Tags

Hull, as I hope you all know, is the UK’s City of Culture for 2017. You really don’t need an excuse to visit the city but, if that’s an incentive so much the better, because it’s worth it – Hull is one of the friendliest and most interesting places I’ve been to in a long while. What follows – touching on the city’s civic planning and an eclectic mix of some of its municipal highlights (I’ll do some housing stuff in future posts) – can only be an appetiser but I hope it will encourage you to explore the city for yourself. This first post looks, in particular, at twentieth century plans to reconstruct the city.

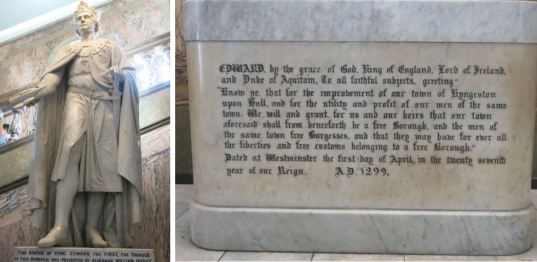

Edward I and the city’s first borough charter commemorated in the Guildhall

Hull’s been a borough since 1299 and you’ll see some very early town planning in the grid-like pattern of streets off the High Street in the Old Town. These were added to the original riverbank settlement by Edward I who wanted the prosperous port as a base for his forays against the Scots and who renamed it formally Kingston upon Hull in the process.

The port – it was the UK’s third largest into the 1950s – and its associated industries expanded massively in the centuries which followed. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Council – a reformed municipal corporation in 1835 and a county borough from 1888 – desired a civic presence which reflected the town’s importance and prosperity. In the interwar period, new ambitions emerged to improve the city, a typically squalid product of breakneck Victorian-era urbanisation, as a living and working space for its broader population. And then the Blitz – which hit Hull harder than any British city outside London – added its own necessity and aspirations to the task of post-war rebuilding.

The city centre (west-east) just before the Second World War. The newly completed Queen’s Gardens dominate the top of the image; Paragon Station is bottom centre with Jameson Street heading up. (From Lutyens and Abercrombie, Plan)

A 1943 RAF reconnaissance shot (north-south) showing city centre bomb damage (From Lutyens and Abercrombie, Plan)

Arriving by rail at Paragon Station brings you to the heart of a new Hull planned by an ambitious Corporation from the 1930s. Then, the city centre slums which dominated the area were described by Sir Reginald Blomfield, the architectural eminence brought in to oversee the scheme, as an ‘eyesore and menace to health … a disgrace to a progressive city’. He planned to replace the ‘irritating and unsightly jumble’ of older buildings with a neo-Georgian ensemble; the Council itself hoped that Ferensway, as the new thoroughfare was named, would take ‘its place among the famous streets of the world’. (1)

Brook Chambers, Ferensway

To be honest, there’s not much to vindicate such hopes now but look north to the junction with Brook Street and you’ll see a vestige of them in Brook Chambers, erected in 1934. In the event, wartime devastation – almost half the city’s central shops were destroyed – created new urgency and new opportunity to rebuild on a larger scale.

The Lutyens and Abercrombie Plan’s grand zonal reimagining of central Hull

Planning for ‘this second refounding of the great Port on the Humber’ began in 1941 and were finalised by 1944, commissioned by the Council from the two foremost town planners of the day, Sir Edwin Lutyens and Professor Patrick Abercrombie. (2) Lutyens had spent almost twenty years designing New Delhi; Abercrombie drew up influential post-war plans for London and Plymouth amongst others. Although Lutyens died in January 1944, his imprint on the completed Plan for the City and County of Kingston upon Hull seems strong in the grand Beaux Art scheme devised though it’s a form also favoured by Abercrombie in Plymouth.

More broadly, the Plan incorporated, in the words of Philip N Jones: (3)

the three great themes of post-war planning in Britain – inner city redevelopment; commitment to the social ideal of neighbourhood planning; and the trilogy of Containment – Green Belt – New Town.

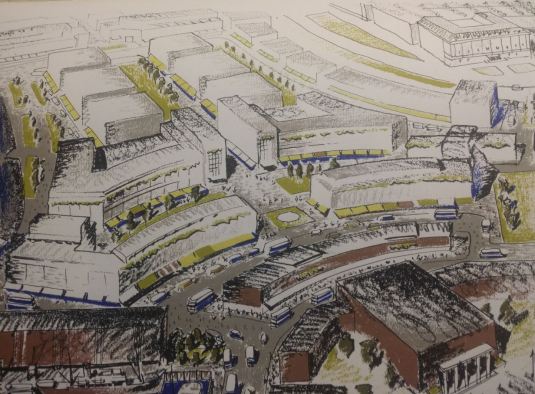

A satellite town was planned in Burton Constable eight miles to the east with a narrow Green Belt separating the new settlement from the Hull suburbs. Neither emerged and the new centre planned, in Abercrombie’s words, as ‘something completely new in Shopping Centres’ – ‘a highly specialised precinct, free from traffic but adjacent to the central traffic routes’ – also took a very different form from that originally envisaged.

