Chris Matthews, Homes and Places: A History of Nottingham’s Council Houses (Nottingham City Homes, 2015)

It’s a pleasure to see this fine account of Nottingham’s council housing history. It’s a story well worth telling and one – in Nottingham and elsewhere – that this blog has sought to share. Above all, it is a people’s history, a history of homes and communities but it encompasses high (and low) politics too, architecture and planning and much, much else: a history of concern to anyone interested in the fabric – in the broadest sense – of our society.

If all that reads like a shameless plug for this blog, it is also a very definite recommendation for Chris Matthews’ new book. It’s a warts and all history, recording the highs and lows of Nottingham’s council housing and Nottingham City Homes is to be congratulated for commissioning a serious and well-researched account. There’s a place – a very proper place at a time when social housing’s past is traduced and its future near written off – for a more straightforwardly celebratory history but this is a book which anyone interested in a nuanced understanding of our housing history should read.

Chris Matthews provides a thorough chronological account which I won’t attempt to replicate in this brief review – the illustrations alone (over 120 carefully selected and well reproduced black and white and colour images) tell a compelling story. But I will pull out a few of the themes which struck me in my reading of it.

Victoria Dwellings, now the Victoria Park View Flats under private ownership

We’ll begin with the need for – the absolute necessity of – council housing. In this, Nottingham was a comparatively slow starter despite a problem of slum housing which was – as a result of the Corporation’s failure to expand into the open land enclosing the city’s historic core – amongst the worst in the country. Early efforts, notably the Victoria Buildings on Bath Street completed in 1876 (and second only to Liverpool), were not followed through and it was the large peripheral cottage suburbs built in the 1930s which constituted the city’s first serious attempt to rehouse its slum dwellers.

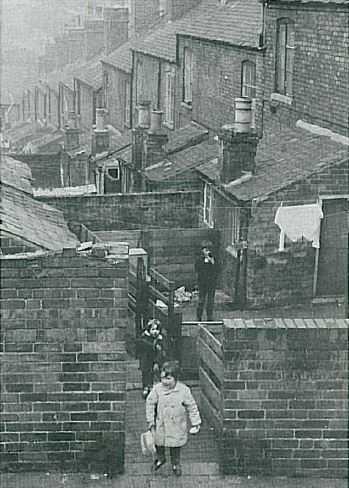

Narrow Marsh, 1919

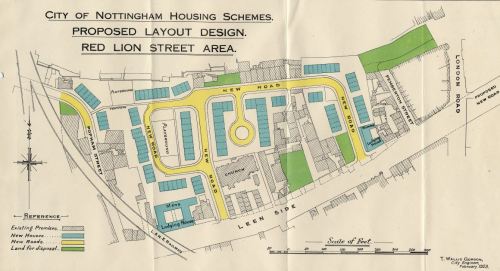

Council plans for the redevelopment of the Red Lion Street area of Narrow March, 1920s (with thanks to Dan Lucas)

What is more easily forgotten is the persistence of unfit housing. As late as 1951, 43 per cent of Nottingham homes lacked a bathroom. Into the 1960s, in the long neglected St Ann’s area most houses lacked an inside toilet and bath; 53 per cent had no proper hot water supply. All this provides a context for the mass housing programmes of this later period which we are quick to condemn – for their undoubted deficiencies – but so little understand.

St Ann’s, an image taken from the City Council’s 1970 redevelopment brochure ‘St Ann’s: Renewal in Progress’ (with thanks to Dan Lucas)

New housing in St Ann’s © John Sutton and made available through a Creative Commons licence

It follows, therefore, that these new homes were embraced by their residents: ‘the sheer luxury of four bedroomed houses with an inside flush toilet…a really big bath’ as a tenant of the interwar Broxtowe estate recalls. But even high-rise dwellings, later condemned (literally so and demolished in many cases), were welcomed. One new tenant of the maligned Hyson Green flats describes ‘an indoor bathroom, beautiful kitchen. It was paradise, absolutely paradise’. Marcia Watson, a young black woman (now a city councillor) remembers:

High rise was popular then. People weren’t fussy back then. The view was beautiful. Absolutely beautiful. I loved it…for me, moving in and living there, it was the first home of my own.

