Tags

1950s, 1960s, LCC, Westminster

There are plenty of things that make the Churchill Gardens Estate in Westminster a bit special. In 2000 the Civic Trust voted it the outstanding building scheme of the last forty years. When it was built it was the largest urban area to be built to the plans of a single firm of architects. But let’s begin with its founding inspiration.

Churchill Gardens – the Pimlico Housing Scheme as it was originally designated – was the only major project within the visionary Abercrombie Plan for the post-war reconstruction of London to be completed. Its scale – a 30 acre site, 1661 homes, 36 blocks, a population of some 5000 – and its design give some indication of the ambition of post-war hopes.

Charles Latham, then leader of the London County Council, acknowledged the Plan would ‘certainly cost a great deal’: (1)

but not more than unplanned building and a lot less than war. In a way, you know, this is London’s war, against decay and dirt and inefficiency. In the long run, plans such as this are the cheapest way to fight those enemies. What a grand opportunity it is. If we miss this chance to rebuild London, we shall have missed one of the great moments of history and shown ourselves unworthy of our victory.

In the event, London grew in a typically unfashioned way and we might not, on balance, regret that but we should lament at least the loss of those dreams of a humane environment, community living and decent homes for all.

Churchill Gardens stands as a worthy reminder of those dreams. It was built – another indication of the world we have lost – by a Conservative local authority, Westminster City Council.

The site was an area of decayed terraces which had been scheduled for redevelopment in the 1930s. Hitler’s bombs added their own urgency to rebuilding and, in their way, an opportunity for design on a grand scale.

Westminster organised a competition for the scheme which attracted 64 entries. It was won by two recent graduates from the Architectural Association, Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya, then aged just 24 and 25 respectively. They were influenced, it is said, by the Dutch housing projects of the 1930s and the Weissenhofsiedlung workers’ housing scheme of 1927 in Stuttgart. (2)

What is striking to any visitor to the Estate is – despite its size – its intimacy and humanity. Powell himself described his ‘mistrust of conscious struggling after originality…of the monumental approach’. And it seems clear that the Estate has worked – it has prospered as a decent place to live even as many other, superficially more grandiose post-war housing schemes have failed.

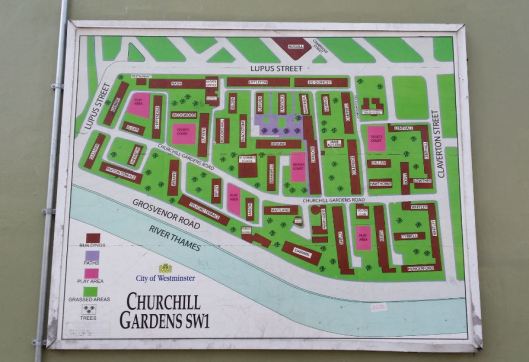

In bare descriptive terms, Churchill Gardens comprises a series of nine to eleven-storey slab blocks interspersed by smaller blocks of three to five-storeys. A seven-storey block, with ground floor shops, encloses the Estate along its Lupus Street frontage. Two terraces of three-storey town houses run along the Thames-side Grosvenor Road front of the Estate.

It was a mixed development which embodied post-war planning ideals both structurally – in its range of building forms – and sociologically. The Estate was intended to accommodate a balanced cross-section of society. In this, it reflected the principles of Labour’s 1949 Housing Act which had removed the stipulation that council housing cater only for the working class and captures post-war visions of a classless society.

The taller blocks follow the Zeilenbau arrangement developed by Bauhaus architects in the 1920s – set in a parallel north-south axis, perpendicular to the river, which maximises the sunlight each home receives.

But the overall layout escapes any rigidity or that monumentalism that Powell decried. Its main road curves through the Estate, placing the main blocks slightly irregularly, and the overall configuration creates a series of open spaces, courtyards and play areas which provide a human scale. (3)

Naturally, the housing blocks get most attention but the landscaping, also personally designed by Powell and Moya, deserves recognition too. It’s disarmingly simple – Powell recalls they worked with a former head gardener at Kew ‘who was sufficiently diffident not to put a herbaceous border everywhere’. Elain Harwood describes ‘small quadrangles with neat hedges or foot-high railings … careful patterns of paving and grass, which felt natural to the clients and themselves’. (4)

The first four blocks completed towards the eastern edge of the Estate – Chaucer, Coleridge, Keats and Shelley Houses – in 1950 won Festival of Britain Architectural Awards. Their concrete cross frame construction is offset by an applied brick facing and the eye-catching full-height, glazed staircases provide a vertical line to break up their horizontal mass.

