Tags

If you’ve been following recent posts, you will have read already about the award-winning design and prestige of the Pepys Estate in its earliest years and its subsequent reputation as a crime-ridden and racist ‘problem estate’. Today’s brings the story up to date.

After 1979, a political attack on council housing was matched by an apparently more benign concern (although with a conveniently shared language of crisis and failure) to regenerate so-called problem estates up and down the country. As such, the Pepys Estate was ripe for intervention. This post examines the controversies surrounding its regeneration and their lessons which, in the context of some proposed solutions to London’s current housing crisis, seem as relevant than ever.

The first phase of the Estate’s transition was not controversial – in fact, it embodied precisely the conventional wisdom of its day. Crime was high: 175 burglaries and 392 car crimes were reported in 1982. Fear of crime was perhaps higher: (1)

Many old people, women and children are afraid to use the lifts or stairs and will not do so unaccompanied. Nor do residents feel confident to confront noisy children, boisterous teenagers or non-resident intruders, because they cannot rely on the support of other residents.

Reflecting the fashionable theories of Oscar Newman and his British alter-ego Alice Coleman, blame for crime and antisocial behaviour was placed on the Estate’s design:

the inter-connectedness, the lack of ‘defensible space’ and opportunity for surveillance over common parts and the ease of access to and escape from the blocks.

That inter-connectedness had, of course, been one of the founding design ideals of the Estate and had once succeeded not only in the practical aim of separating pedestrians and traffic but in promoting community. Now, by some alchemy, ‘the massive “streets-in-the-sky” catwalks separating pedestrians from traffic had become liabilities that destroyed neighbourhood connections’. (2)

A Safe Neighbourhoods Unit Action Plan was presented in April 1982 and a series of measures to improve security followed – strengthened front doors to flats, double-entry phone systems to blocks, and CCTV. A concierge system was trialled in Aragon Tower in a later phase of the scheme and walkways demolished between two of the medium-rise blocks, Bence and Clement Houses. At the same time, a Neighbourhood Housing Office was established on the Estate and policing stepped up. It was reported, as a result, that recorded crime had fallen by over half by the end of the decade though street crime less so.

If I’ve treated this initiative somewhat provocatively, perhaps I shouldn’t. The improvement to residents’ lives was real and there’s no reason why secure entry systems and concierge schemes should be confined to middle-class developments. Crime should, of course, be ‘designed out’ where feasible.

My scepticism lies only in the tendency of some to assume design flaws were (here and elsewhere on other similar estates) the cause of crime. We saw last week the range of social and economic challenges this previously safe and well-regarded estate faced by the 1980s and, given the demographics (just under a quarter of the Estate’s population was under 18), we might look to a far wider range of factors to explain both the rise and fall of antisocial behaviour.

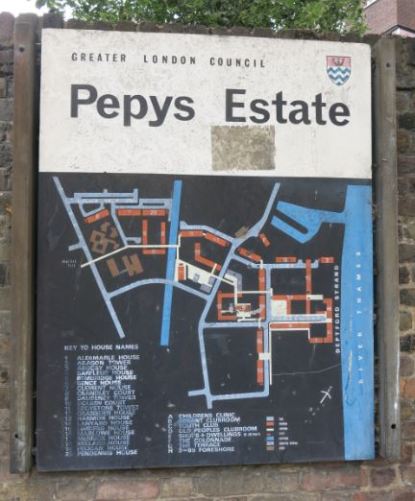

A contemporary but out-of-date Lewisham Homes sign for the Estate – Merrick House is gone but the former shopping terrace is still shown

Regeneration proper began in 1992 when the Department of Environment approved the Deptford City Challenge initiative, a seven-year programme scheduled to spend almost £29m on reviving and renovating the Estate.

After extensive consultation with residents, the initial Estate Action programme which emerged proposed the demolition of just one housing block – the 44 flats of Merrick House in the centre of the Estate to be replaced by 18 new three- and four-bed houses with their own enclosed gardens. Some walkways and the existing Community Centre and elevated shopping centre were also to be rased and replaced.

