We left Castle Vale last week, an undoubtedly troubled estate, damaged by the construction flaws specific to much system-built housing of the sixties and beset by the social problems affecting estates across the country as a traditional working-class economy collapsed and council housing itself became increasingly allocated to the most vulnerable of our community.

Castle Vale, 2004. Compare to the similar aerial view taken in 1993 in last week’s post (c) Mornement, No Longer Notorious

Something needed to be done but hostile central government attitudes and policy – notably Right to Buy and the deadly squeeze on new housing investment – ensured (quite deliberately) that local government was in no position to do it. Thatcherism was hostile both to council housing and the (predominantly Labour) authorities which still managed it. Conversely, the 1988 Housing Act had established privately managed and well-funded Housing Action Trusts (HATs) to regenerate some of the country’s ‘worst’ estates. It’s not difficult to read the political agenda here.

The estate from one of the Farnborough Road towers in the 1960s (c) Mornement, No Longer Notorious

Birmingham’s Director of Housing, Derek Waddington, was authorised to discreetly investigate what was happening on the North Hull Estate, the first HAT in the country. Though some Labour councils and tenants (such as those in Hulme, Manchester) resisted this apparent privatisation of assets and homes, the pragmatic case for following suit seemed unassailable. As Waddington describes: (1)

Eventually I had to stand in front of the Labour group and tell them the professional facts. And then I left the council chamber and they sorted out the political elements. In the end they accepted it. For this one simple reason…the Government quango gets direct gift money up front to plough in the infrastructure.

Political backing from the Council and central government and a twelve-month campaign in favour was enough to ensure that 92 per cent of tenants voted to transfer to the HAT on a turnout of 75 per cent.

The Castle Vale HAT was established in June 1993. After some wrangling, it secured greater tenant representation (the management board eventually comprised four residents, three local authority representatives and five independents) and government funding of £160m.

Chivenor House and school, 1960s

The first priority was to tackle the estate’s housing problems – the 1994 Masterplan proposed demolishing seventeen of the estate’s 34 tower blocks. In the end, it was determined that costs outweighed the benefits of refurbishing fifteen further blocks. Currently just two remain – Chivenor House (now housing for the elderly) and Topcliffe House; both were attached to schools which would also had to have been demolished. Twenty-four system-built and flawed four-storey maisonette blocks were also cleared. In their place, 1458 new homes have been built and 1381 refurbished.

The new housing reflected the changed sensibilities of its time. The sheltered housing scheme, Phoenix Court, built on the site of the Centre 8 blocks won a Secured by Design award from the police. Twenty-eight ‘Reinventing the Home’ family houses were built by the Mercian Housing Association on Cadbury Drive, designed to adapt to changing domestic needs. There are small pockets of self-build and ‘eco-homes’ too. Some of the new build looks fashionably gaudy; most of it safely suburban.

Chivenor House today

Though, as I write, ‘regeneration’ threatens good (and sometimes expensively renovated) housing and solid communities across the country, there seems no real need here to lament the loss of these particular blocks which were clearly poorly built from the outset. But, then as now, ‘regeneration’ is accompanied by a host of attitudes and policies which should be questioned.

For one, there was now the familiar emphasis on the importance of tenure mix. As often as not, this is now a means of generating income in a world in which the market rules and traditional and highly cost-effective means of investment – in other words, public loans which were repaid (with the benefit of both providing genuinely affordable housing and lasting community assets) within thirty years or so – are deemed unacceptable. But there is also the assumption that estates themselves were a flawed social model, that ‘successful’ communities require higher levels of owner occupation and injections of middle-class affluence and aspiration.

Demolition of Castle 8 blocks, 1996 (c) Mornement, No Longer Notorious

It’s worth pointing out that council estates were once both a site and symbol of working-class affluence and aspiration and that – before they were deliberately designated as housing of last resort – they did contain a social mix. Furthermore, on Castle Vale itself almost one in three homes had been built for owner occupation. Still, the HAT instituted a Tenant Incentive Scheme in 1997 which offered a £10,000 grant to existing tenants to purchase their home. By 2004, owner occupation on the estate had reached 39 per cent (from 29 per cent in the 1990s).

1997 takes us back to the New Labour era and its slogan, espoused by Tony Blair, that his government would be ‘tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’. Not too many speak up for New Labour nowadays but again, in the interests of balance, it should be pointed out that criminality and antisocial behaviour were problems which hurt, disproportionately, still overwhelmingly ‘respectable’ working-class communities.