In the second phase, staircases were replaced by gallery access which allowed a larger number of smaller flats and larger windows. The ‘piloti’ (stilts) on which the central blocks are raised gives a greater sense of openness to the overall design while ‘the subdivision and extent of glazing means many of the large blocks retain a delicate appearance, some with an almost translucent quality’. (5)

The final phase, back towards the east, facing Claverton Street, completed in the early sixties, reflects the changed architectural ethos of its time. The five-storey block which bridges Churchill Gardens Road with its facing of white glazed brick echoes the stuccoed nineteenth-century terraces opposite and joins the Estate as a whole with its surrounding townscape.

The detail comes from Westminster City Council’s conservation audit. The Estate was designated a conservation area in 1990. reflecting the earlier recognition it had received – two Civic Trust awards in 1962 (one for building, one for landscaping) – and that which was to come. Six blocks were Grade II listed in 1998.

An early photo of the Estate showing the accumulator tower with Battersea Power Station in the background

So was the glazed accumulator tower – designed once more by Powell and Moya – which marks Britain’s first district heating system. Initially, it collected surplus heat from Battersea Power Station via a tunnel under the Thames. Battersea Power Station closed in 1980 and since 2006 heat has been supplied by the boilers in the Estate’s own pump house. To Ian Nairn, the architecture of the heating system was the highpoint of the Estate: (6)

The best single building is the crisp and elegant boiler house at the bottom of the big polygonal tower…the machines and their fine-drawn glass and steel cage which surrounds them are a perfect match.

Of course, ultimately – whatever the architectural accolades – the Estate must stand or fall as a place to live, as a home. And, in this, it seems to have served well. For one resident, who moved in in 1952, ‘it was like moving into heaven’. For another, who moved there as a child in 1963, it:

seemed endless and full of variety; a couple of pubs, the huge water tower, playgrounds, lots of green, the view of Battersea Power Station across the Thames. There was a school, the social club, the adjacent bombsite. There was nothing like it anywhere else in London.

Residents in the elite Dolphin Square flats nearby complained, facing a rent rise in 1962, that ‘many of the flats are not as nice as those put up by the Council in Churchill Gardens opposite’. (7)

Nowadays about half the Estate’s homes have been purchased under Right to Buy. Flats sold for as little as £13,500 now sell for much, much more – one agent is currently listing a two-bed flat on the estate at £535,000. Or as one writer puts it (with an offensiveness to be expected from a property writer for the Daily Telegraph perhaps but with a surprising blindness to the real quality of Churchill Gardens): (8)

nowadays high-end estate agents visit Churchill Gardens more often than police officers…String vests and hole-ridden socks once dangled from balconies; now, it’s petunias and clematis. Yuppies have replaced the old municipal lino and Formica fittings with high-design interiors, a bit like putting a Porsche engine into a Vauxhall Viva.

In fact, the Estate has paradoxically – though in ways very far from those imagined in the heady days of post-war social democracy – become a mixed community…but not a classless one.

Managed by City West Homes since 2002, it suffers from problems that you would expect to find in any inner-city estate which still, disproportionately, houses some of the least well-off in our society. There are complaints about drug-dealing, dangerous dogs and antisocial behaviour. One of its two pubs now stands derelict. (9)

But in general residents like the Estate – they experience it as a friendly and safe community and a pleasant place to live. The words of Westminster’s planners ring true:

Today it remains a testament to the optimism and spirit of renewal which characterised the post-war period and the belief in the possibility of provision of higher standards of housing for all.

That should be a call to action, not an epitaph.

