Tags

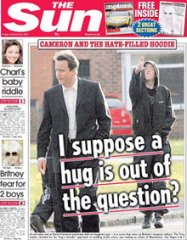

Back in 2007, the Wythenshawe Estate became the poster child for ‘Broken Britain’. David Cameron had visited the estate to make his call to ‘hug a hoodie’. But whatever love Cameron was offering didn’t appear to be reciprocated.

It was ironic that Wythenshawe should be singled out in this way, tragic that the ideals and vision which had built the estate had been so signally eclipsed.

Lest we forget, the story begins with a level of overcrowding and human misery that is – thankfully – almost unimaginable in Britain today. In 1935, Manchester’s Medical Officer of Health condemned 30,000 (of a total of 80,000) inner-city homes as unfit for human habitation; 7000 families were living in single rooms.

In contrast, it was the garden city movement of Ebenezer Howard which provided the other major element in Wythenshawe’s genesis. Howard and his followers advocated a utopian ideal of economically self-sufficient communities, cottage dwellings in parkland surroundings – the polar opposite of the Broken Britain of that day.

In contrast, it was the garden city movement of Ebenezer Howard which provided the other major element in Wythenshawe’s genesis. Howard and his followers advocated a utopian ideal of economically self-sufficient communities, cottage dwellings in parkland surroundings – the polar opposite of the Broken Britain of that day.

In Manchester, these currents coalesced in the drive and vision of three people: Labour alderman WT Jackson and then Liberal husband and wife team, Ernest and Shena Simon.

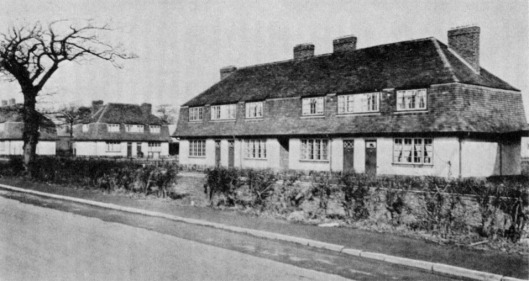

Jackson rejected the modernism that attracted some as a solution to the slum problem: ‘We are not emulating Vienna and I have not been there…In general we favour the cottage type of dwelling’. For Ernest Simon ‘the tendency of country conditions [was] to preserve life…the tendency of town conditions [was] to depress vitality’. The solution they envisaged lay in large-scale development of agricultural land to the south of Manchester beyond the city boundaries.

Simon purchased Wythenshawe Hall and 250 acres of land in 1926. He donated them to the city, directing only that they ‘be used solely for the public good’.

Jackson for his part persuaded the city to buy 2500 acres of surrounding farmland in the same year and secured the incorporation of the future estate within city boundaries – against horrified opposition from Cheshire locals – in 1931 by private act of parliament.

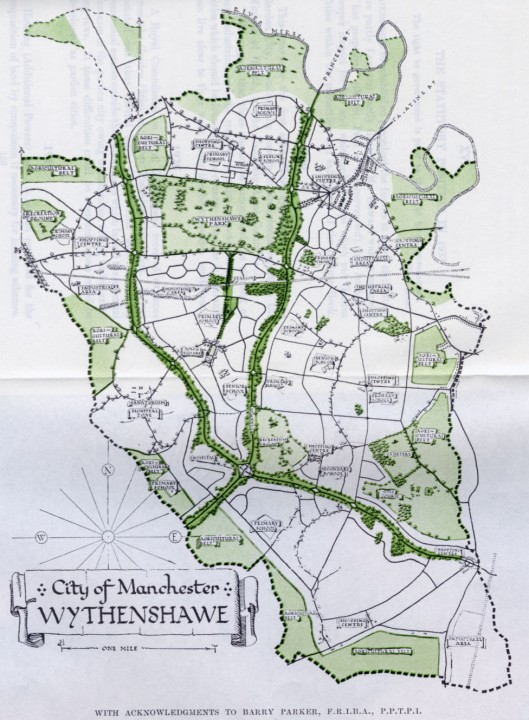

Jackson visited the garden city showpiece of Letchworth in 1927 and brought in Barry Parker – its co-designer – as planner of the new Wythenshawe Estate. Building began the same year. Parker was given sole control of the project in 1931.  Parker built on the garden city ideal by adding two new features.