Council homes were important for providing a disadvantaged minority community with their first decent homes and a step up, as they did for so many others. Matthews argues, rightly, that council housing provided the ‘biggest collective leap in living standards in British history’.

It was good to see this quoted – and hopefully sincerely endorsed – by prime minister Theresa May no less in her keynote speech on social housing made to the National Housing Federation in September 2018. The speech was taken to herald a sea change in contemporary Conservative attitudes towards both the past value and present necessity of social housing. We’ll wait and see.

This looks like a 1950s development but the privet hedges and greenery are in keeping with Howitt’s ideals © SK53 and made available through a Creative Commons licence

We might take those sanitary essentials celebrated by Marcia Watson for granted now (though too many can’t) but the quality of much council housing is striking too, how much could be done ‘by the steady and consistent exercise of careful thought and skilled imagination’. That was Raymond Unwin, no less, praising Nottingham’s interwar council housing, recognised – thanks to the visionary leadership of City Architect TC Howitt – as some of the best in the country.

In fact, most Nottingham council homes – even in the 1960s – were solid, well-built terraced and semi-detached two-storey houses which, though sometimes lacking the aesthetic of Howitt’s work, continued to provide decent family homes for many who could not afford or did not wish to buy. It’s an irony that some of the very best council housing up and down the country was built in the 1970s when, with lessons learnt from recent mistakes, low- and medium-rise, predominantly brick-built estates were erected. Nottingham built more council housing in the 1970s than in any previous decade.

Osier Road, the Meadows

The Meadows scheme was built with such intent, its Radburn-style cul-de-sacs and greens incorporating the planning ideals of the day by their separation of cars and people. Those ideals are now held to have ‘failed’ and there are proposals to restore a more traditional streetscape to the estate. You can take this as an emblem of planning hubris or, more properly in my view, as a reminder of how transitory the ‘common sense’ of one age can seem to another. Posterity should perhaps be a little more humble and not quite so condescending.

This brings us, inescapably, to the politics of council housing. There has in the past been – these seem now like halcyon days – a broad consensus on the topic. William Crane, a Conservative and building trades businessman, was chair of the Housing Committee from 1919 to 1957, surviving several changes of administration and building over 17,000 council homes in the interwar period when Nottingham was among the most prolific builders of council housing in the country.

Edenhall Gardens, Clifton Estate © Alan Murray-Rust and made available through a Creative Commons licence

Then there is the politics of the post-war period when Labour and Conservative governments vied to build the most houses with council housing as a central element of the mix. The Clifton Estate, a scheme of over 6000 homes housing 30,000 built to the south of the city between 1951 and 1958, encapsulates some of these ideals, not least in its focus on neighbourhood. Planning ideals are not always fulfilled, particularly in local authority building where they nearly always conflict with budgetary constraints, but still the Estate’s early isolation, expense and lack of facilities probably didn’t merit its description (in a 1958 ITV documentary) as ‘Hell on Earth’ and certainly didn’t do so in the longer term.

The house-building ‘arms race’ came to a head in the 1960s when high-rise and system building were seen as the modern means to build on a mass scale and rid the country, once and for all, of the scourge of its slums.

The refurbished Woodlands group of high-rise blocks in Radford © John Sutton and made available through a Creative Commons licence

Here Nottingham provides some salutary lessons. The city embraced these methods, these ambitions and, yes, these ideals. High-rise and deck access developments were adopted; major contractors, notably Wimpey and Taylor Woodrow, employed to build their off-the-peg schemes across the city. Matthews is candid in acknowledging the defects of these estates whilst rightly noting the legislative and economic changes which were also afflicting disproportionately the communities which lived in council homes. Equally honestly, he addresses the dissatisfaction with the council as landlord in this period, particularly in relation to repairs. The combination was stigmatising – ‘no longer was renting a council house aspirational’.

