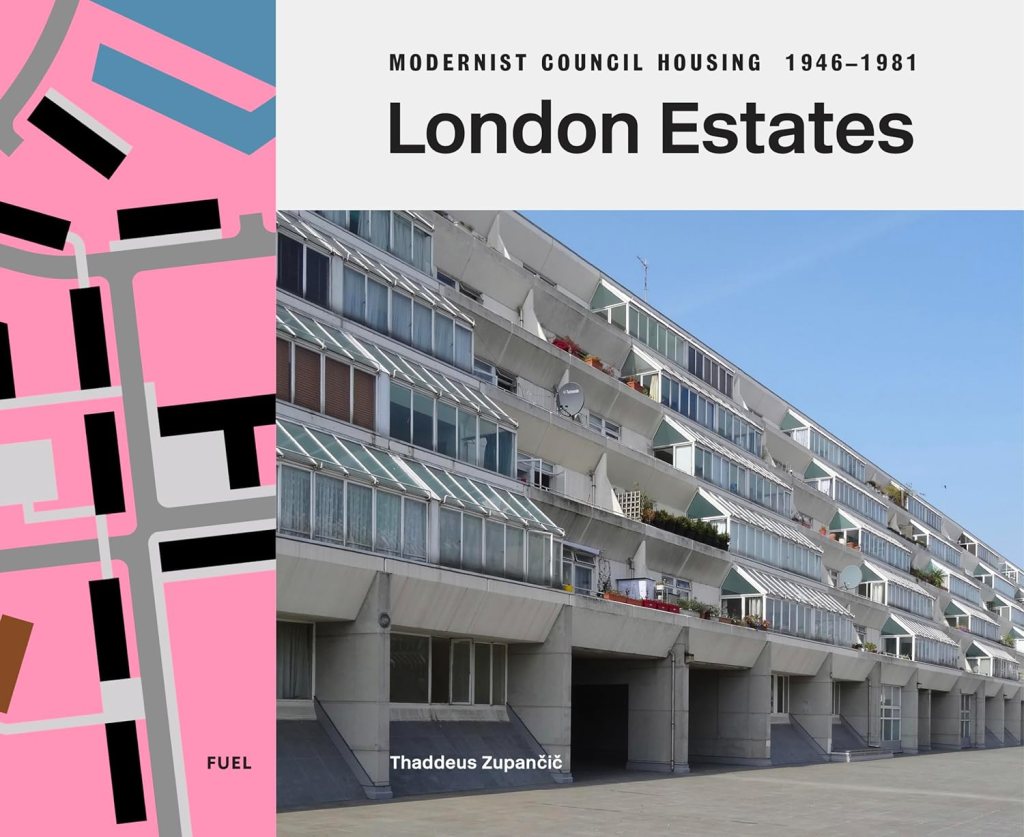

Thaddeus Zupančič, London Estates: Modernist Council Housing 1946-1981, (Fuel Publishing, March 2024)

Council housing, often hidden in plain sight, is arguably the greatest gift that architects have bequeathed London. Just as importantly, it has contributed immeasurably to not only the architectural, but also the social fabric of the capital.

You won’t be surprised to learn that I’m happy to endorse these words from Thaddeus Zupančič in his introduction to London Estates and I’m delighted that his new book provides such a superb photographic record of that contribution in the post-war years.

The photographs are, of course, the main course and you’ll see a representative sample on this page with supporting data from the book. But I’ll begin by commending the introduction – a succinct but detailed summary of the institutions, individuals and ideas that shaped council housing in the capital after 1945. Its breadth and precision are a testament to the expertise and zeal Thaddeus brings to this project as are the captions to the photographs listing the schemes’ architects and dates. It can be easy to glide over the latter but they’re the fruit of a lot of hard work and research where some detail can be surprisingly confused or murky.

The photographs themselves are excellent – capturing the essence and sometimes the surprising detail of the 275 estates featured in a way that avoids the sterility of more self-conscious architectural photography. As someone who photographs council housing rather amateurishly, I know how tricky this is but, while Thaddeus observes the necessary conventions that keep people and traffic out of the picture, every photo seems a crystal clear evocation of its subject. Here the estates seem real, lived in, albeit with some of the rougher edges removed. Credit here too to FUEL, the publishers, for reproducing his colour photography in a restrained, realist palette.

The book is organised into four sections providing a geographical quadrant of the capital (North-East, North-West and so on). Within these, you’ll find estates and blocks from every London borough and the City. An index provides ready access to the individual schemes. Within those geographical segments, the illustrations follow a broadly chronological order that allows you to trace the architectural evolution of London’s council housing – from the interwar legacy designs of the early post-war period to the more daring modernism and off-the-peg high-rise of the later 1950s and 1960s, to the lower-rise modesty of the 1970s.

