Last week’s post followed my walk exploring the housing history of Liverpool with Ronnie Hughes. We had a long, gloriously sunny Bank Holiday weekend in the city and lots more to do so what follows is a little more eclectic but, naturally, it remains firmly municipal.

In fact, later in the same day, I took time to time to visit what must be – alongside Eldon Grove – the most spectacular symbol of Liverpool’s housing history, St Andrew’s Gardens (or the Bullring to locals). I’ll let a couple of pictures do the talking first.

St Andrew’s Gardens (The Bullring)

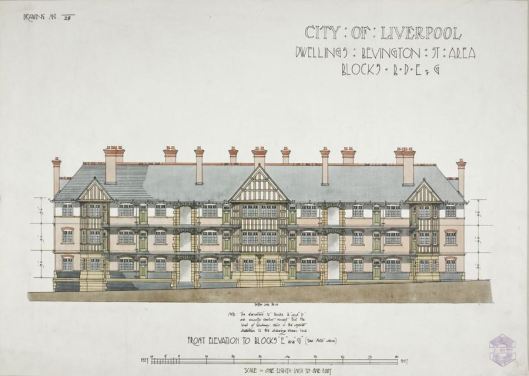

Impressed? St Andrew’s Gardens, designed by John Hughes, was built by the Corporation between 1932 and 1935, the first of a stunning series of multi-storey tenement blocks (inspired by the cutting-edge public housing of Berlin and Vienna) built under the visionary leadership of City Architect and Director of Housing Lancelot Keay.

This, mark you, is a remnant of the original scheme and other similar grand blocks such as Gerard Gardens have been completely demolished. To gain some sense of the scale and ambition of the latter, your best bet is to visit the Museum of Liverpool to admire the model constructed by Ged Fagan.

Gerard Gardens model, Museum of Liverpool

Just to the left of the model you’ll see a couple of original artefacts from the building – The Builder and The Architect: two reliefs by local sculptor Herbert Tyson Smith, commissioned by Keay to adorn its exterior.

The Builder and the Architect, formerly Gerard Garden now in the Museum of Liverpool

I’ve written in an earlier post about Liverpool’s unequalled interwar multi-storey housing. Now you just have St Andrew’s Gardens as a reminder of what was achieved – and it is student housing. There are currently about 50,000 plus HE students in Liverpool and the city has bet big on their presence as a contribution to the local economy. It had better hope that particular bubble doesn’t burst.

Back at St Andrew’s Gardens, you’ll see to the rear a more modern artwork depicting local people and their lives, created by Broadbent Studio in conjunction with the St Andrew’s Community Association and the Riverside Housing Association. It was unveiled by the Queen in 1999. It contains a biblical quotation from First Corinthians: ‘The eye cannot say to the hand I have no need of you, nor again the head to the feet I have no need of you’. I’ll take that as a tribute to the value of the lives and labour of the ‘ordinary’ people who once lived in the Bullring.

‘The Bullring’ artwork

On this day, the Queen was earning her pittance too, popping over the road to unveil what must be one of the most incongruously-placed plaques in the country at 19 Bronte Street. All this was to mark the area’s ‘regeneration’.

19 Bronte Street

It all creates a strange mix (but Liverpool is a city of clashing contrasts) as the new build here in Gill Street and the older, 1960s (?) housing nearby in Dansie Street illustrates. Obviously Frederick Gibberd’s Metropolitan Cathedral is a looming presence too.

Gill Street

Dansie Street

OK, now for some unashamed tourism but you can’t visit Liverpool without ‘doing’ the Mersey and the Beatles…and, with eyes to see, there’s plenty of significant municipal history in those too.

Wikipedia probably isn’t the most reliable source but it claims the first Mersey Tunnel (the Queensway or Birkenhead Tunnel), opened in 1933, as the largest civil engineering project ever undertaken by a local authority. Its construction was driven (with the County Borough of Birkenhead in tow) by the Corporation of Liverpool and one of the most ambitious City Engineers in the country, John Brodie. We’ll give credit too to the consulting engineer, Sir Basil Mott and the architect Herbert James Rowse who designed the most visually striking elements of the tunnel, its ventilation shafts. Here’s the one on the Birkenhead side.

Ventilation shaft, Queensway Tunnel

The Kingsway Tunnel (to Wallasey) was opened – by the Queen again! – in 1971. I won’t force a municipal connection here – it was built by civil engineers Edmund Nuttall Limited but I know that the fans of Brutalism who follow this blog really like the ventilation shafts of this one too. To the left here in Seacombe is Mersey Court, a council block built in the mid-60s.

