My second post marking Open House London 2019 offers a broadly chronological, whistle-stop tour of the municipal seats of government featured, in various forms – some grand, some humble – on the weekend of 21-22 September. (Open House venues are picked out in bold with links to their web page; the links in bold blue relate to previous blog posts.)

City of London Guildhall © Prioryman and made available through Wikimedia Commons

It’s appropriate then to begin with the oldest and one of the most impressive of these, the City of London Guildhall and its present Grand Hall, begun in 1411 – the third largest surviving medieval hall in the country. Externally, it’s probably the 1788 grand entrance by George Dance the Younger in – with apologies to contemporary sensibilities – what’s been called Hindoostani Gothic that is most eye-catching.

Vestry House Museum, Walthamstow

At the other end of the scale what is now the Vestry House Museum in Walthamstow is a modest affair. It started life in the mid-18th century as a workhouse but included a room set aside for meetings of the local vestry. It was later adapted as a police station before becoming a very fine local museum in 1930. If you can’t make Open House, do visit it and Walthamstow Village at another time.

Old Vestry Offices, Enfield © Philafrenzy and made available through Wikimedia Commons

The Old Vestry Offices in Enfield, a small polygonal building built in 1829, originally housed the local beadle – responsible for local enforcement of the Poor Law – and then, until the 1930s, a police station.

This was an era of minimal – so-called night-watchman – local government when ad hoc, largely unrepresentative bodies administered basic services principally related to public health and safety. London’s first city-wide administration was created in 1855 in the Metropolitan Board of Works. This was initially a body of 45 members, elected indirectly by 43 London districts: the Vestry in 29 of the larger parishes and 12 District Boards of Works in which smaller parishes were combined (plus special bodies in the City and Woolwich if you’re counting).

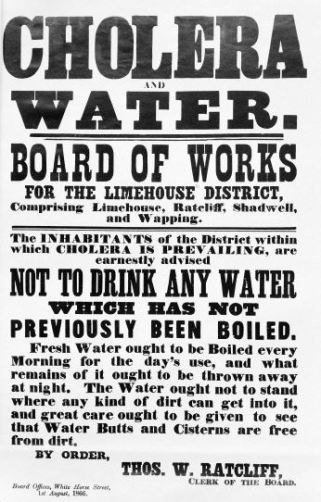

Limehouse District Board of Works, now the Half Moon Theatre

The Limehouse District Board of Works built headquarters on White Horse Road in Ratcliff. The building, erected between 1862 and 1864, was designed by the Board’s surveyor, CR Dunch – a ‘liberal interpretation of Italian Renaissance’ according to Pevsner.

Within four years the Board was grappling with one of the latest and largest of the cholera outbreaks to afflict London in this period – its sound advice to locals to avoid drinking potentially unsafe water availing little against the terrible sanitary conditions of the area.

Appropriately, after 1900 the building would house the Borough of Stepney’s Public Health Department. In 1994, it became the home of the Half Moon Theatre, committed to giving ‘young people an opportunity to experience the best in young people’s theatre’.

Shoreditch Town Hall

Shoreditch Town Hall almost matches the Guildhall in its civic pretensions – chutzpah indeed for a building, designed by the impressively named Caesar Augustus Long and opened in 1866 for a vestry. But Shoreditch Vestry took particular pride in its path-breaking municipal electricity undertaking and here its motto, and that of the later Borough, ‘More Light, More Power’ took on more than merely metaphorical meaning. You might recognise the figure of ‘Progress’ enshrined in the Town Hall tower too. After a long period of decline, the Town Hall was reopened in 2005 and is now a thriving community venue operated by the Shoreditch Town Hall Trust.

Old Hampstead Town Hall

Old Hampstead Town Hall was, in inception, another vestry hall – designed by HE Kendall and Frederick Mew in Italianate style and claimed as ‘a decided ornament to that part of Haverstock Hill’ by the local press when opened in 1878. The Metropolitan Board of Works was abolished in 1889 and replaced by the London County Council. London Metropolitan Boroughs were established in 1900. The building became the headquarters of the new Metropolitan Borough of Hampstead and was extended in 1910.

Limehouse Town Hall

Another building to undergo this transformation was Limehouse Town Hall, opened in 1881 and designed in Italian palazzo style by local architects Arthur and Christopher Harston as ‘a structure that…shall do honour to the parish of Limehouse’. The vestry hall became the offices of Stepney Metropolitan Borough Council – while its great hall hosted balls and concerts and even early ‘cinematograph’ shows. It was well known to Clement Attlee, mayor of Stepney in 1919 and later the area’s MP. It’s been run by the Limehouse Town Hall Consortium Trust as a community venue since 2004.