Sources

(1) Interviewed in The Proud City: a Plan for London (1946)

(2) Philip Powell, Dictionary of National Biography

(3) Christine Hui Lan Manley, Churchill Gardens, Pimlico, Twentieth Century Society Building of the Month, August 2013

(4) Elain Harwood, ‘Post-War Landscape and Public Housing’, Garden History, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Summer, 2000)

(5) City of Westminster, Churchill Gardens Conservation Area Audit (ND)

(6) For details and images, see the Pimlico District Heating Undertaking page on the 28DL Urban Exploration forum. The quotation from Ian Nairn is in the English Heritage listing

(7) Quotations from Giles Worsley, ‘Estate of grace’, Daily Telegraph, 25 March 2000, ‘Churchill Gardens, London – Living the high life’, The Independent, 13 February 2000 and ‘Rent Shock for Tenants’, The Times, April 30, 1962 respectively

(8) Catherine Moye, ‘Square deal that turned sour for the well-to-do’, Daily Telegraph, 5 July 2003.

(9) Residents’ complaints are taken from City of Westminster, Churchill War Profile (July 2012) – Churchill Ward also contains the Ebury Bridge Estate as well as areas of private housing – and Churchill Gardens News, April 2014

I worked on a neighbouring estate, Lillington Gardens, in the 1980s and always felt that the pair of them were amongst the best flatted council estates that I had seen; both seem to have stood the test of time well I suspect that it was because there seemed to be a good attention to detail and both seemed to be well maintained. A really interesting post, as always.

Thanks. I agree about the estates. I took at look at Lillington Gardens when I was in the area and it still has a good ‘feel’ about it.

Reblogged this on Old School Garden.

The internal design of the flats is also excellent – great hot cupboards and lots of storage space, big windows and balconies! And the trees around the site are glorious.

Thanks for commenting. I only got to see the outside – and the glorious trees – so it’s good to hear that the flats are nice too.

Pingback: Social Housing under Threat: Keep it ‘affordable, flourishing and fair’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Lillington Gardens Estate, Westminster: ‘civilizing, elegant and exciting’ | Municipal Dreams

Very interesting to read. Glad you took the pictures when the sky was blue – makes such a difference! The picture you have displayed of Chaucer House is incorrect. I think it might be Bramwell House. I lived in Churchill Gardens from 1951 to 1971

Thanks for your comment,Collette. I’ll check out that pic of Chaucer House and correct as necessary.

Can I just back up Collette there, I grew up on the estate and lived there from 1967 to 1987. That is definitely Bramwell House, the area in-front had a playground and a football pitch behind the bushes and trees that you can see in the photo. The large block in the picture that’s captioned “mixed-development” is Chaucer House. This was opposite Bramwell house to the east.

Thanks to both of you for that – I’ve made the correction.

I left in 1978 and when I look back I had a fantastic childhood living there. The open play areas were amazing for central London and no surrounding estates had the same facilities that we enjoyed. Internally the flats were relatively small but back then people had less possessions. I can still remember the first family to get a colour TV!

How times have changed.

Excellent article! I relish reading anything about Churchill Gardens which was my home from 1964 – 1993, my parents subsequently ‘sold up’ and retired in 2000. Luckily I am still in Pimlico but what I wouldn’t give to be back living there now… with a Lift and Balcony! The flats have always had a Modern feel, and I was astonished to discover in later life that they started building them in ’51 or there abouts! After all said and done, with the recent bad publicity and rumours of undesirable tenants – I believe it could be like the proverbial Pheonix and rise again. I sincerely hope so!

Pingback: Council Housing in Winchelsea: ‘the working class are not wanted on the hill’ | Municipal Dreams

Help us Save St. George’s Square and Pimlico Gardens from Lambeth and Wandsworth Councils.

http://5fields.org/317/nine-elms-pimlico-bridge-summary/

https://m.facebook.com/pages/SOS-Save-Our-Square/942741705799657

https://www.change.org/p/boris-johnson-stop-the-planning-and-construction-of-the-proposed-nine-elms-to-pimlico-bridge-and-the-unnecessary-expenditure-of-43-million-pounds-on-this-project-this-money-can-be-put-to-better-use

Pingback: Open House London: A Tour of the Capital’s Council Housing, Part One | Municipal Dreams

absolute nightmare

I was Born in Gifford House in 1962 .. Only lived there for 5 years but remember the playgrounds which were great fun but basically death traps !