Ventilation shaft, Kingsway Tunnel

Just to the north, you’ll get the best view of the magnificent Wallasey Town Hall, designed by Briggs, Wolstenholme & Thornely – free Neo-Grecian in a Beaux Art tradition according to its Grade II listing. Begun in 1914, it was used as a military hospital during the war and was finally opened for municipal purposes in 1920.

Wallasey Town Hall

Travelling from the Seacombe to the Woodside Pier Head, the latter gives you a glimpse of Birkenhead Town Hall, opened in 1882 from a design by local architect Christopher Ellison. You’ll need to walk to the Georgian and Victorian Hamilton Square to see its Grade II* grandeur properly. It was used as municipal offices to the early 1990s and I visited it later when it was the Wirral Museum. Now it’s closed and awaiting a new role. I hope something fitting is secured.

Woodside Pier Head with the former Birkenhead Town Hall to the rear

Back to Liverpool and the waterside view of Liverpool’s crowning glory, not municipal but unmissable – the Three Graces: the Royal Liver Building, the Cunard Building and the Port of Liverpool Building. They’re maybe the reason that my wife’s ancestors thought that the ticket they’d bought to New York was genuine. In the end, they made a good life in Liverpool. Towards the right of this picture taken from the Museum of Liverpool, you’ll see the ventilation shaft of the Liverpool end of the Queensway Tunnel, not looking a bit out of place.

The ‘Three Graces’

Liverpool 8, Toxteth, famous for the riots of 1981, may still evoke very different images of the city. In fact, the taxi-driver who dropped us off in the district asked if we were sure that’s where we wanted to be – ‘they’re tough as old boots round here’ was his parting shot. That was undeserved, unfair to its poorer residents (he didn’t mean it kindly) and ignorant of just what a mix the area contains – some of Liverpool’s finest Victorian housing, some of its humblest, and a couple of wonderful municipal parks.

We alighted in Granby Street and walked down to what is now known as the Granby Four Streets area. I won’t begin to try to tell its story here – from good, solid Victorian housing to economic decline and dereliction, to the point when it seemed likely to be cleared as part of New Labour’s ill-judged Housing Market Renewal Pathfinder Programme, to the residents’ fight-back and the formation in 2011 of the Granby Four Streets Community Land Trust. Ronnie Hughes has been intimately involved with much of this and you should read his A Sense of Place blog to learn more.

Renovated homes in Cairns Street

Awaiting renovation in Ducie Street

Now some of its houses have been beautifully renovated (with more to come) and famously the creative reconstruction work of the Assemble arts collective won it the Turner Prize in 2015.

The houses are next to Princes Park, designed by Joseph Paxton and James Pennethorne and opened as a private park in 1842 (Pennethorne also designed Victoria Park in East London) and acquired by Liverpool Corporation in 1918. There are some fine houses, formerly belonging to Liverpool’s well-to-do, nearby too though most of the terrace below in Belvidere Road has been converted to flats and is social rented. These juxtapositions are strong in Liverpool.

Belvidere Road

A short walk brought us to this house in Ullet Road, once the home of John Brodie. Is he the only municipal engineer to get a blue plaque? As the brains behind the Queensway Tunnel, the designer of the UK’s first ring road, its first intercity highway and – apparently his proudest achievement – the inventor of goal nets in football, he deserves one.

The former home of City Engineer, John Brodie, on Ullet Road

Down Linnet Lane at the edge of Sefton Park, you’ll see some dignified post-war council housing, notably Bloomfield Green, a scheme for elderly people which won a Civic Trust award in 1960.

Bloomfield Green

The 231 acre, Grade I-listed, Sefton Park was opened by the Corporation ‘for the health and enjoyment of the townspeople’ in 1872. This stunning photograph (from the Yo! Liverpool forum and used with permission) shows the beauty of the park and its urban setting. You’ll see some surviving, now refurbished, council tower blocks in Croxteth, built from the late 1950s around the perimeter.

Sefton Park (c) YO! Liverpool

That it was still providing for the ‘health and enjoyment’ of local people was obvious from the crowds in and around its most celebrated feature, the Palm House, opened in 1896, rescued from dereliction in the 1990s, and more recently more fully restored.

I’ve written more than intended and I haven’t even started on the housing history of the four lads from Liverpool who forever changed the world of popular music. That will be a bonus post coming soon.

Notes

I’ve added a few additional contemporary images of St Andrew’s Gardens and some historic images of other multi-storey flats schemes on my Tumblr page here.

For some lovely images of the St Andrew’s community in 1967 take a look at this page from the Streets of Liverpool website.