The Trees pub prior to demolition (c) Valeboy and the Birmingham History Forum

All five existing pubs – which ‘had long been dominated by drug dealers and criminals’ according to the HAT – were demolished. The HAT (as did some local authorities) also adopted toughened tenancy regulations which eased the eviction of households considered to cause nuisance. Members of the so-called and locally notorious Green Box Gang were evicted in 1998. Further evictions followed. Tough police action, in cooperation with ValeWatch (a joint police-HAT initiative), directed against drug dealing and gangs also followed and, of course, lots of CCTV. Although crime rates didn’t start falling until 2000, it all seems a strong fulfilment of the New Labour mantra.

Refurbished housing (c) Mornement, No Longer Notorious

The great claim made by the HAT programme is that it tackled problems holistically by recognising that social, economic and physical problems were related. Not a unique or searing insight perhaps but one that Castle Vale HAT practised at least by a concerted programme of interventions tackling, for example, employment. I won’t list the various schemes here (read No Longer Notorious, linked to below, for the HAT’s own celebration of its record) but by 2005 unemployment on the estate had fallen to 5.3 per cent – below the Birmingham average of 7.6 (though the fall in the latter suggests that the HAT can’t take all the credit). (2)

New housing (c) Mornement, No Longer Notorious

Health, rightly, given that life expectancy in Castle Vale was eight years below the national average, was another focus. In fact, the estate had been an early pioneer of integrated healthcare with its doctors, midwives, social workers, and health visitors all based in the same building from the 1960s. But a comprehensive 1992 survey paved the way for a wide-ranging set of initiatives to tackle the estate’s particular problems of alcohol and drug abuse, infant mortality, domestic violence and mental illness. The Sanctuary, a model of one-stop multi-agency working, was opened in the heart of the estate in 1991. Life expectancy has increased by seven years.

The Sanctuary (c) Mornement, No Longer Notorious

It’s hard to challenge such an apparently unalloyed good news story and why would you want to unless you’re a committed municipal curmudgeon like myself but it’s an undeniable and self-confessed fact that the HAT worked very hard on public relations. As Angus Kennedy, Chief Executive of the HAT stated:

Image management is as important as physical improvements. If we can’t attract people to an area, then it doesn’t have a sustainable future.

Positive publicity featured in Mornement, No Longer Notorious

From 1996, Castle Vale HAT employed a full-time PR officer with an assistant and a £100,000 budget. He or she worked well, perhaps with good material. Positive press stories increased from 29 per cent in 1979-1981 to 93 per cent in 2000. In 2001 the HAT began to develop its own ‘image management strategy…driven by a baseline study conducted by MORI’. (3)

It’s easy to be cynical about some of this, to think at least that all this effort could be better directed towards concrete improvements rather than communications flimflam and yet perception, if not all, has enormous impact on reputation and well-being – as many housing estates can testify. We saw this recently when we looked at North Shields’ Meadow Well Estate. A study of both estates demonstrated how ‘a problem reputation can reinforce or even magnify an estate’s material difficulties’. (4)

We’ll make some allowances here then (whilst looking at some opposing views) – just imagine how council housing might have fared if it hadn’t been subject to such relentless press negativity in recent decades.

Then, of course, we lived in the era of ‘private sector good, public sector bad’ (a perception that I’d like to think might have shifted more recently). Given that, it’s no surprise that a new shopping centre and particularly the opening of a new Sainsbury’s as its anchor in July 2000, was heralded by the Progressive Conservatism Project as having a ‘profound and important effect on morale and confidence’ in Castle Vale, previously a ‘brand desert’. (5)

Castle Vale shopping precinct, 1994 (c) Mornement, No Longer Victorious

All this allowed one journalist to gush in 2003: (6)

These once bleak streets are now lined with attractive new houses and mews flats, piazzas and courtyards, travel agents and delicatessen counters, a new football stadium and a thriving college for the performing arts.

According to Adam Mornement, ‘the forgotten wasteland populated by towers had become a dignified low-rise estate’.