Parker built on the garden city ideal by adding two new features.

One was the parkway – a concept borrowed from the more motorised America of the day – intended to smooth transit but, more importantly, to prevent ribbon development and preserve open space. The scenic route Parker created – the Princess Parkway – is now the M56. Perhaps not quite what he had in mind.

His second innovation was neighbourhood units set around green spaces and tree-lined roads with, in this instance, Wythenshawe Hall and Park preserved at their centre. This principle has been better honoured – some 30 areas of park and woodland remain.

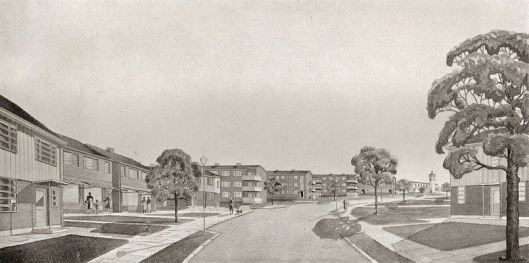

Development was rapid. By 1939, the estate boasted a population of 40,000 and some 8145 dwellings, now described waspishly in Pevsner as ‘conventional, Quakerishly undecorated’. Parker was a Quaker so this plain and simple approach reflected his ideals but it fulfilled more strongly Shena Simon’s wish that the estate have a ‘cottagey’ feel.

If the housing was modest, the ambition which underlay the project wasn’t. For Shena Simon, the estate was the ‘boldest [scheme] that any municipality has yet embarked upon’. To the local Cooperative Women’s Guild, it was nothing less than (1):

the world of the future – a world where men and women workers shall be decently housed and served, where the health and safety of little children are of paramount importance, and where work and leisure may be enjoyed to the full.

This future world was a place in which ‘every working mother [would enjoy] a clean, well-planned home which will be her palace’. If this seems a stereotyped view of a woman’s role today, let’s note their rider: these were homes ‘so well and wisely planned that [a mother’s] labour will be lightened and her strength and intelligence reserved for wider interests’.

Who got to enjoy this brave new world? Rents were typically between 13s and 15s a week (65 to 75p) at a time when the average working wage stood at around £3. Ernest Simon calculated this was just affordable – provided there was a ‘willingness of the wage earner to be content with a very small amount of pocket money, and competent and economical management on the part of the housewife’.

In reality, the estate was principally confined to the better-off working class as this oral testimony suggests (2):

Not everyone could get a house in Wythenshawe. Before we got one an official from the Town Hall wanted to know all about us…We had to prove we were good tenants. We…heard that some people were from the slums but we never met any of them.

Despite – more probably because of – this exclusivity, there was great pride in the estate. Local activists were committed to making ‘Wythenshawe worthy of the time and money spend on it’. A ‘Wythenshawe ethos’ grew which enjoined a ‘common bond’ predicated less on shared recreation than on notions of self-improvement.

As with Becontree (see my previous posting on that London County Council estate), gardening was a particular locus of this and the annual flower and vegetable show an important event in the local calendar.

Piper Hill Avenue, Northenden 2012 © Gene Hunt, licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons licence

Many residents also spoke favourably of a world where people weren’t forever popping round for a chat or – worse still – on the cadge, ‘where people kept themselves to themselves’. All this has upset some later commentators who see in it some corruption of working-class community and ideals. But maybe we shouldn’t pay too much heed to this liberal academic nostalgia for a world they never knew and tend now to romanticise.

That there was a shift – to a more privatised and domesticated focus on family and home – is undeniable. But I see it less an example of malign social engineering or embourgeoisification, more as an opportunity working people desired and acted upon, one that – in key ways – they created.

