever your focus. Use the map to search your neighbourhood if you have a local interest, use the search box to look up specifics, or just browse – the list of subject tags covers an enormous range of topics

Since this blog is principally about council housing, that’s going to be my particular focus here and, since there were 769,996 council homes in Greater London by 1981, there is, as you can imagine, plenty to see. The tag ‘Housing estates LCC/GLC’ throws up over 17,000 images. That’s practically a lost weekend for me!

‘Andover: children playing on a housing estate’ (1973) (c) Collage, London Metropolitan Archives

To prove the point about looking beyond London, let’s begin by using ‘New and expanding towns’ as a search term – from Andover to Wellingborough, you’ll find over 5500 images of the London County Council and Greater London Council’s post-war overspill programme.

‘Wellingborough: interior of a new build property’ (1971) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

The particular strength of the collection is the variety of images and moments captured. There are plenty of photographs of the high-quality housing that London was proud to build for its displaced population, of course, but factories, shopping centres, playgrounds and schools, and interior images feature too – the latter providing an insight into the lived lives so rarely captured in the architectural record.

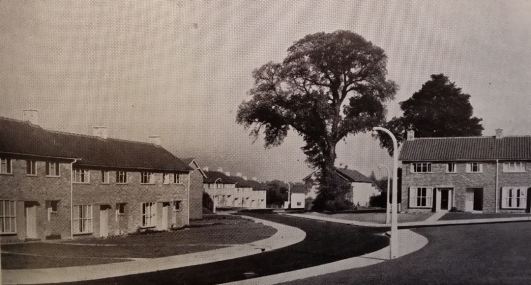

‘General view of the Britwell Estate’ (1964) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

Or look up the Britwell Estate in Slough, home to Alan Johnson when our former Home Secretary was just a jobbing postman and fondly remembered by him as ‘Arcadian’. (1) Or Sheerwater, or Harold Hill. These are just three of the thirteen out-of-county estates (with 45,500 homes in all) built by the LCC before its abolition in 1965. A strength of many of these images is that they are not striving for architectural effect.

‘Sheerwater Estate: shopping centre (1960) – anchored by the Co-op as was typical (c) London Metropolitan Archives

‘Boundary Estate: Arnold Circus’ (1966) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

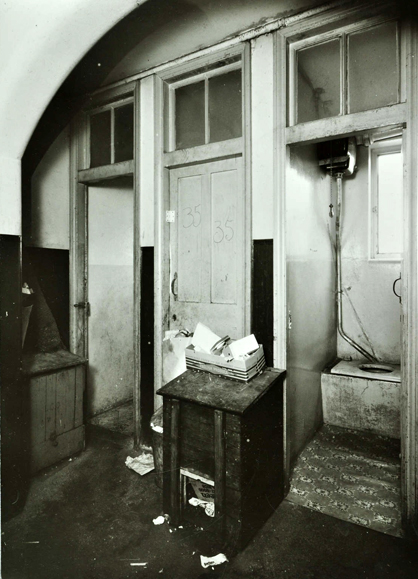

But for anyone seeking an architectural record of housing history, the archive does, of course, provide a wonderful record. There are 228 photographs of the Boundary Estate in Bethnal Green, the LCC’s very first housing estate, opened in 1900. There are fine external shots of the dignified and attractive housing the Council provided but later photographs too showing unmodernised interiors, reminding us just how basic this early municipal housing was. (Look up ‘slums’ and you’ll have another reminder; this time that council housing was, almost without exception, immeasurably superior to the working-class housing which preceded it.)

‘Boundary Estate: old lavatory’ (1959) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

Moving on to the interwar period, you’ll see some of the LCC’s major schemes, for example, the Becontree, Watling and Downham Estates – three of the so-called ‘cottage estates’ which provided just over half of the 89,000 homes built by the Council in the 1920s and 1930s. For all the criticisms of their suburbanism, the images testify to the quality and essential decency of these new homes.

‘Watling Estate: 1 Dean Walk’ (1931) – obviously proud winners of the LCC’s competition for best-kept gardens (c) London Metropolitan Archives

Meanwhile, in the inner city, walk-up, balcony-access, five-storey blocks provided the bulk of the Council’s new build. The Honor Oak Estate in Lewisham was typical.

Honor Oak Estate, Cayley Close: residential tenements’ (1966) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

The Ossulton Estate in St Pancras, completed in 1931, was a rare LCC foray into more modernist design though its innovative exterior concealed a more conventional tenement block form. Rather charmingly, a number of these photos cover refuse disposal. Such is the unglamorous nitty-gritty of local government service.

‘Ossulston Estate: woman entering rubbish into a chute’ (1936) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

In the post-Second World War period, 162 images celebrate the ‘before and after’ of the Lansbury Estate and the thoughtful planning which went into it. Here was a portent of the emerging, more democratic world to which the nation aspired and, though it too was criticised by some architectural critics of the day as too modestly suburban, its housing looks as attractive and neighbourly as its architects intended.

