From the arts and crafts estates – council-built – to the huge garden suburbs of the interwar period, we’ve followed a dream. And that dream came to fruition in Stevenage. That is not a sneer but an elegy.

The students of planning will tell you – quite rightly – how that dream first formed in the mind of Ebenezer Howard and the garden city movement he founded. But it dwelt powerfully in the lived reality and the political aspirations of a generation of working-class politicians who thought their people deserved better than the crowded inner-city slums.

Good housing, secure and well-paid employment and a healthy environment in which to bring up children – these were the goals: not revolutionary, modest but democratic in the deepest sense. And there was a time when Stevenage – and the other post-war New Towns – seemed to be their fulfilment.

The facts are straightforward enough. Patrick Abercrombie’s 1944 Greater London Plan called for a ring of new towns built beyond the green belt to house some 380,000 people who would be decanted from an overcrowded, blighted and war-damaged city.

That vision was taken up by Attlee’s new Labour government in 1945, entrusted fittingly to Lewis Silkin, a former member of the London County Council’s Town Planning and Housing and Public Health Committees, appointed to the post of Minister of Town and Country Planning. And it was, in its own way, as central to the ideal of a Welfare State as a national health service and comprehensive social security.

Planning for Stevenage New Town began early. The old town of Stevenage, home to a population of 6000, seemed an ideal location – 30 miles north of London with excellent transport links, suitable land and a local council receptive to growth. Gordon Stephenson drafted a plan – which would be honoured in all its essentials – in the summer of 1945.

The 1946 New Towns Act provided the apparatus to build, establishing the Development Corporations which would mastermind and implement these grandiose projects. The eight members of the Stevenage Development Corporation – appointed by Silkin – comprised town planning luminaries, local authority representatives and a couple of businessmen.

It was described as ‘liberal, bold and less inclined to hold a business point of view, than some others’. (1) But it was hardly democratic and Stevenage Urban District Council remained essentially a service and subservient body until the Corporation was wound up in 1980.

On 11 November 1946 Stevenage was designated the first new town. There was no hype in Silkin’s celebratory remarks, indeed there was a proud sense of a better world being born: (2)

Stevenage in a short time will become world famous. People from all over the world will come to Stevenage to see how we, here in this country, are building for the new way of life.

Then there was a hitch. As the first letters went out to local landowners, opposition mobilised. A Stevenage Residents’ Protection Association was formed. It was not reassured as the men from the Ministry arrived and very far from mollified when Silkin himself visited.

‘It’s no good you jeering. It’s going to be done’, he stated, to a very hostile public meeting. He then left – under police escort. The protestors replaced existing town signs with the name ‘Silkingrad’, in Russian-style script lest anyone miss the point they were making.

‘It’s no good you jeering. It’s going to be done’, he stated, to a very hostile public meeting. He then left – under police escort. The protestors replaced existing town signs with the name ‘Silkingrad’, in Russian-style script lest anyone miss the point they were making.

In keeping with British tradition, however, there was no Gulag but, rather, recourse to the law. The opponents’ case was initially upheld but rejected on appeal. Finally, in July 1947, the House of Lords itself sanctioned the plans.

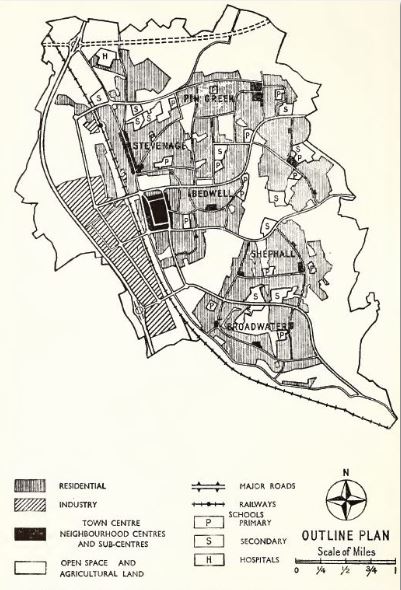

The Stevenage Master Plan which emerged, taking finished form in 1950, envisaged a town of some 60,000, dwelling in six neighbourhoods of about 10,000 each, each with their own shopping centres, primary schools and community facilities. This ideal of created community was powerful in its day. Even the street signs were colour-coded to help give each neighbourhood its own distinct identity.

A pedestrianised town centre – the first of its kind – would also be built and a substantial industrial zone would be sited, separated from residential areas, to the west of the main road and railway. Some major firms– including De Havilland (later British Aerospace), Kodak and Bowaters – would locate in Stevenage.

The first houses were begun in September 1949. By the end of 1952 1070 houses had been completed and 2367 were being built. Ten years later, 12,377 homes had been completed, all but 1177 built by the Development Corporation.

