Tags

In 1971, the Hulme Crescents were thought to represent the best of modern social housing as we saw in last week’s post. The planning principles which inspired them were intended not only to provide decent housing but to honour and foster community. The construction techniques which built them had seemed to promise mass housing on a scale and at a pace which would finally eradicate the scourge of the slums.

If only briefly, this excitement was felt by residents as well as politicians and planners: (1)

I went for a walk with my granddad before the Crescents started to get bad. And they were wonderful places. Full of really new ideas and loads of hope for the people living in them. People talked to each other. And I can remember laugher with a family that lived in them. They asked me and my granddad in for a cup of tea. Showed us round the strange way the flats were designed. But the flat was so clean and nice and they were so proud of it. Then suddenly, about 1972 I think it was, things started to go wrong.

What did go wrong?

First and foremost, the Crescents’ system-built engineering was a disaster. The blocks were erected too quickly and their construction inadequately supervised. Reinforcing bolts and ties were missing; problems of condensation emerged from poor insulation and ventilation; vermin spread rapidly through the estate’s ducting. (2)

Whose fault was that? Local authorities – pressured by central government and driven by their own ambitions to build big and build fast – can certainly take some blame. The Government’s National Building Agency, which promoted industrialised building but failed to provide any effective oversight, is also responsible.

But arguably it is the cartel of construction companies which dominated system-built housing in the sixties and early seventies which is most culpable. The construction industry sold products unfit for purpose and failed to meet even their own standards of quality control. (3)

The collapse of Ronan Point in May 1968 was an early indicator of this looming disaster and had its own impact on the Crescents. Plans for gas-fired central heating were jettisoned in favour of a system of underfloor heating. After the 1973 oil crisis, when fuel prices rose six-fold, this became prohibitively expensive for the estate’s new residents.

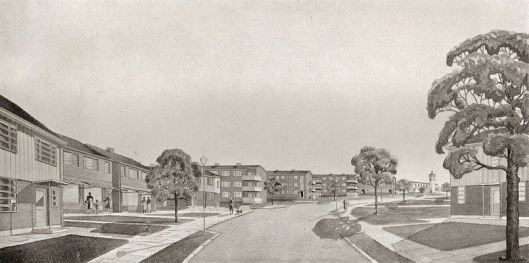

View between Robert Adam Crescent and William Kent Crescent (to left) 1976 © Visual Resources at MMU

There were also foreseeable design flaws. The dense street layout which had previously connected Hulme to itself and the city was abandoned; the busy main thoroughfare, Stretford Road, closed. Two large highways, the Mancunian Way and the Princess Parkway, enclosed and isolated the estate. The open space between the Crescents – intended as an amenity – was largely just that and lacked form and function. It came to feel rather desolate. (4)

In 1974 a five-year old child died after falling from a top-floor balcony and matters came to a head. 643 residents signed a petition asking to be moved. A 1975 survey revealed that an overwhelming 96 per cent of Crescent-dwellers wanted to leave the estate. The Council agreed no family should be required to live above the ground floor in any of its deck-access homes.

In 1974 a five-year old child died after falling from a top-floor balcony and matters came to a head. 643 residents signed a petition asking to be moved. A 1975 survey revealed that an overwhelming 96 per cent of Crescent-dwellers wanted to leave the estate. The Council agreed no family should be required to live above the ground floor in any of its deck-access homes.

At the same time, vandalism and crime were rife – a litany, familiar from the other council estate badlands of the day, of muggings and break-ins, graffiti and destruction, compounded by the Housing Department’s failure to adequately maintain and supervise the estate.

There’s no denying that in the case of the Hulme Crescents there were inherent design flaws which contributed to social breakdown on the estate. But there is also a bigger picture which is often neglected in their story.

The majority of former Hulme residents had, in fact, been rehoused in out-of-town estates. Given its early problems and deteriorating reputation, the Crescents rapidly became hard-to-let. As was typical in such circumstances, ‘problem families’ and vulnerable tenants – who had little choice in where they might be housed – came disproportionately to be settled there.