In the plethora of interventions of the time, a Pepys Community Forum secured (excuse the jargon, just for the hard-core social housing enthusiasts among you) Single Regeneration Budget Round 5 funding. This resident-run community development trust survives to the present and among its initiatives is the Evelyn Community Garden on Windlass Road. (3)

Eddystone Tower with the new shops and community centre, occupying the former area of Merrick House, in the foreground

Merrick House and the shops came down (although the current small street-level terrace is far smaller and inferior in provision) and the refurbishment of existing blocks proceeded through the mid-1990s. But events were to take a radically different turn from 1998 when Lewisham Council carried out a residents’ survey to review works carried out and plans for the future.

The survey appears to have been intended to provide cover for decisions already taken. Both the Pepys Neighbourhood Committee and Pepys Regeneration Forum objected to its format, which was taken to pre-judge outcomes, and the secrecy which surrounded its findings.

The controversial Lewisham Council advert intended to ‘sell’ the changed plans for the Estate to local residents

In 1999, the Council abandoned the proposal to build new family homes in the centre of the Estate and announced, contrary to existing promises, plans to demolish five of the Estate’s low-rise blocks (Limberg, Dolben, Barfleur, Marlowe and Millard Houses) and sell off Aragon Tower.

These blocks were indistinguishable from others on the Estate, all but Barfleur had already been improved under the Estate Action scheme, and an architectural survey commissioned by tenants found them to be structurally sound. They shared one characteristic, however: they happened to be closest to the river – ‘the area most amenable…to gentrification’. (4)

At the same time, the Hyde Housing Association was selected by the Council as its preferred partner in the proposed redevelopment and the Association – acquiring the blocks for £6.5m and receiving £9m from the Housing Association for its own scheme – was granted planning permission to demolish and rebuild one year later. All this, despite some fairly cosmetic consultation, took place behind closed doors. The scheme required the ‘decanting’ of existing tenants in 222 council flats who were offered no right of return. Tenants groups and housing activists mobilised in protest.

The new scheme – five blocks of flats plus two terraces of three-storey houses in its initial phases – was designed by the bptw practice (architects don’t like capital letters apparently). This was a mixed tenure scheme (as now deemed necessary) – of the first 169 homes, 45 were for shared ownership and 124 for social rent – but it was also, more positively, tenure blind.

The scheme won an award as the Best Public Housing Development in the 2005 Brick Awards and was selected as a (positive) case study by CABE, the Government’s Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. (5) To my untutored eyes, the new blocks along Foreshore, Longshore and Barfleur Lane look attractive, albeit in a generically contemporary way. Owen Hatherley is more cynical: (6)

The new blocks are regeneration hence good, the old are council housing hence bad. Yet the council flats are much larger, and look much more robustly built, of concrete and stock brick – the newer flats are clad in the ubiquitous thin layer of brick or attached slatted wood, materials which have shown an unfortunate tendency to fall off.

At least most of these homes remained more or less genuinely affordable (though presumably at higher Housing Association rents). The sale of Aragon Tower to Berkeley Homes for £11.5m in 2002 was pure and unabashed gentrification and has resulted in the loss of 144 council flats. Berkeley Homes added five floors to the existing 24-storey tower and 14 penthouse units. One of the refurbished former council flats – ‘a superb two bedroom split-level flat within a fantastic modern development with concierge service, boasting a bright and contemporary living space’ – was recently sold by Foxtons for £440,000.(7)

To avoid any taint of council estate, a new entrance was constructed on the western side of the Tower from George Beard Road and early prospective purchasers were brought down by Thames Clipper to Greenland Pier upriver. All this was described in a BBC documentary series in 2007, The Tower: a Tale of Two Cities. Perhaps you’ve seen it; I haven’t and it’s not available online. There are mixed views of the series on the Estate but it does, at least, seem to have done a pretty good job exposing the stark social and economic divisions which currently shame us. (8)

Lewisham Council claimed to have run out of money and it’s true enough that the rules of the game were – and are – designed to curtail the ability of local councils to improve and expand their housing stock. But it suited, too, a gentrifying agenda which sees some London councils only too keen to bring the middle-class and their money into their boroughs.

