Last week’s post looked at the genesis of Red Vienna’s stupendous interwar housing programme. In this, we’ll examine and assess its built accomplishments and address its tragic conclusion. With almost 62,000 new flats constructed in some 348 schemes, there’s a lot to cover but here I’ll take you on a virtual tour of some of the estates I got to see in person when I visited the city earlier this year. Conveniently, they also offer a roughly chronological overview.

Metzleinstaler-Hof

Vienna’s first Gemeindebau (municipal tenement block) of the new era and in many ways the model for what followed was Metzleinstaler-Hof on Margaretengürtel, about 2.5 miles south-east of the city centre, completed in extended form in 1925.

It would help form what some called the Ringstrasse des Proletariats – a deliberate echo of and challenge to the monumental Ringstrasse (literally a ring road but more a grand boulevard) created around Vienna’s inner core under Hapsburg rule.

It would help form what some called the Ringstrasse des Proletariats – a deliberate echo of and challenge to the monumental Ringstrasse (literally a ring road but more a grand boulevard) created around Vienna’s inner core under Hapsburg rule.

Herbert Gessner

The chief architect of Metzleinstaler-Hof was Herbert Gessner. Gessner, though trained by leading imperial architect Otto Wagner at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in the 1890s (as were the majority of his colleagues) was a more ‘political’ architect than some, moving in Social Democratic circles and undertaking work for the Austrian labour movement before the First World War. He became a trusted leading figure for many of Red Vienna’s housing schemes of the 1920s.

At Metzleinstaler-Hof, a potentially austere exterior is enlivened by decorative detail and bay windows; a quiet inner courtyard is less obvious and accessible than would be the case in later schemes. Its 250 flats are tiny but the scheme’s essential breakthrough was the inclusion of a bathhouse, laundry, library and nursery – a clear indication of the communal facilities that would be the hallmark of the Social Democratic housing programme.

Matteotti-Hof @ Wikimedia Commons

Matteotti-Hof (named after the Italian socialist murdered by fascists in 1924) – a 423 apartment block designed by Heinrich Schmid and Hermann Aichinger and completed in 1927, lies to the rear.

Reumann-Hof

Back on Margaretengürtel, Reumann-Hof, another Gessner design completed in 1926, lies immediately to the north. It’s a larger and more grandiose scheme reaching eight storeys (more were planned but financial constraints intervened), comprising 392 apartments and 19 shops. To the side of its grand façade, set back from the street, majolica-tiled entrances lead to green, shaded courtyards.

No. 4 Karl-Löwe-Gasse

A ten-minute walk to the east gets you to one of the largest complexes of social housing in Vienna, either side of Längenfeldgasse. On the way, you might pass no. 4 Karl-Löwe-Gasse. It’s a small 1930 scheme of 18 apartments designed by Anton Potyka – not a showpiece but just one of the hundreds of such blocks built by the municipality at this time.

Reismann-Hof

Reismann-Hof, just beyond, is, by contrast, one of the Red Vienna’s eight ‘superblocks’, comprising 623 apartments, officially opened in 1925. The scheme was originally named Am Fuchsenfeld but was dedicated after the Second World War to the memory of Edmund Reismann, a Social Democratic politician murdered in Auschwitz in 1942.

Fuchsenfeld-Hof

Its architects Heinrich Schmid and Hermann Aichinger also designed Fuchsenfeld-Hof just across the road and built at around the same time. The scheme is celebrated for its series of landscaped courtyards and, in its heyday, a children’s paddling pool now converted to a playground.

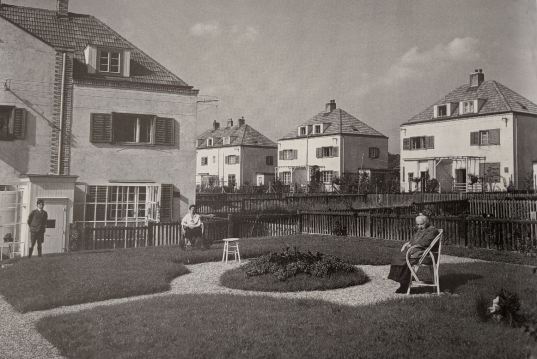

George Washington-Hof

If you’re following me geographically, it’s a brisk fifteen-minute walk to the south to get to George Washington-Hof – another of the ‘superblocks’ with some 1084 apartments. It’s an unusually extensive scheme too, reflecting the struggle around its design between those advocating a ‘garden city’ style and those a more urban tenement design. The relatively low-rise design and extensive, attractive landscaping offered a compromise somewhere between the two. If you look closely around the complex, you’ll see a contrast between the work of the two architects involved: Karl Krist’s plain façades and the more decorative pebble-clad façades, glazed verandas and pointed-gabled staircases of Robert Örley.