Practically, as so often, execution failed to fully match conception. Shops, community facilities and employment followed belatedly on housing and population growth. There was an incomplete and dormitory feel to the estate in its early decades though the Second World War and 1947 Town and Country Planning Act were to give a boost to further ambitious growth. New industrial zones were completed in 1950s. Higher density housing was planned and built. The population grew to 100,000.

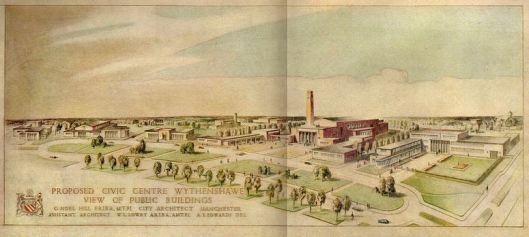

The shopping centre – confusingly called the Civic Centre – was finished in the 1960s. An actual civic centre – the Wythenshawe Forum incorporating leisure centre, library, theatre and meeting rooms – was finally opened in 1971.

Wythenshawe Civic Centre – the flats at the top were demolished in 2007 and replaced with a local authority ‘services hub’ © Wikimedia Commons

By the turn of the century the Wythenshawe infrastructure was largely in place. So what went wrong? In the aftermath of the hoodie affair, a New York Times journalist, visiting the ‘endless housing project’ of Wythenshawe (’pronounced WITH-en-shah’ she added helpfully), noted bleakly ‘the absent fathers, the mothers on welfare, the drugs, the arrests, the incarcerations, the wearying inevitability of it all’. (3)

And it’s true that levels of deprivation on the estate were significantly higher than the Manchester average, twice as high as the national average. In 2000 Benchill was named the most deprived council ward in England.

This doesn’t seem to me to reflect some original sin in the conception or design of council estates. Rather it speaks of crushing realities that would hobble the ideals and potential of any community. Criticisms of estates as single-class and socially isolated have merit but they lack historical perspective – specifically an understanding of the ‘respectable’ and aspirational foundations of social housing and the massive demographic shift that has hit it since the 1980s.

Council estates, which were once a symbol – a site, in fact – of upward mobility, now represent downward mobility or social stasis; this reflecting not some moral failing on the part of social housing’s poorer tenants but the hard fact of economic changes that have all but destroyed traditional working-class livelihoods.

The new Woodhouse Park Lifestyle Centre opened in 2006 © Copyright Anthony O’Neil, licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons Licence

However, this depressing perspective should not be the final word. There has been huge investment in Wythenshawe in recent years. The shopping centre was substantially renovated between 1999 and 2002. (In a sign of the times an Asda store with multi-storey car park replaced the old Coop.) £18m has been spent on the Wythenshawe Forum to modernise and extend its facilities which now include additionally an adult learning centre, nursery, café and health centre.

A lot has been done by central and local government and community organisations and activists to shift realities and – perhaps almost as importantly – perceptions. There’s no need to sugar-coat here: significant and real problems remain but the estate deserves to be more than a caricature. And the ideals which inspired it should be valued, maintained and fulfilled.

Sources:

(1) This and most of the foregoing quotes are taken from Andrew Davies, Workers’ Worlds: Cultures and Communities in Manchester and Salford, 1880-1939 (1992)

(2) Quoted in John J. Parkinson-Bailey, Manchester, an Architectural History (2000)

(3) Sarah Lyell, ‘How the Poor Measure Poverty in Britain…‘. New York Times, 10 March 2007

Pagan555’s Wythenshawe images can be found in his Flikr photostream and are used with his permission.

Andrew Davies, cited above, offers an excellent social history of the estate.

Articles by David Ward and Owen Hatherley in The Guardian provide some contemporary views and this article by Mark Hughes in The Independent will update you on the young man greeting Mr Cameron in the opening image.

Improved a lot wythenshawe agreed ! But still a massive shithole and another generation of even bigger wankers and robbers and now the bedroom tax and universal credit coming into play watch the crime rate hit the roof and deprevation go up !