A 1973 survey showed the estate to be the most deprived in Manchester. The 1978 World in Action report – a searing exposé of what it described as ‘a British Bantustan’ – estimated 60 per cent of residents were in receipt of benefit. (5)

This was a reality that would have challenged any form of housing – as we’ve seen where similar circumstances affected suburban estates such as Blackbird Leys in Oxford or Norris Green in Liverpool. But the Hulme Crescents offered a perfect storm of disadvantage. They were ripe for political action.

Campaigning groups – a mix of housing activists and local residents – began to spring up. Manchester and Salford Housing Action was established in 1973. The Hulme Tenants’ Association and Hulme People’s Rights Group were active by the mid-seventies, the latter provided offices on the estate by the City Council who came to regret the opportunity offered to their political opponents. These groups skilfully made use of a media far less deferential than it had been – in reporting city planners’ visions – in the 1960s.(6)

The Council still hoped something might be salvaged from the Crescents. In 1978, it proposed housing single people and students in the estate and suggested the blocks be subdivided.

The latter never occurred but the removal of families was achieved by 1980. An anarchic free-for-all developed that created ‘Planet Hulme’. This was ‘a Modernist utopia decaying, gone crumbled and decadent’; a creative, Bohemian enclave. But it, despite Owen Hatherley’s celebration of its vibrant subculture, went bad too and became – at least to the few ‘ordinary’ residents that remained and certainly to more conventional citizens – a frightening place: anarchic in the most pejorative sense of the term. (7)

The case for the Crescents’ demolition came to be seen as overwhelming as political attitudes shifted too. A Labour left emerged, critical of what it regarded as the paternalism of traditional Labour local government and committed – it claimed – to promoting genuine participation. This new left controlled the City Council by the early eighties.

For Peter Shapely, a rising ideology of consumerism which transcended party politics – and certainly underlay it – was more important. At any rate, the design and planning process which would build the new Hulme was a very different animal to that which operated in the sixties.

In 1988 it looked as if Hulme would form the testing-ground for the Thatcher government’s Housing Action Trusts. Tenant resistance to this bureaucratic and top-down initiative blocked the attempt to impose a Trust on Hulme and established the principle of a tenant ballot in future HAT proposals.

The outcome for the Crescents was the Hulme Study – a generously-funded joint initiative of government, council and residents to study the estate’s future. It didn’t produce much more than a report but a marker of participation had been set down.

This wasn’t immediately obvious in what became the transforming moment of the estate – the City Council-led bid for City Challenge funding in 1992. But the essence of the new approach was the buzz-word ‘partnership’ and a complex nexus of central and local government, private investors, construction companies, housing associations and tenants came together to form the new Hulme.

Hulme Regeneration Ltd took the lead – a joint company comprising the Council’s Hulme Subcommittee and development company AMEC. The subcommittee itself included Hulme Community Homes – another three-way partnership of housing department, housing associations and tenants. And then there was the Hulme Tenant Participation Project – an autonomous body funded by City Challenge and Housing Corporation.

This was all as complex and strife-ridden as it sounds but the tenants did in the end wield significant influence and in key respects came – alongside some new planning wisdom and in opposition to other – to determine the key elements of the new estate. (8)

As to that, you can take the short version or the long. Tony Hughes, a caretaker for the North British Housing Group – which was one of the key players in the new Hulme –states simply, ‘We wanted more houses than flats, gardens, lots of greenery and safe areas for children’ (9)

The long version is contained in the 40 page Guide to Development in Hulme published by Hulme Regeneration Ltd in 1994. (10) It’s an essential primer to what has been called New Urbanism – the attempt to ‘create a new neighbourhood with the “feel” of a more traditional urban community’.

To summarise some key aspects, the guidelines stressed permeability – busy streets which encouraged through movement. This was a principle which challenged both some of the negative characteristics of the former estate – for one, the very sense of an ‘estate’ isolated from the wider city – as well as some favourite tropes of twentieth century town planners, notably the cul-de-sac.

