My apologies for the long delay in updating the blog but it remains an ongoing project. After all, with something over 6 million council homes in Britain in the early 1980s, there’s quite a lot to cover. In the meantime, I’m also always pleased to welcome guest contributions from people with particular local knowledge or experience. Today, I myself am offering a brisk survey of Gloucester, a city with its unique characteristics but one, in other respects, that provides a typical but illuminating history of council housing.

Gloucester dates back to Roman times and by the First World War was a long-established cathedral city and county town; a reformed corporation in 1835 and a county borough from 1889. It also boasted a significant industrial presence as an inland port and railway hub and, increasingly into the interwar period, a growing engineering sector. Despite a rapidly rising population – increasing from around 17,500 in 1851 to just over 50,000 in 1911 – the Council had built no council housing before 1914.

As was typical, the First World War and its aftermath changed that. Legislatively, the 1919 Housing and Town Planning Act required local authorities to survey housing needs and, where necessary, prepare plans to meet them with generous support from the Treasury. Politically too, there was a demand for reform, the ‘Homes for Heroes’ that Lloyd George had promised. Gloucester, however, remained for the most part a conservative city: in 1919 Labour returned just two councillors of the forty total (at its interwar peak in the later 1930s it returned six). A Conservative majority was further entrenched by an ‘anti-socialist’ alliance with the Liberal Party from the early 1920s.

Nevertheless, the Borough Council formed its first Housing Committee in 1919 and announced its first ‘assisted housing scheme’ of 280 houses in what is now called, for obvious reasons, the Oval district south of the city centre. Fulfilling that promise of high-quality housing, all but twenty of these were parlour houses (with that front room typically kept for best in working-class circles) laid out at around eight per acre, below even twelve per acre recommended by the Tudor Walters Report.

The Gloucester Journal report captured the ambition: (1)

Altogether the plan under notice … deals with nearly 30 acres, which will be devoted to the laying out of Gloucester’s first ‘garden city’. It is intended that the houses shall be designed so as to give full effect, as far as possible, to health, utilitarian, and picturesque considerations, and it is probable … that they will be grouped in twos, threes and fours.

Furthermore, a quarter of the land was set aside as recreational open space.

Reflecting the desire to build at pace and scale, a deputation of councillors had visited Redcar to view the ‘Dorlonco’ houses built by the Dorman Long Company; these were steel-framed houses designed to be built on a mass scale but adaptable with a range of skins to suit local preference. A number were built on the new estate.

The Trades and Labour Council remained unimpressed by the apparent urgency. At ‘a well-attended mass meeting’, WL Edwards contended that: (2)

The slums of Gloucester would continue throughout their lifetime unless they altered the social system of the country. The City Council, composed principally of ‘blues and yellows’ were committed to 400 houses, whereas they could let 1,000 if they closed down the slums …

A severe outbreak of smallpox in the city in 1923 – 698 cases were reported though fortunately only three proved fatal – seemed to emphasise the need for housing and sanitary reform.

However, the generous assistance afforded to council house construction by the 1919 Act had been ended on cost-cutting grounds in 1921. Neville Chamberlain’s 1923 Housing Act offered subsidies to private builders providing working-class housing (and barred local authorities from building unless they could demonstrate private sector failure in this regard). Gloucester built 100 houses under its terms. Labour’s 1924 Housing Act, promoted by Clydeside MP John Wheatley, provided a bigger boost to council housebuilding.

In 1925, Gloucester’s early ‘concrete houses’ (as they became known) were described as ‘universally condemned’ by Labour councillor George Matthews who complained £1688 had been spent on the repair of some 280 houses, ‘few of which had been up six years’. (3)

But Labour’s plea for direct labour – a municipal building workforce – was rejected. In fact, the Council continued to look for forms of permanent prefabricated housing that would reduce the need for skilled construction workers. In this, they reflected the national drive for non-traditional construction spearheaded by Minister of Health and Housing Neville Chamberlain who believed the unionised building trades too highly paid and obstructive.