From here, there’s no direct route to Karl-Marx-Hof in the north but a trip on the tram to Karlsplatz and a rail journey from there to Heiligenstadt station takes around forty minutes and will give you an idea of the transport infrastructure that was vital to the Social Democrats’ urban programme. Karl Marx-Hof itself – or some of it as it’s pretty big (four tram stops from end to end to keep the transport focus going) lies immediately adjacent to the station. It was built deliberately in the then elite Nineteenth District of Vienna, not least to shore up Social Democratic voting in the district.

From here, there’s no direct route to Karl-Marx-Hof in the north but a trip on the tram to Karlsplatz and a rail journey from there to Heiligenstadt station takes around forty minutes and will give you an idea of the transport infrastructure that was vital to the Social Democrats’ urban programme. Karl Marx-Hof itself – or some of it as it’s pretty big (four tram stops from end to end to keep the transport focus going) lies immediately adjacent to the station. It was built deliberately in the then elite Nineteenth District of Vienna, not least to shore up Social Democratic voting in the district.

Karl Marx-Hof

What is there to say about Karl-Marx-Hof, built between 1927 and 1930, that hasn’t been said before? In some respects, the numbers alone are the most telling thing. Stretching 1100 metres along Heiligenstädter Strasse, the complex forms the longest contiguous residential building in the world. Its 1382 flats housed around 5000 people. Beyond homes, the overall scheme, designed by Karl Ehn, provided nurseries, a range of medical facilities, a library, shops, cafes and meeting rooms. (One of the former laundries now houses an historical exhibition on Red Vienna.) There was also a lot of open space: with just 20 percent of the 37-acre (15 hectare) site accommodating housing, the rest provided areas of rest and recreation including a number of children’s playgrounds.

‘Liberation’ and ‘Childcare’ by Josef Franz Riedl

Hopefully, the images can provide a sense of that scale and its architectural form. The ceramic sculptures by Josef Franz Riedl above the main archways represent ‘Enlightenment’, ‘Liberation’, ‘Childcare’ and ‘Physical Culture’ – an apt summary of the revolutionary purpose underlying the built form of Karl Marx-Hof. This was indeed, in the words of Owen Hatherley, ‘a rare example of architecture both as political instrument and ideological symbol’. (1)

Friedrich Engels Platz-Hof

From Karl Marx-Hof to Friedrich Engels Platz-Hof to the east is a 15-minute bus ride. Designed by Rudolf Perco, this was, with 1467 apartments, the second largest of the Red Vienna schemes after the Sandleitenhof in Ottakring. It is notable too for its more modernist appearance and ‘stark cuboid aesthetics’. It was one of the schemes to include a communal kitchen. The striking chimney of the communal laundry was described as a ‘new Viennese landmark’ at the scheme’s opening ceremony in 1933. (2)

Friedrich Engels Platz-Hof laundry tower

That ceremony took place in July 1933. Hitler had been installed Chancellor of Germany six months earlier and the defiant words of Karl Seitz, the Social Democratic mayor of Vienna who performed the ceremony, therefore held especial significance:

Even if the world is to become filled with devils, this Vienna will stand unmoved and firm, a haven of democracy, a haven of the spirit, a haven of liberty, a bulwark against fascism and dictatorship.

In the event, Red Vienna’s resistance to the Austro-fascist coup of Engelbert Dollfuss was brave but short-lived. Insurgents of the Republikanischer Schutzbund – the defensive paramilitary organisation of the Social Democratic Party – took up arms in February 1934, many based in the Gemeindebauten which were viewed by supporters and detractors alike as working-class fortresses, both in form and function.

Karl Marx-Hof, after shelling in February 1934, and a modern commemorative plaque

Reumann-Hof, George Washington-Hof and Karl Marx-Hof, amongst others, were scenes of heavy fighting but, facing both the full force of the Austrian state and the threat of heavy civilian casualties, they quickly surrendered. Up to 1000 members of the Schutzbund were killed; severe political reprisals followed. For the time being, the transformative political project of Red Vienna had come to an end.