Some of the photographs depict the ‘iconic’ estates many of you will be familiar with but many cover lesser known schemes, some rather special, others architecturally quite ordinary – the full gamut: two-storey housing, slab blocks, point blocks, terraces, ziggurats, flats, maisonettes; all of them, above all, homes.

London Estates reminds us – contrary to the lazy stereotypes and easy generalisations of some commentators – of the range and variety of council homes in the capital and the thought and ingenuity that went into providing Londoners decent, secure and affordable homes. I don’t need to draw the contrast with the present.

Currently, despite a recent, small uptick in social housing construction, we are still – as a result of Right to Buy – suffering a net loss of social rent homes. The book includes some schemes (such as the Greater London Council’s Aintree Estate in Fulham and parts of Thamesmead) already demolished and others – Grange Farm built by the Borough of Harrow in 1969, to take one example – scheduled for demolition.

You’ll have your favourites – Churchill Gardens, Cranbrook Estate, Dawson’s Heights are among mine – but you’ll be introduced to quite unexpected schemes such as Queen Adelaide Court, designed by Edward Armstrong for Penge Urban District Council in 1951 when it won a Festival of Britain award. It’s invidious to select; you can explore for yourself and, if you’re local, maybe visit a few in person.

I won’t indulge the reviewer’s habit of lamenting what the author has omitted. In 1981, there were 769,996 council homes in London, housing 31 percent of households in Greater London and 43 percent in inner London. I’m afraid – spoiler alert – not all of these are included in London Estates. But that, surely, is only an excuse for Thaddeus (who goes by the ironic monicker @notreallyobsessive on his popular Instagram account) and his publishers to produce a second volume in due course.

In the meantime, I’m very happy to recommend this book to anyone with an interest in council housing, its architecture and its evolution.

Thaddeus Zupančič is a Slovenian-born writer and translator who has lived in London since 1991. For the first 14 years, he worked as a radio producer with the BBC World Service. You might also be interested in reading Thaddeus’ post on London’s Modernist Maisonettes: ‘Going Upstairs to Bed’ published on this blog in March 2021.

Not sure if Dads estate is included in this new book but I’m going to try to look at it somehow. C

Charlotte Creed

Sounds interesting, but I’d like to know which estates are covered before purchasing. Can’t find the Table of Contents on the Internet unfortunately. Don’t live in the UK, so not much chance of me finding a copy in a bookshop to browse through.

Is Knebworth House one of them Or was it built pre war?

It’s post-war, I think, but not among the Walthamstow estates featured.

My Mother & Stepfather moved to a council flat in Maudsley House, Brentford when the six blocks on the old waterworks site in Green Dragon Lane were completed in about 1970. As I was posted to RAF Hendon early in 1971, I elected to live at home, & so until July 1974 I lived on the 20th floor of our tower. When new, the flats were very good, with four to a floor. neighbours looked after the communal space, & seemed, in the main, to get on well together. On our floor, there was a room that contained the rubbish-chute, & a room intended for some sort of communal use. This tended to be used as a store for oddments such as TV cartons, which was fine until a deranged youth tried to set fire to the flats by putting a match to the cartons. Fortunately he was defeated by the design of the building, because the concrete walls were almost impervious to catching fire, & the fact that there was a close-fitting fire-door & limited oxygen helped extinguish the fire, which resulted in a certain amount of smoke-damage. One drawback with the dense concrete walls was that they couldn’t be drilled to hang pictures, etc. Some internal walls were not load-bearing, so that’s where the pictures went.

The lobby downstairs had doors, but when built, no code system for entry. That was changed in later years to keep dossers & anyone looking for a handy toilet out. The handy toilet was often one of the lifts. Below the block was a parking-area, & the flats had a garage area with wire-mesh walls & an up-and-over door. The lifts served either odd- or even- floors, so you pretty much never knew who lived ten feet above or below you. There were no balconies. Our flat, like most, had two bedrooms, bathroom, toilet, kitchen & living-room, & was spacious enough. I quite liked living there, although if the lift was unserviceable you had to get the other one so far & then use the stairs. Not so bad, but – on the odd occasion when both lifts were out, a 20 floor climb certainly developed your muscles, & was an ordeal for some older people. My folks lived there for about 10 years, & I heard that after they moved out the blocks became rather more unkempt & scruffy, which is the sort of thing that happens when tenants cease to care about their surroundings, & councils wish to save money on maintenance. Tower blocks have had quite a lot of negative press, but I thought that ours were built to a high standard, & provided good accommodation 50 years ago.

Many thanks for sharing that experience and insight. It fits quite well with that I’ve heard of other tower blocks. Provided they were built well and the lifts were working, they provided decent homes – and, of course, residents needed to be protected from antisocial behaviour.