Tags

This is the 200th post on the blog. I’ll be participating this week in the ‘Architecture, Citizenship, Space: British Architecture from the 1920s to the 1970s‘ conference at Oxford Brookes University. For that reason, I hope you’ll forgive a repost – the first to date – of this piece on the Blackbird Leys Estate which seemed appropriate. Rosamund West, who contributed an earlier post on the blog, will be there too, speaking on ‘Replanning Communities through Architecture and Art: the post-war London County Council’.

Blackbird Leys, situated on the south-eastern periphery of Oxford, is to all appearances a pretty ordinary, not to say humdrum, council estate. But it’s achieved notoriety. Some of this is typical of unloved and maligned marginal estates throughout the country but it’s loomed larger in Blackbird Leys and came to a peak in 1991 when three days of rioting followed a police crackdown on joyriding.

Oxford’s history of town and gown disputation is well-known but the divisions within the city grew after William Morris built his first car in 1913. From those small beginnings emerged the Morris car factory in Cowley, employing some 20,000 people by the 1970s. Oxford acquired an industrial working class and had to deal with it.

Blackbird Leys was one response. The city’s population had grown massively in the interwar period and demand for housing was high – there were 5000 on the council waiting list in 1946 and Morris Cars were expanding. Council planners saw the ‘final solution’ to the housing shortage in the development of large estates on the eastern and south-eastern fringes of the city.

Planning permission was granted in 1953 on 260 acres of land then occupied by a sewage works and farm in Blackbird Leys for an estate of 2800 dwellings with a projected population of 10,000.

The first residents moved in to what was still essentially a building site in 1958. Work continued over several phases into the seventies when the original scheme was largely complete.

A further expansion took place with the development of the Greater Leys estate on adjoining land in the mid-1980s. Around 14,000 people live in the area now.

A few residents had moved from a slum clearance area in the city centre and some from temporary housing erected during the war. Most of the men worked in the car factory and around half the population in the sixties had moved from elsewhere – from Scotland and Ireland in large numbers and from elsewhere in England – for employment.

There were tensions here already that the estate itself did little to warrant. A local newspaper wrote that the (1):

unlit building sites, inadequate police supervision, parental apathy and the provision of a public house catering mainly for young people, has provided the perfect setting for the idle, the mischievous, and the more sinister night people.

Who were these ‘sinister night people’? They surely weren’t as exciting as they sound but the phrase gives an early indication of the power of the media to shape perceptions and spread alarm.

Some residents surveyed in Frances Reynolds’ extensive analysis of the estate resented the former slum dwellers:

I don’t like it up here getting all the tail end. It’s a disgusting place. Putting all the backend up here won’t give people like us a chance to make this a decent place to live.

But those who saw themselves as ‘respectable’ might be equally resented by others:

from the beginning the estate was associated with ‘foreign’ workers come to get rich at the factories, with large rough families, and to a lesser extent with slum clearance. It was never accepted as part of the city proper and its reputation began the downward spiral…

From the outset, Blackbird Leys carried a stigma and many of its people felt ignored or victimised in equal measure despite the fact that it was in these early years predominantly an estate of the skilled and employed working class.

One resident recalls (2):

There was this big problem of being labelled. People were not able to get credit and hire purchase if they said they came from Blackbird Leys. Even the vicar could not get a phone in without having to pay in advance. None of us knew why. It was a brand new estate with no past as far as we were concerned. People working at the car works were among the best paid manual workers in Oxford.

That was Carole Roberts who had moved to the estate aged 14 from London when her father found work in the car factory. She went on to become a Labour Lord Mayor of Oxford but Blackbird Leys would remain her home.

The outstanding feature of the new estate, however, was its demography. It was built for families and in the sixties one quarter of its population was under five years of age, another quarter of school age. There were a lot of kids on the estate and later a lot of teenagers.

As to the design of the estate, in a word, it’s unexceptional – which points to both its good and bad aspects. It was solid, slightly ‘boxy’ housing – good accommodation in and of itself though space standards fell in later years.