Richmond Old Town Hall

Richmond, a municipal borough founded in 1890 in the County of Surrey, was a more conservative body although it can boast (since its incorporation into Greater London in 1965) the first council housing built in the capital. Richmond Old Town Hall, also designed in Elizabethan Renaissance style by WJ Ancell, was opened in 1893 and now houses (since the creation of the London Borough of Richmond) a museum, gallery and local studies archives amongst other things.

Croydon Town Hall and Clocktower

Croydon, created a County Borough within Surrey in 1889, didn’t amalgamate with London until 1965 but the Town Hall, built to plans by local architect Charles Henman, was opened in 1896 to provide ‘Municipal Offices, Courts, a Police Station, Library and many other public purposes’. The Croydon Town Hall and Clocktower complex retains some local government functions – the Mayor’s Parlour and committee rooms – but also offers a museum, gallery, library and cinema.

Tottenham Town Hall, fire station and public baths illustrated in 1903

Tottenham Town Hall today

A visit to the Tottenham Green Conservation Area gives you an opportunity view a whole slew of historically significant buildings. With my municipal hat on, I’ll draw your attention to Tottenham Town Hall (HQ of Tottenham Urban District Council from 1904 to 1965) and the other examples of local government endeavour and service adjacent – the public baths next door (now just the façade remaining but, as the Bernie Grants Art Centre supported by Haringey Council, still serving a progressive purpose), the fire station (now an enterprise centre), and technical college (built by Middlesex County Council). Passing the new Marcus Garvie Library, you’ll come across Tottenham’s former public library built in 1896 just up the road. It’s as fine an ensemble of civic purpose and social betterment as you could find in the country. Some further images here.

Lambeth Town Hall

Lambeth Town Hall can’t compete with that but it’s a fine building, also Edwardian Baroque, whose redbrick and Portland stone facades are capped by an imposing corner tower. It was the work of Septimus Warwick and Austen Hall, and was opened on 29 April 1908 by the then Prince and Princess of Wales. Its dignified council chamber and some lavish interior rooms remain impressive.

Bethnal Green Town Hall, now the Town Hall Hotel and Apartments

Bethnal Green Town Hall, now a hotel, was opened in 1910 to Edwardian Baroque designs by Percy Robinson and W Alban Jones. Sculptures by Henry Poole adorn the exterior. The growth of local government responsibilities in the interwar period compelled the opening of a large extension to the rear, designed by ECP Monson – restrained neo-classical outside, sumptuous and modern inside – in 1939. (Monson was also a significant architect of the era’s council housing such as the briefly notorious Lenin Estate built in the 1920s when the Council was briefly under joint Labour-Communist control.)

The UK Supreme Court, formerly Middlesex Guildhall © Pam Fray and made available through a Creative Commons licence

Moving to the immediate pre-war period, the Middlesex Guildhall in Westminster – originally housing, amongst other things, the offices of Middlesex County Council – was an unusual building for its time, designed by Scottish architect James Gibson in free Gothic style and opened in 1913. It was sympathetically adapted in 2009 to serve as the headquarters of the UK Supreme Court.

Islington Town Hall © Alan Ford and made available through Wikimedia Commons

Islington Town Hall, opened in 1925, takes us into the heyday of local government as councils assumed ever greater powers and purpose. It was designed by ECP Monson again. Its neo-classical style has been described as old-fashioned for its time but it’s finely executed.

Kingston Guildhall, 1935 © Kingston History Centre

Kingston Guildhall was opened in 1935, designed for the Royal Borough of Kingsto-upon-Thames by Maurice Webb in contemporary neo-Georgian style though, more unusually in red brick with dressings in Portland stone. Two extensions were added in the 1970s and 1980s after the creation of the new London Borough of Kingston-upon-Thames and its incorporation into the area of the Greater London Council.

Hackney Town Hall

Hackney Town Hall, designed by Henry Lanchester and Thomas Lodge, is also formally neo-classical but its lines and styling are sleeker, more modern and, internally it’s a masterpiece of Art Deco. The Town Hall was formally opened in 1937 by Lord Snell, Labour Leader of the House of the Lords, he described it as a building:

devoted to the business of living one with another to the benefit of all…It represented something more than mere stone and wood put together; it embodied the ideal of social living…a symbol of their idealism and a focal point for the services of their great borough, and he hoped they would find in it an atmosphere of quiet dignity, purity of administration and of love for the purpose to which it was devoted.

London City Hall © Garry Knight and made available through a Creative Commons licence

Finally, we can bring the story up to date by referring to the latest iteration of London local government. Mrs Thatcher abolished the Greater London Council in 1985; the The new Greater London Authority was established in 2000. City Hall, the home of the Mayor of London and Greater London Assembly, was opened two years later – a high-tech building created by Norman Foster and Partners. Not everybody likes its appearance but the building is notable for reflecting current imperatives of sustainable design.