A part of the Hyson Green scheme prior to demolition

Beginning with the deck-access Balloon Woods Estate (a Yorkshire Development Scheme completed in 1969) in 1984, with point blocks at Basford and deck-access at Hyson Green following shortly after, many of the troubled developments of the later 60s and early 70s have been demolished. Low-rise traditional housing has mostly taken its place. Others have been thoroughly refurbished through Estate Action programmes and suchlike. One hundred per cent of current stock now meets Decent Homes standards.

Tony Crosland as Sec of State opening Nottingham’s 50,000th council house in The Meadows with Chair of Housing, Cllr Bert Littlewood, 1976 (with thanks to Dan Lucas)

By 1981, almost half of Nottingham’s people lived in council homes; some 50,000 had been built in preceding years. But the bomb had dropped. In fact, a Conservative-led administration in Nottingham had sold off 1635 homes to existing tenants by 1977 (for more detail on this, do read the comment by Dan Lucas below) but the Right to Buy enacted by Mrs Thatcher’s government in 1981 would see 20,761 homes lost to the Council in the next quarter-century. The Labour chair of the Housing Committee in the 1990s describes its role as simply ‘trying to hold the fort’. There was as the title to chapter 6 declares a ‘Right to Buy but no Right to Build’.

Nevertheless, a lot – in terms of the demolitions and rebuilding noted above – was achieved. The Decent Homes programme was a positive ‘Blairite’ achievement though marked by an unwonted antipathy towards local government. The latter led – a necessity if central funding for improvements was to be secured – to the creation of a new arm’s-length management organisation in 2005.

An impression of some of the new council housing to be built, in Radford

Nottingham City Homes would be one of the largest ALMOs in the country, managing 28,000 homes. After a troubled start, it seems justifiably proud of its recent achievements, not least a building programme of 400 new homes to be completed by 2017. Indeed, as Matthews argues, the commissioning of this history itself marks a ‘renewed confidence in Nottingham’s council housing’.

It’s desperately sad that this – in broader terms – is not a confidence shared by the current government, driven by an ideological hatred of social housing and a fantasy of owner occupation for all – though even that, perhaps, is to give it too much credit. The reality is that this government is willing to consign our less affluent citizens to an increasingly marginalised and diminished social housing sector and the tender mercies of private landlordism.

That makes this honest, intelligent and informative account of Nottingham’s council housing all the more important. As Chris Matthews concludes:

The history shows that, alongside other tenures, council housing can and does transform lives, providing a solution to a wide range of housing problems.

Buy the book, spread that message.

Notes

This webpage provides full details on how and where to purchase the book.

My thanks to Dan Lucas, Strategy and Research Manager for Nottingham City Homes and a key contributor to the book, for providing some of the images used in this post.

Alex Ball, a Labour Councillor for Nottingham City Council with responsibilities for Housing and Regeneration in the city, contributed an earlier guest post to the blog: Nottingham’s Early Council Housing: ‘Nothing like this had been seen before in the city’

In recent years Chris Matthews has worked with a Nottingham group called TravelRight to write and design guides to the city’s north west suburbs, particularly council housing estates in Aspley, Bilborough, Broxtowe and Strelley. Some of these guides are worth attention too (I can send you copies). Taken together, plus other council estates in Bulwell, Lenton Abbey and Whitemoor, and what you have is, probably, the largest garden city in England. It is one of Nottingham’s unsung treasures and Chris working with TravelRight has done more to remind us of its existence than anyone else. Chris and Dan have produced a first-rate history I would recommend to everyone (before I retired in 2006, I was news and reviews editor of ‘Local Hisory Magazine’ for twenty-two years and know a good local history when I read one).