Two fifteen-storey tower blocks with four two-bedroom flats on each floor were opened in 1960s. The Conservative mayor of Oxford who opened Windrush Tower in 1962 described the building as ‘modern living at its best’. But it wasn’t long before the common problems of lack of play space for younger children, lifts breaking down and vandalism of communal areas were being reported.

Housing density was relatively high and many complained about poor noise insulation.

According to one resident:

They put you all so close together yet it’s a big estate. I can’t explain it. My neighbours are friendly and yet it’s not a friendly place. I think it’s because we’re all so close together that there’s always somebody doing something to annoy you, if it’s only music, or lighting a bonfire, or mending a car, it’s because we’re all packed together.

The quote also points beyond straightforward design failings to what sociologists have termed ‘neighbourhood sensitivity’ – a reduced tolerance to the behaviour of others reflecting social differences within the community.

Blackbird Leys – despite the easy stereotype of council estates – was not homogeneous. The divisions which existed between ‘rough’ and ‘respectable’ residents, between owner occupiers (already 20 per cent by 1981) and council tenants, and between those of different backgrounds – though ethnicity itself was never a significant flashpoint – reduced tolerance of behaviours beyond the observer’s norm.

The estate was provided open space – particularly in the cul-de-sacs which were built in the early sixties – and later a large recreation ground but these were often not seen as ‘safe’ areas for younger children or inviting areas more generally. A single large community centre was provided but community amenities as a whole were thin on the ground. [I have added a response to this post by a resident of Blackbird Leys in the comments below which speaks positively of both the planning of the Estate and its current community spirit.]

Each of these elements are the quite normal features and failings of estates designed in the post-war rush to build – and build economically. But they came together in Blackbird Leys in peculiarly combustible form. The final piece in the jigsaw came in the estate’s changing demographics.

The 1977 Housing (Homeless Persons) Act – alongside the unanticipated impact of Mrs Thatcher’s right to buy legislation and the halting of council new-build – ensured that ‘vulnerable’ tenants came to form a large part of new tenancies. This trend was strengthened by the reality that such tenants –in urgent need of housing – were far more likely to be housed in less popular estates with a more rapid turnover of occupants such as Blackbird Leys.

At the same time the eighties’ collapse of the manufacturing economy hit the estate’s economic mainstay. By the early eighties, the proportion of male heads of household classified as ‘skilled’ had fallen from half to little over a third. In the same period, the rate of unemployment on the estate peaked at 20 per cent and 50 per cent for those aged 16 to 19.

Statistics indicate that by this time Blackbird Leys was a ‘problem’ estate with more than its fair share of ‘problem’ families. To select just a couple of examples, the estate contained 15 per cent of the city’s children and 30 per cent of those under social services supervision; it contained 17 per cent of juveniles (aged 10 to 16) but 27 per cent of those prosecuted for crime.

Of course, such figures are not ‘innocent’. Residents felt unfairly labelled and ‘picked on’ by the agencies of the state. The estate’s reputation may also have highlighted problems which were contained or treated differently elsewhere. Still, the sociological fine-tuning didn’t alter the lived reality of an estate seen by outsiders – and, increasingly, by its own residents – as crime-ridden and dysfunctional. The residents’ reporting of their own experience of crime or troublesome neighbours confirms this truth even if it’s understood as a complex one.

All this came to a head in September 1991. ‘Hotting’ – the theft of cars followed by displays of driving prowess on the estate’s streets – had become a local sport for some of Blackbird Leys’ youngsters. A police crackdown was met by resistance when up to 150 youths stoned riot-geared police officers.

All this came to a head in September 1991. ‘Hotting’ – the theft of cars followed by displays of driving prowess on the estate’s streets – had become a local sport for some of Blackbird Leys’ youngsters. A police crackdown was met by resistance when up to 150 youths stoned riot-geared police officers.