The sleek new shopping centre around Osborne Street envisaged in the Lutyens and Abercrombie Plan)

Abercrombie and Lutyens had hoped to create a new shopping centre centred on Osborne Street, adjacent to an expanded and re-formed civic quarter located around Queen’s Gardens. Established business interests and the prevalence of surviving buildings – despite the Blitz – stymied this vision.

The Lutyens and Abercrombie plan shows a re-sited main railway station and new shopping centre to the south-west

The alternative Chamber of Trade plan keeps a revamped shopping centre to the north. With thanks to Catherine Flinn.

The Chamber of Trade Plan – first mooted in 1947, drawn up by another eminent town planner, WR Davidge, and adopted in modified form in 1954 – was constructed on the foundations of the main existing shopping centre to the north and was seen as far less disruptive. It incorporated ‘temporary shops’ on Ferensway which survived until 2013.

Temporary shops on Ferensway. With thanks to Catherine Flinn.

Still, something of Abercrombie’s influence remained, not least in the fact that the plan was overseen by Hull’s new planner, the grandly-named Udolphus Aylmer Coates appointed in 1948, who had been a student of Abercrombie’s at the Department of Civil Design at Liverpool University. (4)

Abercrombie himself thought that the Hull Plan was ‘probably the best report he had been connected with’ but, ironically, as Philip N Jones concludes, ‘no other wartime plan was so ignored or so apparently ineffective’. (5)

The House of Fraser store on Ferensway and Jameston Street

Nevertheless, the rebuilt streets that emerged offer an impressive testimony to the vision and design aesthetic of post-war reconstruction, most notably in the House of Fraser department store (originally Hammonds) on Ferensway and Jameson Street. Designed by TP Bennett and Sons and opened in 1950, it’s commended by the new Pevsner for its unusual combination of 1930s and Festival of Britain architectural elements. Like a number of businesses in the vicinity, it seems to have suffered from that later iteration of our commercial future, the indoor shopping centre, but the building itself remains, to my eyes, strikingly attractive.

Paragon Square towards Jameson Street

Across the road is a bit of more standard post-war neo-Georgian but, if you look very carefully to the bottom right of the image above, you’ll catch a glimpse of Tony, a local bus driver playing the spoons and giving a one-man band show before starting his shift. He wasn’t busking. As he told us, it was just a way of cheering people up and putting himself in a good frame of mind before work. He gave us a brilliant introduction to Hull and its people.

Festival House, Jameson Street

Just along Jameson Street is Festival House where a tablet marks it as ‘the first permanent building to arise from the ashes of the centre of the city’ after its wartime destruction.

If you’ve just arrived, the telephone box in the centre of Jameson Street might be the first of Hull’s famous cream-coloured kiosks you’ll see. This one looks like a Gilbert Scott’s K6 1930s’ design to me but experts can correct me. The unusual colour (and lack of crown insignia) isn’t an affectation but a proud reminder that Hull Corporation inaugurated its own municipal telephone system in 1902 which remained free of General Post Office control and privatisation until finally sold off in 1999. Hull’s telephone and internet services are now operated by Kingston Communications which controversially retains an effective local monopoly.

If you’ve just arrived, the telephone box in the centre of Jameson Street might be the first of Hull’s famous cream-coloured kiosks you’ll see. This one looks like a Gilbert Scott’s K6 1930s’ design to me but experts can correct me. The unusual colour (and lack of crown insignia) isn’t an affectation but a proud reminder that Hull Corporation inaugurated its own municipal telephone system in 1902 which remained free of General Post Office control and privatisation until finally sold off in 1999. Hull’s telephone and internet services are now operated by Kingston Communications which controversially retains an effective local monopoly.

Walking on, there’s a mix of styles and ages until you come to South Street on the right where you meet Queen’s House, a huge neo-Georgian quadrangle occupying one whole block of the city centre, designed by Kenneth Wakeford and completed in 1952.

Queen’s House, Chapel Street

The photograph, of its Chapel Street frontage above, hardly does it justice but it does capture the decline of a commercial district which Abercrombie hoped would restore Hull to its pre-war eminence as a centre serving some 500,000 people.

Alan Boyson’s Three Ships mural

By this time, you will have spotted what should be one of Hull’s most proudly iconic images – Alan Boyson’s Three Ships mural, completed in 1963 and commissioned by the Co-op to celebrate Hull’s fishing heritage. The stats are impressive enough – it’s an Italian glass mosaic of 4224 foot square slabs, each made up of 225 tiny glass cubes affixed to a 66ft x 64ft concrete screen – but what I love most is the confidence of its bravura statement of local identity. And I love that it was commissioned by the Co-op, reminding us of a time when that organisation’s consumerism with a conscience (and its ‘divi’ for its working-class members) occupied centre-stage in the drive to build a fairer and more democratic Britain.

The mural in its earlier pomp above the flagship store of the Hull and East Riding Cooperative Society

The Co-op moved on; the premises were taken over by BHS and it went bust in 2016. The building now offers a ‘redevelopment opportunity’ but, whatever happens, please support the campaign to preserve the mural by following @BhsMuralHull on Twitter and signing the petition for listing.