‘Brandon Estate: Warham Street looking west to estate’ (1962) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

‘Pepys Estate: construction work progress’ (1966) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

With the later emergence of high-rise and mixed development schemes, though, there was more scope for architectural daring. The archive provides a superb record of the planning, construction and opening of the Brandon Estate in Southwark and the Pepys Estate in Deptford, for example.

‘Alton Estate: aerial view’ (1964) – Alton East in the far background, Alton West in the foreground (c) London Metropolitan Archives

Let’s conclude by focusing on one estate I’ve never quite summoned up the courage to write about in detail yet – the Alton Estate in Roehampton, described by a contemporary American commentator as ‘probably the finest low-cost housing development in the world’. (2) Alton East, the earlier half of the Estate, constructed between 1952 and 1955, retained a Lansbury-esque ‘picturesque informality’ in Pevsner’s words, reflecting the New Humanist, Scandinavian influences which inspired its design team. (3) Alton West was more uncompromisingly modernist in aesthetic – Brutalist as the newly-coined term would have it – and took its inspiration from Le Corbusier.

‘Alton Estate, Roehampton Lane: artist’s impression’ (ND) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

‘Alton Estate, Hyacinth Road: architectural model’ (1965) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

‘Alton Estate, Hyacinth Road: architectural plan’ (1967) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

That detail is elsewhere or for another time but browse the archive and you’ll find the artists’ impressions and plans and a range of images which capture the excitement and hope – and careful design – which underlay the new scheme. You’ll see clubrooms too and an old people’s day centre, children playing in generous open space – a testament to the community being built – and, above all, interior shots of the living rooms, kitchens and bedrooms which made this Estate, like so many others, a good home to its new residents.

Alton Estate: architectural model of interior of flat (1957) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

’22 Hinstead Gardens, Alton Estate, living room’ (1960) (c) London Metropolitan Archives

All this has barely scratched the surface but I hope it’s whetted your appetite. Local history libraries and archive services across the country provide a wonderful resource whether you’re researching a family or local history or something more academic. We must cherish and – in this time of cuts – defend them. My thanks to the London Metropolitan Archives for providing this fantastic on-line resource. Do check it out.

You’ll find Collage at http://collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk/

Sources

My thanks to the London Metropolitan Archives for supplying and allowing use of the images used in this post.

(1) Alan Johnson, Please, Mr Postman (2015)

(2) GE Kidder Smith, The New Architecture of Europe, an Illustrated Guidebook and Appraisal (Meridian Books, Cleveland and New York, 1961), p42

(3) Bridget Cherry, Nikolaus Pevsner, London 2: South (Yale University Press, 2002) p689

I am most anxious that the planning should be such that different income groups living in the new towns will not be segregated. No doubt they may enjoy common recreational facilities, and take part in amateur theatricals or each play their part in a health centre or a community centre. But when they leave to go home I do not want the better off people to go to the right, and the less well-off to go to the left. I want them to ask each other ‘are you going my way?’

I am most anxious that the planning should be such that different income groups living in the new towns will not be segregated. No doubt they may enjoy common recreational facilities, and take part in amateur theatricals or each play their part in a health centre or a community centre. But when they leave to go home I do not want the better off people to go to the right, and the less well-off to go to the left. I want them to ask each other ‘are you going my way?’

I did not find people pleading and crying that they would be turned out of their shops, theirs houses and farms, but a great mass of people who looked forward to the day when a new town would arise in this very ill-served town educationally, culturally and industrially…

I did not find people pleading and crying that they would be turned out of their shops, theirs houses and farms, but a great mass of people who looked forward to the day when a new town would arise in this very ill-served town educationally, culturally and industrially…

But Harlow’s presiding genius, almost a City Father in the truest sense of the term, was Frederick Gibberd. Gibberd is perhaps a slightly overlooked figure now – a member of the Modern Architecture Research (MARS) Group in the 1930s but disdained by some of his erstwhile modernist colleagues for his wholehearted embrace of the Scandinavian-inspired New Humanist style which – through his influence – held dominant sway in this immediate post-war period (manifest in his work in the

But Harlow’s presiding genius, almost a City Father in the truest sense of the term, was Frederick Gibberd. Gibberd is perhaps a slightly overlooked figure now – a member of the Modern Architecture Research (MARS) Group in the 1930s but disdained by some of his erstwhile modernist colleagues for his wholehearted embrace of the Scandinavian-inspired New Humanist style which – through his influence – held dominant sway in this immediate post-war period (manifest in his work in the

Every possible use must be made of existing buildings, villages, trees and place-names to give a feeling of continuity with the past…I remembered my own youth in Coventry and Birmingham where it was a whole day’s excursion to get to the country…I didn’t want any of these children to grow up without having seen a cow.

Every possible use must be made of existing buildings, villages, trees and place-names to give a feeling of continuity with the past…I remembered my own youth in Coventry and Birmingham where it was a whole day’s excursion to get to the country…I didn’t want any of these children to grow up without having seen a cow.