In 1926, the Council commissioned two experimental wooden bungalows and two experimental concrete houses. The latter at least must have proved successful in the short term as further contracts with the Monolithic Building Company Limited followed in 1927 and 1928 respectively for 150 and 68 semi-detached houses either side of Finlay Road. The unconventional appearance of the homes led to the new estate, officially opened by the Duke of Gloucester in July 1928, being nicknamed White City. (The name was finally given formal recognition in 2012.) The scheme grew to encompass just over 600 homes by 1939. Remediation work to tackle problems of condensation occurred in the 1950s but in the 1990s the concrete houses were demolished and replaced by housing association homes of conventional construction.

By the mid-1920s, the stated aim of the Housing Committee was to build around 300 new council homes annually but the pace of construction was still subject to criticism from both sides. WL Edwards, now a Labour councillor, pointed to the 1200 families in Gloucester living two to a house: ‘their schemes to date had provided 499 dwellings but they had 426 dwellings declared unfit for habitation’. He blamed profiteering for the £950 cost of houses built under the 1919 legislation. Conversely, Councillor Blackwell, a Liberal member of the anti-socialist majority, criticised the extravagance of the ‘garden city stunt’ of The Oval and called for denser housing. (4)

In 1930, Labour’s new Housing Act (the Greenwood Act) promoted slum clearance and the rehousing of those living in slum conditions. In the same year, the Borough Council compulsorily purchased land to the south-east of the city at Coney Hill that would form the basis of a new estate. Significantly, of the 258 houses built at Coney Hill between 1931 and 1933, 150 were set aside to those affected by slum clearance in the Westgate Street district – the result of a 1932 order demolishing 150 houses in courts and lanes in the Archdeacon Street and Island areas.

A 1935 boundary extension doubled the city’s acreage and including land incorporated in Wotton, Coney Hill, Matson, Lower Tuffley and Podsmead that would be significant to post-war council housebuilding. By the outbreak of war, the Borough Council had built 2115 council houses, a figure that – despite the criticisms – placed it in a respectable average among county boroughs.

Despite a heavy bombing raid that hit the industrial eastern edge of the city killing 148 in April 1942, Gloucester escaped relatively lightly from wartime bombing. Nor did the city experience a sweeping political transformation though Labour rose to hold 17 of the 40 council seats in 1945. There were smaller signs of post-war radicalism; for example, a deputation to the Housing Committee from the local Communist Party bearing a petition of 1000 signatures demanding an accelerated housing programme. (3) And, in the following year, the requisitioning of ‘four houses where the householders have not made available accommodation in excess of their needs’. (6)

In general, however, the Council was criticised for what the opposition believed to be its slow pace of housebuilding. A local newspaper headline proclaimed ‘Gloucester Behind in the Housing Race’; ‘well behind’, the article stated, the city having completed only 104 houses since war’s end by 1947 while nearby Cheltenham had provided some 400. (7)

Labour councillors proposed a ban on private housebuilding; the Labour government already prioritised those in greatest housing need by requiring councils to ensure that no more than 20 percent of new build was privately built. (8) Predictably, given the political complexion of the council, that motion was rejected. Instead, the leadership looked again – as was the national trend – to forms of prefabrication.

In 1947, the Housing Committee considered an experiment with ‘the “Taylor” house constructed of foamed slag or concrete blocks’. Since no more was reported (and the type seems very elusive), I assume this wasn’t followed through. The Council were on safer ground and reflecting national building programmes with Easiform housing, a form of in situ pre-cast concrete construction developed by John Laing and Son Ltd. The Council were allocated 100 Easiform houses (alongside 100 houses of traditional construction) in 1949. More would follow in the 1950s.

Another common post-war type (around 40,000 were built nationally) were British Iron and Steel Federation (BISF) houses with their characteristic steel-clad ‘tin top’. Many can be seen (nearly all converted) dotted around Gloucester with significant in concentrations in Tredworth Road and Highworth Road, Tredworth, and Highfield Road in Saintbridge.

One reason for the city’s poor housing performance by 1947 was the fact that it had not applied for or been allocated any of the temporary prefabs launched in1944 as a short-term response to the housing crisis. (Cheltenham was said to possess 241.) From 1948, however, Gloucester did invest heavily in prefabricated aluminium bungalows – the BL8 Hawkesley type, a natural choice since they were manufactured by the Hawksley Company, part of the Gloster Aircraft Company, based in Hucclecote on the city’s eastern edge. These were intended as permanent in contrast to the ten-year lifespan alloted to the bungalows built under the 1944 programme.