Pingback: Harlow New Town: ‘Too good to be true’? | Municipal Dreams

It’s a shame the previous homes was demolished and now replaced by rubbish 1950’/60’s design!!!

Take a look at how it was before!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Hı

Do you have an olde photos for this area before these building ?!

Your best bet is to look through the London Collage photo archive: https://collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk/london-picture-map?WINID=1489651436773#51.488207721830896%2F-0.13859876986691333%2F16%2FRoadMap%2F-1

Me and my parents moved into Chaucer House in 1953. We transfered to Gilbert House in 1962 and finally moved off the estate in 1967. My Dads 4 sisters and their families also lived on the Estate as more blocks were built (Lutyens & Wilkins). It was a great place to grow up. Modern flats, endless hot water, central heating, we felt quite privileged. As nearly everyone had moved from the old terraced houses, there was still that community spirit. Neighbours looked out for neighbours, and for us children it was a safe and caring community.

Great reading

The picture is not Telford Terrace but is Paxton Terrace showing the back of Sullivan House in the background

Thanks for your comment. You’re right about that caption and I’ve corrected it.

Pingback: Community Fibre gets £25m to fund broadband in London | TECH and Global NEWS

Pingback: Community Fibre gets £25m to fund broadband in London – Satyajit

Pingback: Let's hear it for the Jammie Dodgers ponds! Everyday marvels win protection | NewsColony

Pingback: Let's hear it for the Jammie Dodgers ponds! Everyday marvels win protection | Architecture - The Trend Public: Breaking News, India News, Sports News and Live Updates

Pingback: Let's hear it for the Jammie Dodgers ponds! Everyday marvels win protection – CityInsidernews

Pingback: Let's hear it for the Jammie Dodgers ponds! Everyday marvels win protection – 6 News Today

Pingback: Let's hear it for the Jammie Dodgers ponds! Everyday marvels win protection | Art and design - News 4 You

Pingback: Let's hear it for the Jammie Dodgers ponds! Everyday marvels win protection | Architecture | Far World News

Pingback: Let's hear it for the Jammie Dodgers ponds! Everyday marvels win protection - U.S.A Top News

Pingback: Twelve Trees that Defined my Lockdown – Part 2 – The Street Tree

Pingback: Great estates: the changing role of trees in the municipal housing landscape | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Penthouses and poor doors: how Europe's 'biggest regeneration project' fell flat | Art and design - Luxury Lifestyle

Pingback: Penthouses and poor doors: how Europe's 'biggest regeneration project' fell flat | Architecture - ClassyBuzz

Pingback: Penthouses and poor doors: how Europe’s ‘biggest regeneration project’ fell flat – Financial News

Pingback: Penthouses and poor doors: how Europe's 'biggest regeneration project' fell flat - Pehal News

Pingback: Penthouses and poor doors: how Europe's 'biggest regeneration project' fell flat | Architecture - cramzine

Pingback: Penthouses and poor doors: how Europe's 'biggest regeneration project' fell flat | Architecture | StarsPressNews.com

Pingback: London’s Modernist Maisonettes: ‘Going Upstairs to Bed’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Grosvenor Estate, Page Street – Streetscapes

Great article, great photos. I grew up in Churchill House: the estate still features in my dreams from time to time.

Oops, I meant “Whitley House”.

By the way, Calverton Street should read Claverton. :-)

Tha k you for your comment and pointing out my mistake – it’s corrected now.

Pingback: Ten Years of Municipal Dreams | Municipal Dreams

Exactly 75 years ago this January, I moved into a rented Ground floor Flat at 9 Lupus Street straight from birth at Westminster Hospital. We moved out to North London in May 1966 as the site was needed for Pimlico School. I have wonderful memories of growing up in Pimlico including Churchill Gardens and Dolphin Square. In recent months I have been sharing memories on a facebook Pimlico site. Thank you for publishing all this here.. Very enjoyable ERIC ELIAS