Whatever the reality – and I suspect that Castle Vale remains grittier than that language implies – the whiff of gentrification is plain to see. And not everybody embraced the changes. There was significant resistance to the HAT in its early years from the Tenants’ Forum who felt a loss of democratic control and ownership – one protest featured ‘You’ve Been Quangoed’ tee-shirts to make the point. The HAT records this as a heeded reminder of the need to strengthen consultative processes. (7)

Looking back, a correspondent on the Birmingham History Forum regrets ‘all the green space, swallowed by the new housing, the Park Lane fields just across the railway…now an industrial complex’. (8)

For a real alternative perspective, read the anonymous (though perhaps not representative) comment on a laudatory article in a June 2013 edition of the Tyburn Mail: (9)

Let’s celebrate Castle Vale that may have needed work and tlc but ended up having everything taken away and replaced by things chosen by a certain few. Castle Vale went from a bustling busy estate to a dull and miserable former shadow of itself. Well done to the money men is all I can say – you spent little, pocketed lots, and left!

Others have criticised the quality of the refurbishment which has taken place. (9)

Still, it’s clear that most residents, old and new, have welcomed the changes and the positive improvements which have taken place. A police officer who worked on the estate in the 1970s and 80s considers that the HAT ‘worked a miracle…the place now is a lot better than it ever was’.

The HAT was wound up in 2003. A ballot of the HAT’s 1327 tenants that year voted by 98 per cent to transfer housing management to the Castle Vale Community Housing Association set up in 1997. I’ll confess a sneaking admiration, though, for the 18 tenants who opted to return to Birmingham City Council control (and perhaps got better tenancy conditions as a result).

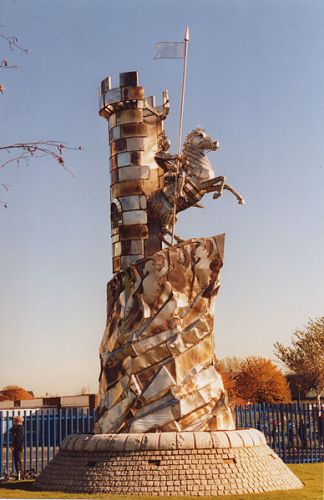

John McKenna, ‘Knight of Castlevale’, 2002 (c) Wikimedia Commons

Castle Vale is held up as the great Housing Action Trust success story and taken by many to symbolise what ‘good’ regeneration can achieve, particularly when freed from the ‘dead hand’ of local authority control. I think you could read this post and draw that lesson.

Or you could draw another lesson. Estimates vary but it’s probable that (to 2005) the estate’s regeneration cost £318m – £205m from public funds and £113m, ‘leveraged’ in, principally from the private sector. Imagine if local government had that money to spend and a similar freedom to build, rebuild and act – democratically and ‘holistically’ – to defend and support its community.

Sources

(1) Quoted in Phil Ian Jones, ‘The Rise and Fall of The Multi-Storey Ideal: Public Sector High-Rise Housing in Britain 1945-2002, with Special Reference to Birmingham’, PhD thesis, School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Birmingham, 2003.

(2) Adam Mornement, No Longer Notorious – the Revival of Castle Vale, 1993-2005 (Castle Vale Housing Action Trust, 2005)

(3) Alison Benjamin, ‘Putting the record straight’, Roof, November/December 2000

(4) Jo Dean and Annette Hastings, Challenging images. Housing estates, stigma and regeneration. The Policy Press and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation 2000

(5) Max Wind-Cowie, Civic Streets: the Big Society in Action (Progressive Conservatism Project, Demos, 2010)

(6) Helen George, ‘New Castle’, Housing (magazine of CIH), February 2003

(7) Mornement, No Longer Notorious

(8) ‘Valeboy’, comment in Birmingham History Forum, October 21st, 2012. The comment from the police officer below is taken from the same source.

(9) The extended comment is even more trenchant and has much more to say. See ‘Castle Vale plans Year of Celebration: 20 years of regeneration for an estate that should be proud of its democracy’, Tyburn Mail, June 17, 2013

(10) Patrick Burns, ‘Midlands: On the Vale’, BBC West Midlands, 4 March 2005

Pingback: The Castle Vale Estate, Birmingham, Part I: ‘Utopia’ to ‘civic pigsty’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Castle Vale Estate, Birmingham, Part II: ‘a dignified low-rise estate’ — Municipal Dreams | Old School Garden

Yet another interesting andt thought-provoking article. Thank you,whoever you are.

Very interesting. Just a minor point but the first article seemed to suggest that there was a swimming pool on the estate from its inception. This was not the case. We had to travel to Nechells for school swimming lessons. A campaign to get a pool was long running. It still hadn’t happened when I left Birmingham in 1981.