Significant numbers were erected around Shakespeare, Burns, Tennyson and Shelley Avenues in Tuffley and more nearby in the Tuffley Court Estate originally consisting of 300 permanent aluminium bungalows. Even the Tuffley Court Community Association Hall on Seventh Avenue, initially built in 1955 as a hybrid church and community centre was of non-traditional construction, using the Reema system of concrete construction. Ironically, locally listed, it’s now the only ‘prefab’ that survives. (10)

In 1950, some 2665 households were on the Council’s housing waiting list (11) but the city’s expansion was accelerating. There were boundary extensions to the south in 1951 and 1957 and a much larger one in 1967 that added almost 13 square miles as more of the city’s suburbs were incorporated. By the early 1970s, the city’s population stood at just over 90,000. Labour won control of the Council in 1957 and held power till 1966.

Two complementary characteristics marked the development of council housing in Gloucester and elsewhere from the 1950s as the country moved from tackling the immediate housing crisis to long-term reconstruction. One was slum clearance, concentrated in poorer inner-city areas; the other, was the large-scale development of suburban estates with, in metropolitan areas, a concomitant shift to high-rise construction.

The Matson Estate, to the south-east of the city, that would grow to comprise some 1500 homes, was begun in 1951. The Podsmead Estate, 500 homes, was built in the south-west from 1955. One year later, Phase I of the Lower Westgate Comprehensive Development Area, immediately to the west of Gloucester Cathedral, was declared.

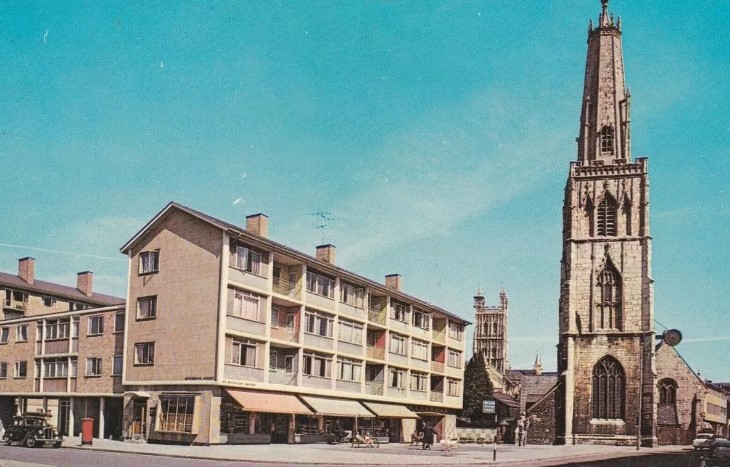

The suburban estates provided good quality housing in generous surrounds; inner-city redevelopment permitted greater architectural imagination. Sixty-four homes were built in four-storey maisonette blocks in St Mary’s Square from 1956. The Fountain Square scheme, immediately to the north, designed by City Architect JV Wall, was a larger mixed development project begun in 1958, comprising three to six-storey flat and maisonette blocks as well as retail and office accommodation facing Westgate Street, laid out in courts and open spaces giving views to local landmarks.

Architecturally, its very much of its time – a hybrid of the Festival style popular in the early 1950s that referenced contemporary Scandinavian design with touches of plate-glass modernism – but what stands out is the intention to design well and the attention to detail. The latter is seen in the sightlines consciously created, the checkerboard patterning applied to ground floor facades, and some public art: the rather incongruous statue of Charles II (not a local hero since he punished the town for its Parliamentarian sympathies in the Civil War) dating to 1662 but relocated to St Mary’s Square in 1960 and – since removed – the ‘Family Group’ statue installed in 1961 on Westgate Street, sculpted by local arts lecturer John Whiskerd.

Kingsholm, a little to the west, was a second Comprehensive Development Area planned in the early 1960s. Its first phase comprised three-storey maisonettes and flat blocks and what was to be Gloucester’s only (quite modest) tower block, the 11-storey Clapham Court. All were designed by the City Architect’s Department though for Clapham Court ‘the working drawings were completed by the contractors [Wates] under the supervision of the architects’. A tiled mural in the foyer of the block was designed by a student of Gloucester College of Art. Additional flats for elderly people and three-storey blocks were added in a second phase. (12)

The anonymous critic of the Architects’ Journal was a little sniffy about the Clapham Court slab block though careful to point out that criticisms – of its ‘long length of internal corridor’ and the ‘sense of isolation’ created – referred to the form in general rather than the Gloucester study in particular:

Architects can no longer delude themselves that people who prefer their friendly slums to the grand new blocks are just not aware of the benefits of good plumbing.