Tough times. Sorry to hear things seem as bad as you say but I appreciate you taking the time to comment.

The only thing that makes or breaks a neighborhood are the people in it. I grew up there in the 1950’s when the overall quality of the residents was superior. Better manners, better. Behaved, more considerate of others, better understanding of right and wrong, and before the idiot politicians canceled the call up. Back a few times, very saddened at what I saw in my old neighourhood

I agree with you for the most part, but it only applies to certain parts of Wythenshawe. With the pressure on housing, there has actually been a process of gentrification in certain parts. Most of the remaining farms and market gardens have been turned over to private housing, which is a shame, but people have to live somewhere. The bad behaviour people talk about is often down to just a few families that are out of control. However, if people think Benchill is bad, try Hattersley or the Langley estate near Rochdale. Wythenshawe is probably the best Manchester overspill estate.

Pingback: The Wilson Grove Estate, Bermondsey: ‘A cottage home for every family’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Downham Estate, Lewisham: ‘the joy of having your own patch’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Flower Estate, Sheffield: ‘dainty villas for well-paid artisans’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Local government…the first-line defence thrown up by the community against our common enemies’ | Municipal Dreams

yes it is full of wankers robbers and huddys ……. but that’s Stereo typeing not everyone in Wythenshawe is a degenarate

Wythenshawe hasn’t improved, it’s only asset, open green spaces, have been removed.

Total mis-management from all the authorities, in particular , Willow Park.

Shameful a decisions from Manchester council, selling off all the school fields to privateers !

Kids in ‘Wivvy’ have never had it so bad!

I’ll take that comment from someone who knows the area a lot better than I do. Very sad to hear that the green open spaces – which were one of the big plus points of the original scheme – are being lost.

What is particularly galling is that the local housing authorities continue to use the ‘Garden City’ sobriquet, when it’s they that have removed living hedgerows,tarmacked gardens and built on every open space and demolished the original schools.

Corporate vandalism, destroyers of ideals !

Ive lived in Wythenshawe all my life and sometimes am proud some times am ashamed to say its where iam from,we have had a fair bit of bad press over many years.There is much improvement on the estate from the run down flats that once where, but it seems to me the only reason for the regeneration of the area is to make the place look and sound better for investors encouraged to invest in the new Airport city.We see buildings knocked down then replaced,regenerated transport links(the tram) but the problems are still here, and in the begining we had everything we needed such as local shops,parks,lesuire centers ect.So why did the creation of this beautiful garden city go wrong? We have lost alot of our green space to development and office buildings which are now stood empty waiting to be let,and the green space we do have is not being looked after.The hall of Wythenshawe donated to the people is struggling to survive and another peice of our heritage Baguley hall stands empty and unused.I feel the problem lies with society, people used to be proud of where they lived and everyone looked after the area.This is not the case for many people now, in many areas not just wythenshawe.Mabie boot camp for the people who are not getting the correct upbringing would help because prison is not the answer. Its hard to find answers to the problems with society,but a social divide is not the answer

there was a time when people helped each other because everyone was in the same boat,mabie consumerism is the problem and the want for more and better things.

Who knows what the answers are? but one thing i do know is Wythenshawe has some great people born and bread and if we can turn the bad reports into positive ones then the ideas of the garden city did work.

Donna,

Thanks so much for taking to time to comment on my post and it’s always great to hear from someone with personal experience – and affection – for the places I write about.

You’re the second person to write about the loss of open space. Ironic because that was such a great thing about the estate in its heyday.

I can understand how you feel about regeneration too which often doesn’t seem to do much for the people that actually live in the area.

I don’t have answers either, I’m afraid, but society and the economy have changed so much since Wythenshawe was built and I guess you just don’t have the stable community it was built for.