Without detracting from that ambition and daring, it’s worth in conclusion assessing the impact of that project. In practical terms, even by contemporary standards: (3)

the individual apartments in the Gemeindebauten were small and minimally equipped. They had running water, toilets, gas, and electricity but no ‘luxury fittings’ such as bathtubs or showers, built-in cupboards, or closets.

Three-quarters of the apartments, into the mid-1920s, were no larger than 38 square metres (just over 400 square feet) in size and comprised only a small entrance hall, living room and kitchenette, toilet and one full-sized room.

Karl Marx-Hof

Decorative detail at the kindergarten of George Washington-Hof

The planning and political emphasis, of course, was on the schemes’ shared communal facilities – their laundries, washhouses, nurseries, cafeterias, libraries and meeting rooms. Through this community provision, together with homes far better and cheaper than they had known before, the Social Democrats’ urban programme was intended not only to consolidate political support for the party among the Viennese working class (which it very largely did) but herald and forge a new socialist consciousness.

To critics such as the Marxist Manfredo Tafuri, that was a ‘declaration of war without any hope of victory’, and the project – the Austro-Marxist belief in revolution through reform – essentially petit-bourgeois in conception and execution. In one sense, this judgement – given the events of 1934 and the 1938 Anschluss which incorporated Austria into Nazi Germany – is self-evidently true but I’ll leave the bigger ideological debate to others. (4)

Washhouse, laundry and ironing rooms of the Gemeindebauten

To continue for the moment this more sceptical strain, later revisionist historians have questioned whether even the greater freedom for women promised by the communal facilities was fulfilled in practice. Children weren’t eligible for kindergarten places till four; use of the laundries (under male supervision) was restricted to one allocated day per month. For many women, domestic duties and the double shift (of paid and home work) would continue to weigh heavily.

Political opponents have even labelled the whole enterprise, with its strict rules governing residents’ behaviour within and beyond their apartments, a form of benevolent but repressive paternalism. For my part, these rules might be read differently – as a conventional expression of working-class respectability, as recognition of the necessary consideration to others imposed by communal living, or just the rather typical rules imposed by landlords of all political stripes.

A courtyard at Friedrich Engels Platz-Hof

Against the enormous scale and sweeping aspiration of Red Vienna’s housing programme, such criticisms can seem querulous. They are a necessary reminder of real-world limitations and the perhaps unavoidable contradictions of any ambitious programme of political reform. But Vienna’s Social Democrats built homes for 200,000, provided high-quality educational, health and cultural facilities to many more, and led a regime which placed working-class needs and interests at its very heart – rare then, as rare now.

To a contemporary observer, the British journalist GER Gedye, they provided: (5)

the best object lesson in the world of what Socialism can and cannot do on a democratic basis in a Socialist capital of an anti-Socialist State.

And for all the tragic rupture of Nazism and war, that lesson lives on. The City of Vienna currently owns and manages over 226,000 homes, housing one in four – around 500,000 – of the city’s population. Red Vienna didn’t bring socialism and perhaps had only limited success in forging a new socialist consciousness but it did, in the earlier words of Social Democratic politician Robert Danneberg, ‘perform useful instalments of socialist work in the midst of capitalist society’.

In next week’s post, we’ll examine Alt-Erlaa, a contemporary showpiece of Viennese social housing, and housing policy since the Second World War.

Notes

For a good film essay on the history of Vienna’s social housing, see Angelika Fitz and Michael Rieper, How to Live in Vienna (2013) with English subtitles.

Sources

(1) Owen Hatherley, ‘Vienna’s Karl Marx Hof: architecture as politics and ideology’, The Guardian, 27 April 2015

(2) Liane Lefaivre, Rebel Modernists: Viennese Architects since Otto Wagner (Lund Humphries, 2017)

(3) Eve Blau, The Architecture of Red Vienna, 1919-1934 (MIT Press, 1999)

(4) Manfredo Tafuri, Vienna Rossa (Electa, 1980) quoted in Eve Blau, Re-Visiting Red Vienna as an Urban Project.

(5) Quoted in Blau, The Architecture of Red Vienna, 1919-1934

The fullest and most detailed guide to the individual schemes is provided (in German) on the City of Vienna’s Wiener Wohnen website.