Further commentary referred to the angular layout of the blocks:

These buildings are bold and imaginative conceptions but in attempting to avoid sentimentality they have become a little unfriendly. This will probably appear less so when the scheme is finished and the planting matures.

Visiting recently, amidst mature greenery, I though it looked an attractive estate. Clapham Court itself now provides 80 one-bed sheltered homes but, citing estimated maintenance costs of £1m, its current owners Gloucester City Homes proposed its demolition in 2021. Plans to replace it with two lower blocks providing 36 homes are expected to be ratified by the Council this year. (13)

Returning to the sixties and an innovative City Architect’s Department gaining national attention, the Council also very unusually built 68 houses on Darwin Road at the city’s southern periphery for sale to those on the council housing waiting list, initially on a five-year leasehold and then freehold. Though critical of the layout and some cost-cutting, the Architects’ Journal analysis concluded that the scheme ‘must be a very pleasant place to live, with fine views and a pleasant environment’. At any rate, the homes sold quickly at between £2100 and £2150. (14)

Later in the decade, under a new City Architect, John R Sketchley, another Westgate scheme garnered notice – St Mary’s Close, an intimate development of 21 one and two-person flats maintaining local character through its ‘mellow red brick sympathetic with St Mary’s Square’ and ‘series of alleyways and courtyards with first floor bridges’. (15)

Meanwhile, a major redevelopment of the city centre seemed, as it emerged in practice, less sympathetic. Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe’s Comprehensive Plan for the Central Area of the City of Gloucester was published in 1961, its principal elements being the creation of the new King’s Square Shopping Precinct and the Eastgate Shopping Centre completed in the early 1970s. Both have been criticised – the former was subject to a large-scale refurbishment completed in 2022 – as has the rather disjointed and inconsistent form of the contemporary city centre (although there are interesting modernist and Brutalist buildings that may not be to everyone’s taste). Jellicoe was not responsible for the individual designs and declared himself disappointed by some of them. (16)

If that was a sign of planners’ hubris in the 1960s, by the end of the decade attitudes were changing. In housing terms, there was a strong shift from slum clearance and redevelopment to the rehabilitation of older properties formerly declared unfit. Tredworth, an area of older terraced housing south of the city centre, was the site of one the first General Improvement Areas declared under the 1969 Housing Act.

Having been a proud and unitary county borough since 1889, the City Council found itself relegated to a second-tier authority under local government reorganisation in 1974. Nevertheless, within its expanding borders the city continued to grow, principally through the development of large private estates though, from 1974, the Council built 378 homes on former Robinswood Hill barracks site in Matson.

Since then, of course, the housing landscape has changed and, for the moment and perhaps for the foreseeable future, the era of large-scale social housing construction ended. The impact of Right to Buy reduced the city’s council housing stock to just over 5700 homes by 1996.

By the early 2000s, the City Council was looking to implement the Large-Scale Voluntary Transfer (LSVT) of its housing stock to an independent registered social housing provider. LSVT had been introduced by the Conservatives in the 1988 Housing Act – Margaret Thatcher disliked local authorities (particularly Labour-controlled ones) and believed that housing associations offered more efficient and responsive management – but it took off under New Labour who shared some of the same attitudes. New Labour’s Decent Homes Standard, introduced in 2000, accelerated the process for while it produced a laudable improvement in the facilities and environment of council estates, for many councils it could only be financed by transferring their housing stock to bodies that enjoyed greater borrowing powers.)

Gloucester, however, took the apparently idiosyncratic decision to transfer its stock to North Housing, based in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The powerful Gloucester Tenants’ Federation, with the support of local churches and unions, launched a fierce campaign of resistance, led by its manager, a council tenant of thirty years’ standing and a former Conservative mayoress of the city, Anne Williams (she subsequently resigned from the party): (17)

When I heard the proposal to transfer Gloucester city council housing stock to North Housing Association I was gobsmacked. I thought: ‘What on earth’s going on?’ I’d never even heard of large-scale stock transfer and didn’t even know we had secure tenancies until we found out they could be taken away from us. It’s up to bolshie tenants like me to say: ‘There is another alternative to stock transfer and that’s staying as a council tenant with a secure tenancy.’