It sought to tackle head-on some of the most problematic elements of the Crescents as they had evolved – the no-go zones and ‘escape routes’ which encouraged crime and vandalism – and replace them with the ‘natural surveillance’ of streets:

Streets will once again provide both a means of communication and transport, and – together with well-defined squares and civic spaces – a self-supervised area of public contact and interaction.

Much more could be said of the key themes outlined – the call for ‘landmarks, vistas and focal points’ and the demand for ‘a clear definition of public and private space’ most notably – but the measure lies in the new Hulme that actually emerged.

The Crescents were finally demolished in 1994, replaced – for the most part – by a pretty conventional streetscape of red-brick terraces (‘Barratt rabbit hutches’ in Hatherley’s words) and functional low-rise flats. The architectural exception is the small Homes for Change development – a product of the ‘alternative Hulme’ of the eighties which chose to build a little oasis of deck-access Brutalism.

The goal of mixed tenure has been achieved. In 2002 there was a mix of 42 per cent public sector housing, 22 per cent housing association and 36 per cent private. Now, as Manchester City Council has comprehensively embraced the world of ALMOs and not-for-profit housing providers and divested itself of direct responsibility for housing, the proportion of housing association properties is much higher. (11)

Tellingly, the 2006 evaluation of Hulme’s regeneration notes that the ‘quality of private housing and its maintenance has been problematical, while the quality of public sector and housing association dwellings appears to have been much higher’.

Housing type doesn’t magically transform social and economic realities. The same report described relatively high levels of crime – though falling – and unemployment levels of 17 per cent – five or six times above the national average though still a significant fall from the 30 per cent previously reported. Still, those wishing to move from Hulme had fallen by 63 per cent and the redevelopment as a whole was a success.

It’s been a lengthy analysis but it’s hard – in a balanced way – to summarise the Hulme story briefly. This was – there can be no doubt – a social housing disaster. Design flaws met structural failings and were compounded by a downward spiral of social breakdown.

There were high ideals and positive principles expressed in the creation of the Crescents. Incompetence – some of it wilful in terms of the actual construction – undercut any good these might have done.

The considered conclusions of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation have merit – and certainly the benefit of hindsight: (12)

Re-development in Hulme during the 1960s was imposed as the product of political ideology and architectural fashion and local people were not involved in the assessment of needs. Positive features contributing to social cohesion, continuity and a sense of identity were lost.

But then Municipal Dreams have never been shaped in a vacuum and have always been constrained by the social and economic circumstances of the day and the limitations – rather than the malevolence – of the political actors which brought them into being.

Sources

(1) From the Guestbook of the eXHuLME Website – a great resource on the history of old Hulme and the Hulme estate.

(2) John J. Parkinson-Bailey, Manchester: An Architectural History, 2000

(3) This is described in Adam Curtis’ 1984 BBC documentary ‘Inquiry: The Great British Housing Disaster’

(4) Ted Kitchen, People, Politics, Policies and Plans: The City Planning Process in Contemporary Britain (1997)

(5) World in Action, ‘There’s No Place Like Hulme’, 10 April, 1978

(6) Peter Shapely, ‘Tenants Arise! Consumerism, Tenants and the Challenge to Council Authority in Manchester, 1968-92’, Social History, Vol. 31, No. 1, February, 2006

(7) Owen Hatherley, A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain (2010)

(8) All this is best outlined and in greater detail by Alison Ravetz, Council Housing and Culture: The History of a Social Experiment (2001)

(9) Quoted in Laurette Ziemer, ‘Social Climbing: Estates are Transformed’, Daily Mirror, 23 June 2001

(10) Hulme Regeneration Limited, Rebuilding the City. A Guide to Development in Hulme, June 1994

(11) Lesley Mackay, Evaluation of the Regeneration of Hulme, Manchester, VivaCity 2020, February 2006 and Tony Gilmour, ‘Revolution? Transforming Social Housing in the Manchester City Region’, ENHR 2009 Prague Conference ‘Changing Housing Markets: Integration and Segmentation’

(12) Joseph Rowntree Foundation, ‘Lessons from Hulme’, September 1994

Images, where credited, are taken from the Flikr set on Hulme’s redevelopment posted by Manchester Metropolitan University’s Visual Resources Centre.