The vast majority of these were two-storey two- and three-bedroom houses, architecturally undistinguished but solid, comfortable and, of course, of much higher quality than any the vast majority of new residents had previously enjoyed. Some variety was achieved through the twelve plan variations employed.

The planners also worked hard to maintain a neighbourhood ‘feel’ with a careful range of streetscapes and designs, using curves, cul-de-sacs, ‘village greens’ and always attempting to separate people and cars. Stevenage’s extensive system of segregated cycleways was pioneering.

Interestingly, the one attempt at ‘high rise’ – a seven-storey block of 54 flats completed in 1952 in the Stoney Hall area – was deemed a failure. The Corporation – seemingly anticipating a view of high rise that would become common fifty years later – had envisaged these as middle-class dwellings but middle-class tenants were, as yet, thin on the ground. Two years later, the Corporation concluded: (3)

Almost every person coming to live in a new house at Stevenage, which is after all a country town, wants at least a small patch of garden to make the country seem yet a little closer. Discussion with representatives of the Stevenage Residents’ Federation has shown that few wish to have a flat as a home…They have expressed their desire to get away from communal staircases, balconies or landings, and to have a house with its own front door.

This brings us neatly to the sociology of the New Town. Most of the newcomers came from London but a particularly important group in the early years were construction workers. Those on London council house waiting lists prepared to work on the new town for at least six months were granted a Corporation house. Of the first 2000 houses completed, over a quarter went to building workers and their families.

They brought – and fought for – traditions of organisation and solidarity, successfully resisting victimisation, lay-offs and ‘the lump’ (labour-only subcontracting). And they provided the New Town’s residents vital early leadership – in the residents’ associations and in one-off campaigns which secured a by-pass and preserved the Fairlands Valley as open space against plans for high-density housing. Six would be elected to the local council. (4)

But they were perhaps the exception. The town planning advocates, Frederick Osborn and Arnold Whittick, welcomed the New Town’s ‘dramatic societies, art clubs, horticultural and gardening societies, political groups, sports clubs for almost every sport, numerous women’s and youth organisations’. But they acknowledged honestly that many wanted simpler pleasures and these welcomed the Locarno Ballroom opened in 1962 and the ‘American-style bowling hall’ opened the following year: (5)

The people have had well-paid regular jobs in the factories and this has conduced to producing a feeling of contentment. It has enabled them to furnish their homes well, to acquire television, cars, and domestic gadgets, so that many who came as habitual grousers were transformed into contented citizens in a few years.

This, then, was an affluent working class, enjoying domestic pleasures and rising living standards, not so much lacking class consciousness as seeming in this period not to need it. John Goldthorpe’s work on the affluent worker was published the very same year and was based on the nearby and economically similar town of Luton.

But Stevenage remained sociologically distinct, not least because the large majority of its inhabitants lived in council housing. ‘There was no sense of incongruity in Stevenage between being a young professional and living in social housing.’ (6) Social housing had not yet become residual housing for those who couldn’t afford ‘better’, still less could it possibly be considered accommodation for a so-called ‘sink population’.

And the Council and the Corporation were the benign guardians of this mixed – not classless – community, providing housing, education and leisure. At the play schemes he attended, Gary Younge recalls how, as prizes for sporting success or good behaviour, they ‘would hand out tokens for free admission to the bowling alley and the swimming pool since all were council-run’.

None of this sounds revolutionary; it doesn’t even sound like the New Jerusalem that early Labour Party activists aspired to. But it contains an essential decency and a sense of community – nothing saccharin or pious, a simple responsibility of one for the other – that superseded the ugly exploitation which been the lot of working people hitherto. We might wish for it again.

Right to buy came in the same year that the Development Corporation was abolished. And the eighties more broadly brought new – more competitive and individualistic – values that challenged the principles on which Stevenage New Town was built.

Clock tower with Franta Belsky’s 1974 memorial to Lewis Silkin. © Steve Cadnam, made available under the Creative Commons licence

Stevenage remains, of course – not a monument but a more ordinary town, still a good place to live for many though wrestling with problems common to all. But perhaps the idea it represented has – for the moment – died.

Sources

(1) Robert B Black, The British New Towns – A Case Study of Stevenage, Land Economics, Vol. 27, No. 1, February 1951

(2) Quoted in Gary Younge, ‘Stevenage’, Granta, Issue 119, Spring 2012

(3) Quoted in Frederic J. Osborn and Arnold Whittick, The New Towns. The Answer to Megalopolis (1963)

(4) University of Westminster and the Leverhulme Trust, Construction Workers in Stevenage, 1950-1970 (2011)

(5) Osborn and Whittick, The New Towns. The Answer to Megalopolis

(6) Gary Younge, ‘Stevenage’

Stevenage was, and is, a truly remarkable vision. My parents were Stevenage ‘pioneers’ moving here in 1954 and I was lucky enough to grow up here. I love this sentence above ‘But it contains an essential decency and sense of community – nothing saccharine or pious, a simple responsibility of one for the other’, it sums up our very special community in Stevenage, a community which still has the co-operative spirit which developed in those early years. I hope the idea the new towns represented has not died, those of us who were lucky enough to grow up here like Gary Younge and myself have a responsibility to keep it alive!

