Tags

We left Thetford a few weeks back in 1939, in a parlous state; both, to quote from that post, ‘a sleepy rural backwater’ and ‘a long-established borough with urban pretensions and ambitions’.

In the first instance and in the context of the post-war housing drive, those ambitions were met by a renewed council housebuilding programme. Forty new homes were added to St Mary’s Estate, completed just before the outbreak of war, in the late 1940s and further new housing in the 1950s. By 1958, Thetford had built some 448 council homes and they formed almost 35 percent of the town’s housing stock. (1) The town’s population stood at a little over 4600.

An image of old Thetford: King Street in the 1950s © Archant

But fundamental problems remained: (2)

the town had come to a point where continued existence as an independent unit was hardly feasible. Firstly the population of the town had decreased; secondly the community began to lose its youth as they sought jobs and a fuller life elsewhere; and thirdly the rating load was becoming unbearable.

Thetford had to expand. And it seemed that the Council’s Town Development Committee set up in 1952 might just be knocking on an open door. A prime goal of post-war planning – anticipated in the 1940 Barlow Report on the Distribution of Industrial Population and the 1943 County of London Plan – had been the dispersal of population from London. The first means to this objective had been Labour’s 1946 New Towns Act (responsible for the creation of Stevenage and Harlow, amongst others) but an uncontrolled growth in the service sector and a rising birth rate had mitigated its impact. An incoming Conservative Government was, in any case, unsympathetic to what they saw as the heavy-handed statism of such an approach.

A map showing new and expanded towns in the south-east

In 1952, legislation was passed ‘to encourage Town Development in County districts for the relief of congestion and overpopulation elsewhere’. Thetford’s initial approach to the London County Council (LCC) in 1953, proposing to receive some 10,000 Londoners, was rebuffed. A modified scheme, taking in some 5000, was suggested in 1955 but came to naught.

Its small-town air and distance from the capital may have hindered Thetford’s appeal but it held certain advantages, notably the existence of a single large landowner (the Crown) to aid expansion and its proximity to North Sea ports. Perhaps Thetford’s greatest asset, however, was its neediness – its desire for expansion: (3)

Legend has it that what finally won over the hearts of the London councillors was a plea by a Thetford woman councillor that ‘even taking on another dustman meant putting sixpence on the rates’.

London, in the meantime, was still committed to downsizing by the transfer of around 250,000 of its population and 400 acres of industry to new and expanded towns beyond the Green Belt in the late 1950s. (4) Finally, in May 1957, agreement was reached. Thetford, the receiving authority under the 1952 Town Development Act, would agree to the LCC, acting as its agent, building some 1500 homes to house around 5000 moving from the capital.

Moving this story forward before looking in detail at its lived reality, these push-pull factors continued to operate. By 1959, the Norfolk County Council was committed to a population for Thetford of 17,000 by 1980 with 60 percent representing an overspill population. The Borough Council and LCC themselves agreed an additional 5000 population transfer in 1960. The Government’s South-East Study, published in 1964, tasked the new Greater London Council with moving 110,000 families to Expanded Towns by 1981. (5)

By 1978, 3500 council homes had been built in Thetford in twenty years; they comprised near two-thirds of its housing stock. In 1981, its population stood at 21,000. These people needed jobs and another vital component of Thetford’s expansion was its ability to attract new employment.

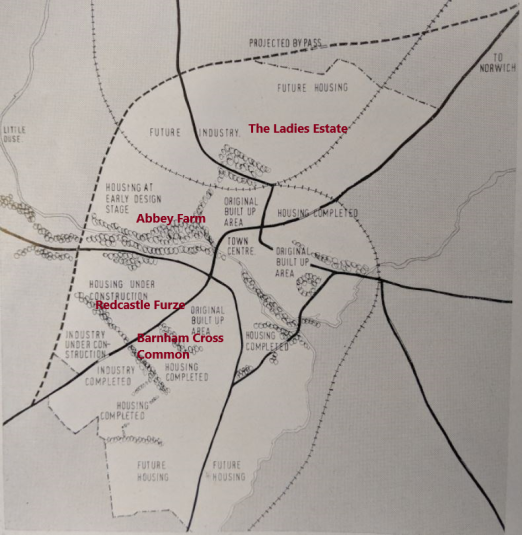

A map from the mid-1960s with estate locations added

There were benefits to the move to Norfolk. For workers, the Industrial Selection Scheme inaugurated in 1953, guaranteed some on the LCC’s council housing waiting list both a job and a home. For companies, there was the lure of better (and cheaper) purpose-built factories and a relatively lower-paid workforce. (Skilled workers moving with London-based firms generally continued to receive London rates; those on the Industrial Selection Scheme fared less well.)