All the best, MD

I was born in Wythenshawe in 1958 in a council house with a lovely corner garden which included a large oak tree. I was one of five children and my dad worked at Mr kiplings for over 25 years before working in Hulme in his father’s bookmakers shop. My mother worked part time doing cleaning, shop work and she also worked behind the bar at the horse and farrier pub in gatley. We bought a lot of our clothes from jumble sales (even our shoes sometimes). Even though my parents worked we were really quite poor. I have many happy childhood memories of spending time with my father at wythenshawe park, sharston baths and holly hedge park. I have only lived away from wythenshawe for a year and a half when I lived in a two up two down council house in longsight (with cockroaches) when I was first married. I exchanged back to wythenshawe to be near my family. There is some unemployment here but there are a lot of respectable people who have a work ethic and would rather do a job that is low paid and hard than expect tax payers to fund their existence. Unfortunately, there are some who need to be encouraged to get off their backsides. Hence the welfare reforms and spare room tax. If people don’t want to move from their larger than needed houses, unfortunately for them they will just have to get a job. I really enjoyed reading your article on wythenshawe. Some people don’t appreciate how lucky they are that they don’t have to live in one room with their whole family.

Thanks for your memories and comments, Pam – glad you enjoyed the post.

Total disagree with what Pam has said, council houses, that’s what they were, guaranteed homes for life, it’s the only security the poor had, Tory bastards removed that security, don’t be a victim of the poor hating media!

The housing issue is down to Thatchers idealism, selling off OUR homes, now many owned by exploiting private landlords, the Labour Party (joke) should compulsory purchase all ex council houses and take them back into council hands.

Tenants no longer feel that we own our estate, it’s run by privateers and profiteers, we have no say, outsiders have milked government investment to meet their own needs, nothing to do with our needs or wishes !

totally disagree with you pam and agree with everything andy is saying you sound like you have been sucked in by all the tory media rubbish and forgotten who and where you claim you are from..shame on you!

Really interesting article. I think with the various social problems Wythenshawe has it’s often overlooked what a positive housing solution Wythenshawe was at the time. Even now, it’s a better place than a lot of its equivalents elsewhere in the country – Easterhouse in Glasgow, Norris Green in Liverpool, etc.

Pingback: Municipal Housing in Manchester before 1914: tackling ‘the Unwholesome Dwellings and Surroundings of the People’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Hulme Crescents, Manchester: bringing ‘a touch of eighteenth century grace and dignity’ to municipal building | Municipal Dreams

That Wythenshawe has issues, cannot be denied.

But, there are many, many good people living and working in M22/M23… see here:

http://www.lift-offmagazine.co.uk/

Okay, the mag is not entirely focused on the area but, there are plenty of good news stories that the local press and the doom-and-gloom merchants choose to ignore – but that wouldn’t sit well with those who like to stereotype this part of Manchester as some sort of third-world enclave, would it?

Great piece, MDiH, thank you.

Pingback: The Dover House Estate, Putney: ‘Here comes Uniform Town’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Social Housing under Threat: Keep it ‘affordable, flourishing and fair’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Lillington Gardens Estate, Westminster: ‘civilizing, elegant and exciting’ | Municipal Dreams

i was born in gorton and moved to wythenshawe in 1952 it was bleak to start with but over many years it has improved ok a lot of green land has gone but we need progress to make a better life in 1952 working class did not have cars etc but people now have cars a lot of cars you need space to park etc stop moaning wythenshawe has every thing we need a world famous hospital . international airport . bus services trams . motorway network . industrial parks . wythenshawe i would not leave it for all the tea in china

Pingback: The Watling Estate, Burnt Oak: ‘Building the new England’ | Municipal Dreams

What a sad little person Andy is , When saint Thatcher gave the rite to buy she stopped the estate from total decay , the homes that were sold to the tenants didn’t disappear you clown , they are all here being mentioned and cared for by there owners . I am one of them , and I have to look at similar homes as mine that are a total disgrace , a lack of pride in wear they live .couldn’t care less about their gardens ,never clean there windows .park on the verges totally destroying the look of the area .

Andy if you require a lift to another county let me know I will gladly give you a lift .

Pingback: Right to beauty… | MS Ecology

wythenshawe is fast becoming a concret jungle instead of a garden city, every bit of greenery is being built on. with no where for familys to go with children to socialise, and building private houseing doesnt change an estates profile.