Thanks for the comment, Sharon – it’s great to hear that that community and the dream lives on. I know you’re doing your bit.

Loving Sharon’s comment about ‘the co-operative spirit’ – I work for The Wine Society, a co-operative business owned by it’s customers, or members. We moved to Stevenage in 1965.

Is this the last post on ‘Municipal Dreams’? It reads like an elegy. I have loved reading about these pioneering community experiments. I have learned so much about social history and the dreams of ordinary people and dedicated activists from this blog. But it’s also shown me how blogging can make history come alive. That will be a good legacy for the blog! But, if this is the last post, I will miss Municipal Dreams!

Thank you but I’ll be back next week – though now I’m thinking I should retire on the high note of your generous comment!

The setting of course for the ‘groovy’ 1967 film ‘Here we go ’round the Mulberry Bush’ starring Barry Evans. Many of these spaces were quasi-Radburn in their planning, separating the car from the pedestrian as you suggest. Such wonderful, hopeful, progressive stuff – a spirit which has almost been entirely wiped away in recent years.

BTW – be careful with CreateStreets – neo-liberal social cleansers and land grabbers acting as ‘concerned’ commentators on ‘how we live today’ in my opinion.

A great piece. The cycleways were most certainly pioneering but because Stevenage’s transport planners made the town so friendly to cars the infrastructure was woefully under-used. I wrote a long and detailed piece on Eric Claxton’s dream: http://www.roadswerenotbuiltforcars.com/stevenage/

I first learned about New Towns on an extra-mural Sociology course at Westminster College. Later, married and with two children and living in Notting Hill on a teacher’s salary, owning my own home seemed an impossible dream. Having secured an alternative job in Stevenage in 1967, our move from a damp basement in Kensington to a terrace house and garden in Oaks Cross, Broadwater was a massive improvement in lifestyle and life chances for my wife Elisabeth and our two girls, Caitlin and Jane. Even though my salary as Playworker in Charge of Bandley Hill Adventure Playground was less than in London in a year or two I was able to get a mortgage and begin to purchase a decent place to live for the first time since I arrived from New Zealand in 1956. The opportunities that Stevenage provided were a gateway to even bigger things, culminating in an job with Peterborough Development Corporation in 1970. I feel that the high ideals that lay behind the New Towns were about as well achieved as any ideals can be and deplore and detest the actions of Margaret Thatcher and her hideous crew, who pulled the plug on the whole programme. This included Peterborough Development Corporation, which was not allowed to build its planned final stage which should have housed 10,000 people in homes that are desperately needed today. Readers may wish to know that the whole archive of PDC is now housed in Peterborough Central Library thanks to the programme known as 40 years on.

Thanks for taking the time to share your story. It’s interesting that this is the blog entry which has attracted most comments. Contrary to what people might think, Stevenage seems to inspire affection.

I’ll bear Peterborough in mind too.

Pingback: The sad tale of a cycle network innovator forgotten by the New Town he built - Roads Were Not Built For Cars

Pingback: Early Municipal Housing in Birmingham and the ‘prejudice against flats’, Part 1 | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Social Housing under Threat: Keep it ‘affordable, flourishing and fair’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The County of London Plan, 1943: ‘this new world foreshadowed’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Lansbury Estate, Poplar, Part 1: meeting ‘the needs of the people’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: “Something better than soulless suburbia”: Cwmbran New Town | Other formats are available

Pingback: Memory Lane. Day 20. #30 Days Wild | a daily dose of nature

Pingback: Harlow New Town: ‘Too good to be true’? | Municipal Dreams

My parents moved to Stevenage around 1953 and originally lived in Rockingham Way. My father came from Durham and during his wartime service in Italy married my mother. After the war they came back to the North East but my mum couldn’t stand the cold up there, so they moved to North London, and from there to the new town of Stevenage. My dad worked at English Electric (later BAC and British Aerospace) as did my mum.

Moved to Popple Way where I grew up.

Had a great time during my younger years attending Fairlands schools and latterly Heathcote School.

Pingback: Thetford: ‘A Town Which Has Picked Expansion’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Book Review: Jon Lawrence, Me, Me, Me: The Search for Community in Post-war England | Municipal Dreams