Thanks for your comment and it’s great to hear of Chris’s other writings. I wish work of this kind was produced more widely – it’s a neglected topic in so many local histories. But obviously Nottingham is worthy of special attention and I’d love to read more!

For an example of Chris’s excellent guides go to: http://nottingham.travelright.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Aspley-Local-History-booklet.pdf

There are others available on the same website.

Many thanks for such a positive review.

I would just like to make one small point of clarification about a rather interesting episode related to this point:

“In fact, a Conservative-led administration in Nottingham had sold off 1635 homes to existing tenants by 1977”

This is not 100% correct, and I believe the following is of some note. I understand the administration concerned sold to tenants and held empties which they made available to sell to anyone who was on the ‘waiting list’ – since the waiting list was essentially open this was a route into cheap home ownership for those who could afford to buy. At the time, with long waiting lists of those unable to afford to buy, this was seen as controversial, and to some, perhaps even a scandal.

The matter was featured in an ITV documentary in 1978 called TV Eye, made by Thames TV – which featured both Nottingham and the GLC, who were operating a similar policy in London. The documentary makers applied to purchase a house in the name of Mr Terrence Victor Eye (T.V. Eye…) to illustrate that someone with little or no connection with Nottingham (and in fact not even a real person in that instance) could gain keys to look at a house and make an offer that would be accepted, to purchase it.

Council House sales did not start with this, and sales have a longer history – including in Nottingham, but in retrospect this was a precursor to Right to Buy (RTB), given the vigour which the policy was pursued. Thus an important part of this history.

Whatever the pros and cons of RTB are there is no doubt that it is one of the most significant policies (possibly the most significant) in council housing history, the cause of one of the biggest tenure shifts in UK housing history, and something that has been described as the biggest UK privatisation of them all, dwarfing all of the industrial privatisations of the 1980s and ‘90s put together.

Dan Lucas

Nottingham City Homes

Do you have a source for that story Dan?

Reblogged this on Art History blog and commented:

Homes and Places looks like an excellent history of Nottingham Council Housing. When I am next in Nottingham I will buy the Book and the radical bookshop looks excellent . I only wanted to say that tragically Labour controlled City councils like Nottingham , Liverpool , Manchester are letting their council house stock be managed by Housing associations or ALMO’s and there is very little Council House stock left . I know because I Live in Kettering and am a Tenant of Nottingham Community Housing Association which has a lot of Social Housing to Manage and the tragedy is that Cameron and Co have set out to demolish ,destroy what is left of Social or Council Housing. Laurence

An interesting read. I live in Cornwall now, but grew up in Nottingham and lived in council housing in Bilbrough and then Top Valley. My mum went on to buy a council house cheaply just off from the City hospital, which I always had mixed feelings about, as she was living in a 3 bedroomed house on her own. She has now sold it and got a bungelow but that house will never be available to those who can’t afford to pay private rents.

I remember well the flats at Hyson Green and Radford, having lived in a bed sit there when I first left home and also the big green gardens of Bilbrough. I’m a historian and it is good to see this subject being written about. I will buy the book!

So many memories. Dreadful housing in Radford in 50’s; then excellent housing in Broxtowe, Strelley, Aspley. Need to read this book!

It was good to hear the Prime Minister Theresa May quoting from this book in her speech to the National Housing Federation in September 2018!

From page 9 of the book’s introduction:

Mrs May said: “The rise of social housing in this country provided what has been called the “biggest collective leap in living standards in British history”.

“It brought about the end of the slums and tenements, a recognition that all of us, whoever we are and whatever our circumstances, deserve a decent place to call our own.”

https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-to-the-national-housing-federation-summit-19-september-2018

Pingback: A new message from a Conservative prime minister | Jules Birch

Pingback: Council Housing in Winchester – Part II post-1945: ‘Visually pleasing and economic in development’ | Municipal Dreams