The City Hall, Queen Victoria and the exit from the Gents toilets

From here, a right turn down King Edward Street takes you to the heart of civic Hull into Queen Victoria Square, created in 1903 some six years after Hull was granted city status. The 1903 statue of Victoria sits imperiously above some fine public toilets, added in 1923 and retaining their original earthenware stalls, cisterns and cubicles in the Gents.

Unless you’re desperate (and male), they probably won’t be the first thing you notice. On your right, stands the Edwardian Baroque City Hall, designed by City Architect Joseph H Hirst, opened in 1910. This was designed as a public hall for concerts, meetings and civic events; on the day we visited it was hosting a graduation ceremony for the University.

Ferens Art Gallery, Queen Victoria Square

Across the Square lies the Ferens Art Gallery – a ‘simple restrained classical cube of fine ashlar’ in the words of the latest Pevsner. It was completed in 1927 following a £50,000 endowment from Thomas R Ferens, a director of Reckitt’s (one of the city’s major firms) and one-time Liberal MP for East Hull. One of several significant benefactors to the city, Ferens was honoured after his death in 1930 in the naming of Ferensway.

An artwork purchased by the Corporation, one of many.

The early support of the Council is clear too among the many fine works on show. The Gallery, free to enter, with some good temporary exhibitions while we were there, is well worth a visit.

Maritime Museum, Queen Victoria Square

The civic triumvirate is completed by the Maritime Museum facing which was originally built in 1868-71 as the headquarters of the Hull Dock Company – a rare British building by Christopher George Wray who had made his name as an architect for the British Government in Bengal.

Both the dock offices (they became a museum in 1975) and City Hall were scheduled for demolition in the Lutyens and Abercrombie Plan as part of its creation of a new civic quarter – one reason perhaps, despite Abercrobie’s recognition that a ‘clean sheet approach’ would not be welcomed, why the major part of the Plan went unfulfilled.

Next week’s post continues this tour of Hull, looking at other elements of post-war replanning as well as some of its major municipal accomplishments in the city centre and beyond. And, if you’re new to the blog, I’ve written on the North Hull council estate in an earlier post.

Sources:

(1) Blomfield is quoted in ‘Slums Cleared for New Cityscape’, BBC Legacies, UK History Local to You (ND). The latter quotation is from David and Susan Neave, Hull (Pevsner Architectural Guides, 2010). Much of the detail which follows is drawn from the same, invaluable, source.

(2) The quotation is from the Preamble to Edwin Lutyens and Patrick Abercrombie, A Plan for the City and County of Kingston upon Hull (A Brown and Sons Ltd., London and Hull, 1945)

(3) Philip N Jones, ‘“…a fairer and nobler City” – Lutyens and Abercrombie’s Plan for the City of Hull 1945’, Planning Perspectives, no 3, volume 13, 1998

(4) RTPI, Rebuilding Hull: the Abercrombie Plan and Beyond (1940s) (2014)

(5) The first quotation comes from Abercrombie himself. The second and further detail comes from Jones, ‘“…a fairer and nobler City”.

For an unusual but insightful perspective on the Abercrombie Plan for Hull, listen to this track from Christopher Rowe and Ian Clark in ‘Songs for Humberside’ (1971)

My thanks to Catherine Flinn for providing some of the images specified as well as supporting detail. Her book on post-war city centre reconstruction in Hull, Liverpool and Exeter will be published next year.

Jones the Planner offers a full and more critical perspective on Hull’s post-war planning and architecture in ‘Hull: City of Culture’ (9 February 2014) and, alongside other case studies, in the book Cities of the North (2016).

On a visit to Kingston-upon-Hull a couple of years back, I was saddened to see how the introduction of two enclosed shopping precincts had sucked so much vitality out of the city centre, both the old an new town areas.

It was also distressing to see that – outside of the centre – the private car ruled supreme, turning Spring Bank and Beverley Road into pedestrian-hostile racetracks.

On a more positive note, the area around The Avenues seemed lively and characterful, Pearson Park was being enjoyed by happy families, and the Paragon Interchange served to co-ordinate public transport as much as can be done under privatisation.

And the latter brought audiences to Hull Truck’s splendid premises.

Hull is so unfairly maligned – it’s a fantastic original city. Those lovely toilets down by the Minerva pub are a sight to behold.

The Minerva toilets are now listed, but Historic England declined to list the wonderful Co-op/BHS mural. It was still there last October – I hope it survives. The loos in the photo, beneath Queen Victoria, are also pretty good. Must be something about Hull. The provision – for the City of Culture – of drinking water fountains is all of a piece with them: the importance of good public sanitation.

Pingback: Municipal Dreams in Hull, Part I: The best laid plans… — Municipal Dreams | Old School Garden

Pingback: Municipal Dreams Goes to Hull, Part II: Civic grandeur, service and convenience | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Aylesham and the Planning of the East Kent Coalfield, Part I | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Book Review: Catherine Flinn, Rebuilding Britain’s Blitzed Cities. Hopeful Dreams, Stark Realities | Municipal Dreams