Last week’s post looked at the LCC’s open-air sculpture exhibitions but arguably the more significant contribution to the worthy attempt to bring art to the people lay in its ‘Arts Patronage Scheme’ inaugurated in 1956. By 1964 when it (and the LCC) were wound up, over 70 works of art had been purchased – adorning schools and housing estates across the capital.

Henry Moore, Two-Piece Reclining Figure No. 3, the Brandon Estate, Lambeth © Steve Cadman and made available through a Creative Commons licence

Many of these were significant pieces by some of the leading artists in the country. Nearly all were modernist works and its efforts were not, therefore, without controversy but they remain: (1)

outstanding in their ambition and coherence…In this respect, the LCC may be said to have assisted in the democratisation, if not the socialisation, of art.

The origins of the scheme are marked by their time and place. Although a Conservative government ruled, a broadly social democratic consensus prevailed which held that a progressive and classless society would be achieved, in part, by a democratic civic culture. In this, the arts would be a shared patrimony, neither solely derived from nor confined to a cultural elite.

Practically, there was a feeling – as the years of a genuine rather than enforced and politically motivated austerity passed – that the LCC could now look beyond immediate necessities and broaden its efforts to improve Londoners’ quality of life. In 1954, Isaac Hayward, Labour Leader of the LCC, expressed his view that ‘the Council has both a cultural and an educational responsibility to do what it reasonably can to encourage and assist in the provision of works of art’. (2)

If that, to jaundiced eyes, might reek of middle-class do-goodery, take another look. Isaac (‘Ike’) Hayward was a former South Wales miner (he started work down the pits aged 12) brought to London by his trade union work. A councillor for Rotherhithe and Deptford, he had been chair of the Public Assistance Committee which reformed the Poor Law before playing a key role in introducing comprehensive education to the capital. The Royal Festival Hall – designed and constructed by the LCC – was built under his determined leadership. The Hayward Gallery remains a fitting tribute to his role.

In 1956, with the approval of the Conservative Minister of Education, the LCC set aside £20,000 annually (the equivalent of perhaps £0.5m in present-day terms) for the purchase of artworks. It was thought ‘a reasonable sum’ at a time when the LCC was spending around £20m a year on ‘new architectural work and open-space development’. Some of the money was to be spent on the acquisition of existing works of art but the bulk was to go towards ‘the commissioning of new work and the encouragement of living artists’.

The LCC understood the sensitivities involved in this: (3)

The Council’s fundamental problem in running the scheme lies in the collective exercise of taste: an exercise which has to be accepted by those who provide the money, by those responsible for the service concerned, and by those who ultimately have to live with it.

And, as it acknowledged, such sensitivities were exacerbated by the predominantly modernist form of the works themselves:

Because most of the works acquired were to be associated with the Council’s own contemporary architecture, they have in practice been examples of contemporary style in art. This has sometimes been the cause of criticism, particularly where advanced design was in question.

It’s a valid point. Traditional statuary – a classicist monument or some ‘great man’ memorial – would have been as visually out of place as it was politically inappropriate. But the public art debate was usually couched in ideological terms: between modernists (criticised by some as ‘highbrow’ and ‘difficult’) and traditionalists who defended representational art and, they claimed, the taste of the ‘man in the street’.

For all that sound and fury, however, there were relatively few open controversies around the Council’s selections. A Reg Butler figure for the new Crystal Palace Recreation Centre commissioned in 1961 and eventually rejected was criticised by the Times as too abstract and opposed by a local Conservative councillor who wanted something with ‘the themes of vigour, strength or sport’. He concluded that: (4)

All this is just another symptom of the current mystique of art – that it is much too clever for ordinary people to understand. There are very clever things to be seen now in Battersea Park, and let no-one suggest that they are a load of old iron.

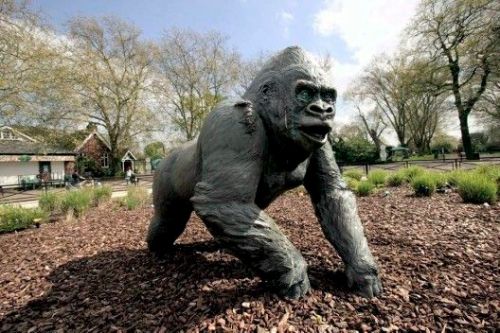

In the meantime, David Wynne’s Gorilla was installed nearby – a much safer and more popular choice at a time when its model Guy was a star attraction at the London Zoo. A John Hoskins sculpture intended for the Chicksand Estate in Whitechapel was also rejected as ‘too advanced’ by the Housing Committee.

But, conversely, the LCC, which had wanted a representational work at the Elmington Estate celebrating the poet Browning’s connection with Camberwell, ended up with a more abstract piece in Willi Soukop’s wall relief, The Pied Piper of Hamelin. (The sculpture was removed in 2000 when parts of the Estate were renovated but, to Southwark’s credit, has recently been restored to a wall at the adjacent Brunswick Park Primary School.)