Pingback: The Speke Estate, Liverpool II: ‘Speke is not Sarajevo; Speke is quite a nice estate’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: St Luke The Physician – Benchill Manchester |

We moved to Wythenshawe in 1945 having lived in Hulme and our street being bombed We lived at the end of Woodhouse Lane Crossacrespadt the Smithy and the little Wooden Shops after our little road that was the end of the houses until Woodhouse Park started to be built. After our little road until the 50s was fields farms then the hangars that is now kown as Manchester Airport. We couldnt have grown up in a lovelier place. I still travel up there to see the changes and its so very different to bygone days I miss those days in Wythenshawe .

I agree wholeheartedly with you Maria, and I remember those little wooden shops and the smithy so well from when I dared to venture up there from further back along Woodhouse Lane as a kid. My family and I moved to Lyndene Road from Bradford (Manchester) in 1948 and it was so peaceful in comparison, and when all the days seems filled with sunlight and granny’s “Mrs Dale’s Diary” was on the wireless. :-) I look at Hollyhedge Road shops and around that area now – from the other side of the world on Google Street View – and I’m amazed at the changes over the years but I’m relieved to see Threadgold’s bike shop still survives! They’ve even got a tram line down the middle of the road I see.

I have to admit to being a wee bit sad at the apparent decline in friendliness between the residents of Benchill however, despite what the Authorities would no doubt claim to be improvements in local amenities.

Andy W.

Proud to be born & bred in Wythenshawe in 1955, have seen many changes over the years, some good & more bad. Heritage buildings gone such as Peel Hall, Knob Hall, Heyhead Village, cottages in the Grounds of what was Poundswick Grammer, The Cedars, Moss Farm, Woodhouse Farm. Civic Centre built, Greenbrow Parade gone, Minsterly Parade gone, Sharston Shops, Sharston Hall gone, several schools gone, Public Houses gone, Haverley Hey shops gone. Wythenshawe Hall neglected for over 30 years, full of rot, woodworm, pigeons & squirrels in the roof space, The South Lodge gone where they have the fair. One of the biggest problems is Councillors trying to get themselves a name at the expense of our estate, going to meetings, making decisions or agreeing to the like of Willow Park or St Modwins without telling any of the residents what they are meeting for, what they have agreed to on their behalf. A real big problem is the Airport, there seems to be no one to keep them in check, they just do what ever they want. Passengers cars parked both sides of some roads, that along with parents parking on pavements preventing prams/buggies or wheelchairs getting past & parking on grass verges making the place look a shoddy mess, they don’t care, they don’t live here near the school or the Airport. A Bye-Law is what is needed so people can be ticketed, put the money towards the majority from the Airport for Jobs keeping the place tidy. Cutting grass verges all over Wythenshawe, return the 49 workers to Wythenshawe Park, use the £Millions we get from the Airport to create Jobs in Wythenshawe, the more money the Airport makes, the more it donates to employment of people in Wythenshawe. The Airport once promised through Councillors to reduce the rates of people in Manchester, look at the poor areas that have high unemployment & give them jobs. The Airport is expanding all the time & it is the Rate Payers of Manchester who have paid for it over many many years, it belongs to the people of Manchester, listen to what they have to say & stop making snide deals behind people’s backs, Councillors are paid many thousands of pounds to keep people in the dark because they are scared of the comeback. Councillors, MP’s & the Airport ow the people of Wythenshawe & Manchester big time.

The Mystery Bridge across the Mill Brook in Baguley.

I was born in September 1946 and lived in Overdale Road Benchill before moving to Fouracers Road in Baguley about 1951. The Lanes, Farms and Fields of this time had only recently disappeared from this Cheshire landscape and surrendered to the spreading Wythenshawe Estate. Fouracres Road was on the edge of this invasion recently covered by a type of house known as Riley or Boots and known locally by the kids as “Tin Town” Exploring these lanes started almost from our front door and summer strolls up Clay Lane, Floats Road, Dobinetts lane led to Ringway Airport or Castle Mills, or by an alternative route past Shentons Farm and down Whitecarr Lane.