But there were difficulties too: (6)

It was found impossible to convince … early enquirers of the advantages of making this move, when there was nothing to show them but fields of poor quality sugar beet and some pretty coloured drawings.

And some initial encouragement was required. In the end, the Borough Council kick-started the process by building and leasing two factories of its own. By 1966, there were 46 companies established in Thetford. Around 52 percent of the local workforce worked in the manufacturing sector with no firm employing over 200. This diverse economy was considered a plus given the catastrophic impact of the closure of the town’s single large employer in 1928. (7) The larger manufacturers included such household names as Conran, Danepak, Thermos and, from the late 1960s, Jeyes, which had moved from East London. That initial investment had paid off generously; by November 1973, 70 council-owned factories brought in rents of £176,000 a year and a penny rate was worth £20,000. (8)

An early photograph of Barnham Cross Common

Back in time, the first house on the first overspill estate in Barnham Cross Common (appropriately off London Road to the south-west of the town centre) was officially opened in April 1959. Almost 300 new homes were completed by 1961: (9)

The first two or three hundred families who moved in were very much in the nature of pioneers, living on estates which did not have a bus service into town, no community centre, and where the shopping parade on the estate … had not been completed.

The shops on Pine Close opened the following year.

The shops on Pine Close, Barnham Cross Common

Barnham Cross Common was a conventional estate of its time – existing belts of trees in the Breckland landscape characteristic of the area were retained; the houses themselves were conventional brick-built, two-storey homes built facing service roads around small greens and grassed courts. The finished estate comprised 877 homes and – a sign of the times – 523 garages.

An aerial shot of the Redcastle Furze Estate in 1972, showing the Radburn layout

An early photograph of the Redcastle Furze Estate

Planning for a new estate across the road began in 1963 which would eventually, after 1970, provide another 800 homes. The Redcastle Furze Estate was a very different animal, incorporating the Radburn principles (separating traffic and pedestrians) now in vogue.

‘Anglia Houses’ under construction by Taylor Woodrow, Redcastle Furze Estate

Completed ‘Anglia Houses’, Redcastle Furze Estate

Some of the homes, reflecting another fashion of the era, were prefabricated. The Greater London Council’s ‘Anglia Houses’ were made of concrete crosswalls, supplied in up to four units, as well as factory-made timber panels forming roofs and internal partitions. Timber cladding panels were also supplied. The intention was to minimise on-site work and the system, though designed for terraces, allowed variations in internal design and overall layout. (10)

An estate plan of Abbey Farm

The final, major estate – Abbey Farm – was commenced in May 1967 and completed in February 1971. It represented a further evolution in design. Initial plans for a Radburn-style layout were abandoned: (11)

Early experience with the Redcastle Furze Estate indicated that although this type of layout had much to commend it, it had some drawbacks, e.g. visitors found difficulty in finding their way around, and thought was given to improvement that could be made in the layout at Abbey Farm.

Abbey Farm maisonettes, rear

Abbey Farm townhouses

Instead the estate was equipped with a large spinal road, Canterbury Way, running through its centre. Large four-storey maisonette blocks were laid out this main road while narrow-frontage two- and three-storey houses, mostly with inbuilt garages were laid out along small cul-de-sacs leading off it. The Housing Minister, Anthony Greenwood, visiting the estate in July 1968, declared the layout and design of the homes ‘exceptional’ and the best he had seen. (12)

The Ladies Estate

One other significant scheme remains: the so-called Ladies Estate, begun in 1974 and completed in 1979. Elizabeth Watling Close and Sybil Wheeler Way commemorated two former mayors of the town; Boadicea, Edith Cavell and Elizabeth Fry were among other local female notables celebrated. The 560 low-rise brick-built houses, bungalows and flats and curving streetscape created an attractive though undeniably suburban ensemble.