That may have slightly misrepresented the nature of the process – secure tenancies remained – but it captured well the resentment tenants felt about the transfer of their homes to an ‘absentee landlord’. The Council beat a retreat before the proposal could go to ballot and instead it retained ownership of its housing stock by transferring it to an arms-length management organisation, Gloucester City Homes (GCH). In 2015, GCH became an independent housing association and took direct ownership of its now 4452 homes.

New social rent housing is being built, albeit on a smaller scale. In Gloucester, the Tanner’s Hall scheme opened in 2021, in which 24 affordable rent flats have been incorporated into the remains of a 13th century townhouse, might claim to be both some of the oldest social housing built and some of the newest.

Regeneration of existing estates has been a more recent priority. In 2017, GCH secured funding of £1.25 million from the Government’s Estates Regeneration Fund to develop master plans for the regeneration of the Matson and Podsmead estates. In 2023, a £130 million finance package with Nat West was reported that will allow energy efficiency upgrades to existing homes and the construction of 400 new homes. Plans to improve facilities on the Podsmead Estate received a further boost in January this year following a land sale agreed by the City Council. Overall, it’s estimated that GCH has built around 125 new homes in the last two years. (18)

Council homes made a vital contribution to decent and affordable housing in Gloucester. Currently just under 14 percent of Gloucester households live in social housing but, with over 15,000 households on social housing waiting lists across Gloucestershire, the need for secure social rent housing remains as powerful as ever. Past investment has repaid itself many times over and will do so again if we empower councils and housing associations to build the homes our country needs.

Sources

(1) ‘Gloucester Housing Scheme’, Gloucester Journal, 17 May 1919

(2) ‘Housing in Gloucester’, Gloucester Journal, 28 February 1920. William Levason Edwards was the first Jewish mayor of Gloucester in 1932; he died in 1935.

(3) ‘Gloucester’s Houses’, Western Daily Press, 27 March 1925

(4) ‘The Housing Problem’, Gloucester Journal, 3 July 1926

(5) ‘Gloucester Housing Deputation’, Gloucester Citizen, 25 April 1945

(6) ‘Surplus Rooms in City Requisitioned’, Gloucester Citizen, 1 October 1946

(7) ‘Gloucester Behind in Housing Race’, Gloucester Citizen, 4 September 1947

(8) ‘Gloucester Housing Discussion’, Gloucester Citizen,1 May 1947

(9) Gloucester City Council, Townscape Character Assessment: Gloucester, June 2019

(10) Gloucester City Council, Gloucester’s Local List Version 1.3 (9 December 2022)

(11) ‘City Housing List Grows’, Gloucester Citizen 3 January 1950

(12) ‘Kingsholm’, The Architects’ Journal, 16 September 1964. For more detail and images, please see the interesting, recent post on Clapton Court by Adam Coleman.

(13) Ellie Hollinshead, ‘Proposal put forward for replacement of Clapham Court tower block’, The Business Desk, 18 December 2023

(14) ‘Darwin Road’, Architect’s Journal Information Library, 16 September 1964

(15) ‘Housing study: St Mary’s Close, Archdeacon Street, Westgate, Gloucester’, The Architects’ Journal, 1 December 1971

(16) For a good balanced account of the Jellicoe Plan and its impact, see ShadowedEyes, What Were They Thinking? Jellicoe, 3 May 2021. See also Adam Coleman’s ‘Kings Square Recovered‘ research project documenting phootgraphically the evolution of the square.

(17) My thanks to Tim Morton for bringing this episode to my attention – see his comment below. See also, Gemma White, ‘Meet the Resistance‘, building.co.uk, 8 August 2002

(18) See Jordan Marshall, ‘Gloucester City Homes agrees £130m funding deal as part of 400-home plan’, housingtoday.co.uk, 23 August 2023 and Nicky Godding, ‘Podsmead regeneration plan set for step forward in Gloucester’, housingtoday.co.uk, 31 January 2024