An academic analysis describing such activity as ‘carnivalesque’ is probably designed to enrage Daily Mail readers but the pleasure and meaning of it for participants – in its thrill-seeking and oppositional nature – should be understood.(3) It was correct to blame media attention – some spoke more darkly of media incitement – for giving a distorted picture of the estate but clearly something had gone wrong. These marginalised youth on a marginal estate were expressing something, however inchoately.

Another, very different, expression of the local community’s disaffection with the powers-that-be came in 2002 with the election of an Independent Working Class Association (IWCA) councillor, defeating Labour, for the estate. At peak, the IWCA returned four local representatives. The IWCA stood on an unashamedly populist platform which stressed New Labour’s abandonment of its class loyalties and called for local action against crime and drug-dealing – against those seen as ‘lumpen’ elements of the local proletariat.

All in all, this seems less a municipal dream, more a municipal nightmare. What more needs to be said?

Well, this for a start, though perhaps it comes too late to challenge all the negatives – two thirds of residents in Reynolds’ survey liked the estate and had no intention of moving. These contented residents reported they were happy with their homes, their neighbours and neighbourhoods and local facilities. They were also more likely to have relatives living on the estate.

Mrs Knight, 79 years old, got on well with the local children:

They’re ever so friendly. They call out Hello Nellie when I’m in the street. They’re never any trouble. It’s a wonderful place…

A few years later perhaps some of them were stoning the police.

Just last year, a resident who had lived on the estate for 51 years stated (4):

I love it here, even if I won the lottery I wouldn’t move. The area is peaceful, it’s lovely and all the neighbours get on with each other, it’s that community spirit. Blackbird Leys has so many facilities for children and adults and there’s a lot to do if you are prepared to go ahead and find it.

I don’t claim that these views are representative but they do add nuance. Council estates are not just bricks and mortar; they reflect complex human dynamics within and the impact of – often very difficult and damaging – political and economic currents without.

Blackbird Leys remains a significantly deprived area: in 2010 Northfield Brook ward was amongst the 10 per cent most deprived in the country – a long way from the ‘dreaming spires’, a marginal estate in every sense of the word.(5)

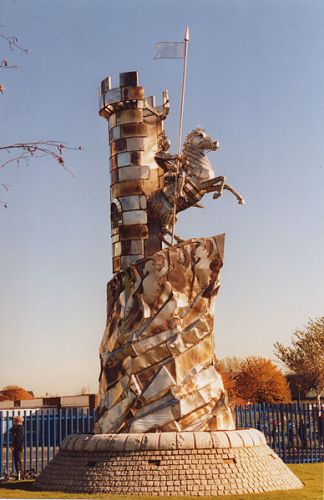

The Glow Tree which evolved out of a community arts project was unveiled outside the Blackbird Leys Community Centre in 2006.

But Blackbird Leys has always had a community which has survived its problems and battled the stereotypes. That community exists today in its homes and streets and, semi-officially, in that complex nexus of self-help and state-sponsored regeneration which has emerged since 1997. Crime has fallen drastically, new facilities have been built, black spots eradicated – much has been done (too much according to some disgruntled Oxford residents who feel Blackbird Leys has been singled out for favourable attention) and much remains to be done.

If that seems an anodyne conclusion maybe it’s the only one that captures the past and present contradictions of the estate’s story: never the New Jerusalem, nor ever the Hell on Earth that many portrayed.

Sources:

(1) This quote and unattributed quotes that follow are taken from Frances Reynolds, The Problem Housing Estate. An account of Omega and its people (1986) – Omega was the name Reynolds gave the estate to preserve its anonymity.

(2) Quoted in ‘We’re proud of our estate‘, Oxford Mail, 27 November 1998

(3) Mike Presdee, Cultural Criminology and the Carnival of Crime (2000)

(4) Quoted in ‘Project unveils history of Blackbird Leys‘, Oxford Mail, 9 March 2012

(5) Oxford Safer Communities Partnership, The Indices of Deprivation, 2010: Oxford Results

BBC Oxford has pages on the Development of Blackbird Leys and the ‘Community Troubles‘ of 1991. The stills of ‘hotting’ and rioting above are taken from the latter.