By 1979, Thetford had been transformed, by any objective measure, from its mid-century Slough of Despond into a successful and bustling expanded town. The next post examines how this shift played out, both for existing locals and the many thousands of incomers. We’ll see too how far this apparent early promise has been fulfilled.

Sources

(1) Greater London Council, Department of Architecture and Civic Design, ‘Thetford: Case Study in Town Development’ (March 1970); DG/TD/2/96, London Metropolitan Archives

(2) John Gretton, ‘Out of London’, New Society, 15 April 1971

(3) Gretton, ‘Out of London’. A 1973 article was headlined appropriately ‘Thetford: a Town which has Picked Expansion’ (Built Environment, March 1973)

(4) ‘Town Expansion Scheme at Thetford’, The Surveyor, vol CXVI, no 3415, 5 October 1957

(5) Peter Jones (Town Development Division, GLC), ‘The Expansion of Thetford’, Era: the journal of the Eastern Region of the Royal Institute of British Architects, vol 1, no 4, August 1968, pp34-40

(6) WRF Jennings (Borough Engineer and Surveyor, Thetford), ‘Some Aspects of the Expansion of a Small Town’ [ND c1966]

(7) Jennings, ‘Some Aspects of the Expansion of a Small Town’ and Greater London Council, Department of Architecture and Civic Design, ‘Thetford: Case Study in Town Development’

(8) Michael Pollitt, ‘William Ellis Clarke, MBE: ”Mr Thetford”: one of the architects who shaped the modern face of the town’, Eastern Daily Press, 9 January 2014

(9) Peter Jones, ‘The Expansion of Thetford’

(10) ‘Expanding Towns: Thetford, Norfolk,’ Official Architecture and Planning, Vol. 30, No. 10 (October 1967)

(11) Thetford Borough Council and Greater London Council, ‘Abbey Farm Housing Estate’ DG/TD/2/93, London Metropolitan Archives

(12) GLC Press Office, ‘Thetford Homes’ – “Best I have seen” says Minister’, 10 July 1968

An early photograph of the Redcastle Furze Estate, is actually the Abbey Farm Estate

Pingback: Thetford: ‘A Town Which Has Picked Expansion’ — Municipal Dreams | Old School Garden

Pingback: ‘The London Borough of Thetford’? | Municipal Dreams

H

i Can you tell me were the above comments were made ,The Earlier Experience with Red castle Furze , and the commnet by Anthony Greenwood , housing minister , about Abbey Farm , he said it was the best he has ever seem ,

Best regards

Stephen Bartrup stephenbartrup@yahoo.co.uk

Apologies again for the Contact Me button not working. You can email directly to municipaldreams@outlook.com. Re the Redcastle Furze quote, that is also found in the London Metropolitan Archives: DG/TD/2/93, ‘Thetford Borough Council and Greater London Council, Abbey Farm Housing Estate’ to be precise. Feel free to get back in contact if I can help further. John

Hi Thanks for info trying the london metropolitan archives , good fun on this website

Hi John, this is really interesting, thank you. I’m researching expanding towns for some background info on something else, but it’s proving a little tricky online at the moment. I was wondering if you knew when the programme was brought to an end? LMA document dates suggest 1979 but I’d be really interested to know for sure.

Many thanks, Tess

Hi Tess, I didn’t have an immediate answer though 1979 sounded about right. I ended up doing some online research, as you have, and from a range of sources it seems you can date the *effective* end of the programme to 1976 when the Labour Government shifted policy towards inner city regeneration – a policy subsequently pursued in its own way by the Thatcher government. My sense is that the programme withered away as much as it was formally abolished (and I’ve seen no reference to the latter). This article (p16) pretty much makes that case.

Click to access osp1.pdf

I hope that – not definitive – response is some help. All the best, John

Really helpful – thanks very much indeed!

Sorry, that should have been p14.

Pingback: Council Housing in Thetford before 1939: No ‘borough as small had done more’ | Municipal Dreams