This was expressed honestly by Pat Hayes, the Council’s director of regeneration: (9)

The key to successful communities is a good mix of people: tenants, leaseholders and freeholders. The Pepys Estate was a monolithic concentration of public housing and it makes sense to break that up a bit and bring in a different mix of incomes and people with spending power.

Of course, one doesn’t hear much of ‘monolithic’ middle-class suburbs, nor – although they exist (and existed once on the Pepys) – of ‘successful’ working-class communities. And wouldn’t it be better if those ‘people with spending power’ were local people treated more fairly in our unequal society?

In reality, this form of ‘regeneration’ is all too often imposed at the expense of the existing community and against council tenants’ wishes and interests. On the Pepys Estate, it resulted in the loss of 366 secure council tenancies. (10) As areas all around the Estate are redeveloped privately, the suspicious lull in current remedial works on remaining blocks in the care of Lewisham Homes leads some to believe the process may not be over.

The £11.5m secured from the sale was promised to housing schemes elsewhere in the Borough. Still, you can do the maths – Berkeley Homes were the real winners. It’s a perfect illustration of the skewed values and insane economics which currently shape the UK’s housing market.

Daubeney Tower with Aragon to the rear surrounded by old and new build © Derek Harper and made available through a Creative Commons licence

The Pepys Estate, let’s be fair here, has clearly benefited from much of the renewal which has taken place. The Estate looks and feels good now; its homes are of a quality and at rents which millions of private renters dream of. It remains a living example of the ambition and idealism of earlier generations to secure good, healthy, secure and affordable homes for ordinary people.

Ironically, the Surrey Canal – maintained as a feature in the GLC’s lay-out of the Estate but covered over during redevelopment – is now scheduled to be re-opened as a linear park. Gentrification has obviously made water features respectable again.

A penthouse apartment view from Aragon Tower as featured in the Sprunt architectural group’s flyer for the development

But if you want a stark symbol of current free-market politics and our new priorities ponder on the fact that a tower block, part of an estate built ‘for the peaceful enjoyment and well-being of Londoners’, is sold off to the wealthy because it’s next to the river and too good for the working-class.

Sources

(1) The 1982 Safe Neighbourhoods Report quoted in Tim Kendrick, Housing Safe Communities: an Evaluation of Recent Initiatives – the Pepys Estate, London Safe Neighbourhoods Unit (ND)

(2) Gareth Potts, Regeneration in Deptford, London (September, 2008)

(3) Jean Anastacio, Ben Gidley, Lorraine Hart, Michael Keith, Marjorie Mayo and Ute Kowarzik, Reflecting realities Participants’ perspectives on integrated communities and sustainable development, Joseph Rowntree Foundation (July 2000) and Malcolm Cadman, Pepys Community Forum

(4) Michael E. Stone, Social Housing in the UK and US: Evolution, Issues and Prospects (October 2003)

(5) CABE, Case Study: Pepys Estate, Deptford, London

(6) The London Column, Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, Text Owen Hatherley (May 2011). The blogger Single Aspect has also criticised the re-design of Aragon Tower.

(7) Foxtons, Two-bed flat for sale, Aragon Tower, Deptford SE8

(8) You can see the series being discussed by residents on the Spectacle Productions website

(9) Sarah Lonsdale, ‘Tears of a clown as his tower gets a fancy facelift‘, Daily Telegraph, November 12 2004

(10) For blow-by-blow details and analysis of the process, see the online archive created by Malcolm Cadman of the Pepys Tenants’ Action Group including his Chronology of Events and Tenants Action Group Pepys Archive. For another highly critical account, go to Keith Parkins, ‘Scandal of Pepys Estate’, on Indymedia, February 9 2005