Surrounded by my “Tin Town” were remnants of an earlier age in the form of a solidly built house called Fouracres, occupied by a Doctor. But my curiosity focused on remnants of a cobbled lane cut short and built over by Fouracres Road at the present day junction ot of Holyhedge Road, Southmoor Road and the new Metro tram route. This lane which I later discovered was called Dunns Lane and ran by the Mill Brook from its start at Floats Road. As a child I used this route to collect groceries from Dillys, better known to me as The Shanty being the only shop in the vicinity open on a Sunday. For a few years each summer, a number of Romany Gypsies camped on what remained of Dunns Lane as they had probably done when the lane continued to the Smithy and its junction with Green Brow Lane. (Now, the site of the Red Rose Pub). Green Brow Lane disappeared to be replaced by Green Brow Road and there was no trace of the former lane remaining……..or was there?

My first school was Baguley Hall Primary whilst awaiting the opening of St Peters on Firbank Road and later progressed to St Pauls. Until 1962. At that time there was still remnants of Truck Lane on its winding way to Haverley Hey. My route home was along Cowlishawe Road past Newall Green School and there were frequent threats of being “ambushed” thankfully that never happened.

By the time I was 13 I was delivering newspapers from Taggarts and earning a few extra coppers on a Saturday night selling the Empire collected from the Royal Oak. As a favour for a friend who was away on holiday, I took over his newspaper round from Dillys, The Shanty and delivered papers to a few old houses at the start of Dunns Lane. These houses were interesting in that they could only be accessed across individual wooden foot bridges across the Mill Brook. I then had to retrace my steps along Floats Road for the rest of the round. None of the houses served were numbered and I had to remember the sequence of occupier’s names. 60 years later I still remember having to chant some of the names where deliveries were made. Dougall, Redcott, Andrews, Flemming followed by Belling, Shawe, Robertson, Prince finishing up with Rimmer on Dobbinets Lane. Some of there older cottages fronting FairyWell Wood still had outside water pumps.

By the time I was 14 I joined the Air Training Corps in Hulme and in quick succession started work with A.V.Roe (British Aero Space) at Woodford Aerodrome. At the time my only transport was by bicycle and the harsh winter of 1962 put pay to that as I was also burning the candle at both ends as Drummer with Paul Fenda and the Teen Beats following a cabaret circuit covering a wide area beyond Wythenshawe.

Cutting a long story short by 1970 my job took me North and have since lived in a small town just off the Yorkshire Coast and almost on the North Yorkshire Moors where after retirement I took up a new part time on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway.

To return to Wythenshawe I made infrequent visits to a declining number of family and friends which brings me back to my earlier memories of Baguley and the Mill Brook. The memories of which I researched from afar.

As a boy of about seven I explored the Baguley Mill Brook from a bridge over Clay Lane and immediately entered a long concrete culvert which I crawled through emerging in an area of green field and trees between the new Greenbrow Road, Morvern Drrive and Amberley Drive Flats. In my memory this area was never built on and I knew of a small brick bridge over the Mill Brook which has puzzled me ever since. Where did the bridge come from and where did the long lost paths lead to?

Research led me to investigate maps from the 1850 up to date and although the ancient Green Brow lane took a right angled turn near the bridge no map ever showed it to be part of the original GreenBrow Lane..

And so 60 years on I have decided to make an appeal to Historians and Archaeologists to help finally put my mind to rest about the story of this very insignificant piece of Wythenshawe history still locked in my memory.

Chris Bowden April 2020.

Pingback: Wythenshawe Civic Centre

Pingback: The Charlestown Estate – Friends of Bailey's Wood

The M56 begins at the Junction of Altrincham Road (A560) and always has. No part of Princess Parkway is the M56, although it has been reconfigured and now continues into the M56 but until the A560 it remains P.P.