In general, the LCC’s selections reflect (in words quoted by Margaret Garlake) an ‘aesthetic eclecticism’. This might reflect the cumbersome approval process involving – in fairly indecipherable fashion – departmental proposals, a Director of Arts, the Council’s General Purposes Committee and its Special Development and Arts Subcommittee and, finally, an Advisory Body on Art Acquisition itself advised by the Arts Council. By some bureaucratic magic, public art emerged.

General themes and trends do stand out, however. The earlier selections were marked by more thematic or obviously humanist content. Siegfried Charoux’s The Neighbours, located in the Highbury Quadrant Estate in Islington is an example of this; Geoffrey Harris’s Generations in the Maitland Park Estate off Haverstock Hill, Camden, another.

Geoffrey Harris, Generations, Maitland Park Estate, Camden © Stu and made available through Wikimedia Commons

Some later works, such as Robert Clatworthy’s Bull, erected on the Alton Estate, Roehampton, in 1961 have a more obviously modernist sensibility. Henry Moore was, of course, the prime contemporary exponent of the genre and two of his most prestigious works were placed in showpiece LCC estates – Two-Piece Reclining Figure No. 3 in the Brandon Estate, Lambeth, in 1961 and his Draped Seated Woman in the Stifford Estate, Stepney, in 1962.

Some of you will know the recent controversy that has surrounded this last work, affectionately known as Old Flo to local residents. It was sold to the LCC by Moore at the knock-down price of £7000 – a mark of his own commitment to public art – and based in part on his celebrated Wartime Shelter drawings of East End residents taking refuge underground from the Blitz. It represents, to its supporters, ‘the post-war desire to improve the lives of Londoners’ – its story ‘one of idealism, resilience and the marking of social change in London’. (5)

That continuing social change was further marked by the demolition of the Estate’s three tower blocks in the 1990s. Old Flo was removed and later moved for safekeeping to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. In 2012 the then Mayor of Tower Hamlets, which claimed ownership , proposed to sell it off for £20m – a tempting sum for a cash-strapped and impoverished east London borough. To cut a long story short, a public campaign in its defence, legal action and the recent change of political leadership in the Tower Hamlets appear to have saved the sculpture – and some of that vision it embodied – for the Borough though a new local location it is yet to be found. (6)

But this is only one element of the threat that these public artworks face. Theft is another – the fate which befell one of the three figures contained in Lynn Chadwick’s The Watchers unveiled on the Alton Estate in Roehampton in 1966. Having ‘discovered’ (their own words) the statues in their grounds, Roehampton University are now committed to re-casting the lost piece and safeguarding the work in the grounds of their Downshire House hall of residence. (7)

Another threat is sheer neglect and this perhaps is the most telling. We have travelled a long way from the idealism of the post-war world. Local government, once a flagship of a new and more democratic world, is now a beleaguered institution, its budgets cut to the bone, left fighting to defend its front-line services.

All that, inseparably, marks the new dispensation under which our state, society and culture labour – a world in which we know the price of everything and the value of nothing. The classless civic culture envisaged by Ike Hayward and the LCC seems a lost dream but we can and should value its remains.

Postscript

I hope to write more on this topic. Much remains to be said on the LCC’s programme of school artworks and the less ‘high arts’ elements of its support for public art. I’d be pleased to hear from anyone with memories, detail or photographs of lost or remaining LCC public artworks and would also be delighted to hear of municipal public art across the country.

Sources

(1) Margaret Garlake, ‘”A War of Taste”: The London County Council as Art Patron, 1948-1965’, The London Journal, vol 18, no 1, 1993

(2) Dolores Mitchell, ‘Art Patronage by the London County Council (L.C.C.) 1948-1965’, Leonardo, Vol. 10, 1977

(3) London County Council, ‘Patronage of the Arts Scheme’ (1966), London Metropolitan Archives, GLC/DG/PUB/01/364/U2336

(4) Quoted in Garlake, ‘”A War of Taste”: The London County Council as Art Patron, 1948-1965’

(5) Art Fund, ‘Henry Moore’s Draped Seated Woman: timeline of events’

(6) Mike Brooke, ‘People of the East End win High Court battle for Henry Moore’s “Old Flo”’, East London Advertiser, 9 July 2015

(7) The theft is recorded in ‘Second bronze sculpture stolen’, The Guardian, 24 January 2006; the University’s commitment to restoration and safeguarding in University of Roehampton, ‘Sculpture to stand watch over Roehampton once again’, 20 February 2015.

Especial thanks go to @SirWilliamD for answering an early Twitter query and supplying copies of the original sources which inform this post. Any errors, of course, are all mine.