In early October, I was invited by John Aitken and Jane Brake of the Institute of Urban Dreaming to visit the Pendleton Estate in Salford, one a number of people who have visited. We were asked to provide a response to the experience and an impression of the estate. These will feature, along with the archive of documentation accumulated by John and Jane during their long years of residency in the estate, in an exhibition at the People’s History Museum running from 29 October 2016 to 15 January 2017.

The post which follows represents what might be called a prehistory of the estate – looking at the housing it replaced, the ideas behind the huge redevelopment which took place in the sixties, and the questions of community raised by each.

…streets, mazes, jungles of tiny houses cramped and huddled together, two rooms above and two below; in some cases, only one room alow and aloft; public houses by the score where forgetfulness lurks in a mug; pawnshops by the dozen where you can raise the wind to buy forgetfulness; churches, chapels and unpretentious mission halls where God is praised; nude, black patches of land, “crofts”, as they are called, waterlogged, sterile, bleak and chill.

Walter Greenwood cast an unsparing eye on the Salford he grew up in and knew so well. (1) He was brought up on Ellor Street in Pendleton, the only son of a master hairdresser and educated at the local Langworthy Road Primary School. His schooling ended aged thirteen; he’d worked outside school hours as a pawnbroker’s clerk twelve months previously and would go on to experience a range of other menial jobs as well as periods of unemployment before writing Love on the Dole, published in 1933.

56 Ellor Street, Greenwood’s birthplace, shown empty and derelict in the 1960s (c) WGC4-4-2, Salford University Library, Archives and Special Collections

The book’s protagonist, Harry Hardcastle, unwisely forsakes his ‘soft’ office job as just such a pawnbroker’s clerk to become as an apprentice at ‘Marlowe’s’, a local engineering works – man’s work to Harry but after seven years, his time served, Harry is laid off just as the men preceding him had been as the Great Depression hit. The props – a living wage (just) and the dignity of work – which might have made his harsh environs endurable are removed and the squalor of the mean slum terraces and abject lives they spawned exact their toll.

Greenwood wasn’t writing for effect and his novel – working men and women and those without work are its heroes – is a world away from the poverty porn which disfigures contemporary attitudes towards the poor.

Concerned middle-class observers such as the Manchester Social Service Group of the [Christian] Auxiliary Movement echoed his description of local conditions: (2)

Tall factory buildings pollute the air with smoke and block out sunshine and light, so that many householders have to burn gas all day. Not a single house has a garden and all are grimy with soot. There is no recreation ground, although small vacant plots, dusty, often littered with refuse, and absolutely devoid of grass, are sometimes used for this purpose.

The corner of Florin Street and Douglas Street in the 1960s (c) WCG4-4-3, Salford University Library, Archives and Special Collections

They surveyed the Chapel Street/Blackfriars Road area of Salford two miles east of Hanky Park (nicknamed after the main local thoroughfare, Hankinson Street) where Greenwood set Love on the Dole. Of some 500 houses, only four had baths and all, or very nearly all, needless to say, shared (outside) toilets. On the other hand:

As is found in other poor districts, the shops catering for wants rather than needs are surprisingly numerous. The section first mentioned contains six public houses, five supper bars, and five shops selling sweets and tobacco.

Our modern-day critics might make something of that wasteful spending on fripperies but one senses here something more sympathetic – a realisation that hard lives needed something softer to make them bearable.

The E Griffiths Hughes Chemical Works, the Adelphi Iron Works and environs, Salford, 1934 (c) Historical England EPW045058

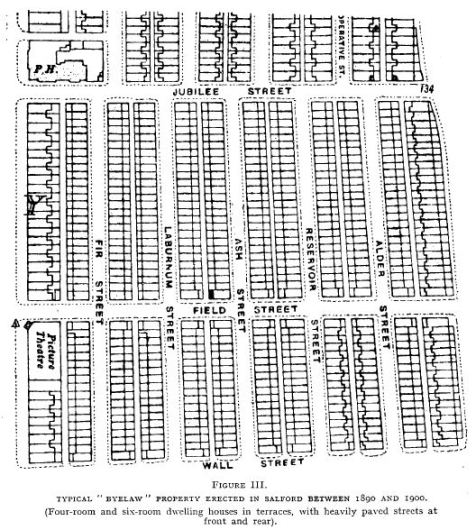

Local government provided a more bureaucratic but more statistically telling account of local living conditions thirteen years later. In the 50,500-odd homes of the County Borough of Salford (it had, of course, its more salubrious middle-class suburbs), over half lacked hot water; almost one in five were judged ‘totally unfit and scheduled for early demolition’, one in ten ‘other unfit homes’ were slated for later demolition. Of the rest, 24,500 were substandard – too good for demolition but still, nevertheless, falling ‘below reasonably fit standard’. JE Blease, a Salford sanitary inspector, pointed out that these obsolescent terraces were the late Victorian byelaw housing ‘heralded with pride’ for their sanitary improvements ‘by building surveyors some sixty years ago as an approach to the artisan’s utopia’. (3)

We’ve arrived at 1943 in a world at war – a war which made those redundant working-class male bodies of the thirties valuable once more, either in military service or on the home front in war production. We can be cynical about a society which places a premium on human lives which it is otherwise busy destroying but there were, during this second world war, other more humane and progressive forces at play.

In this context, the first film version of Love on the Dole in 1941 might initially seem surprising. What more searing indictment of Britain’s class-ridden and socially unjust society could there be? For this reason, the censors were initially reluctant to authorise its production (they deemed it ‘a very sordid story in a very sordid surrounding’) and yet the director John Baxter, was, for his part, determined that the film should ‘not be a star-vehicle because it should represent ordinary people’. (4) (Deborah Kerr who played Harry’s sister, Sally, would make her name later.)

In this context, the first film version of Love on the Dole in 1941 might initially seem surprising. What more searing indictment of Britain’s class-ridden and socially unjust society could there be? For this reason, the censors were initially reluctant to authorise its production (they deemed it ‘a very sordid story in a very sordid surrounding’) and yet the director John Baxter, was, for his part, determined that the film should ‘not be a star-vehicle because it should represent ordinary people’. (4) (Deborah Kerr who played Harry’s sister, Sally, would make her name later.)

There was a significant shift, however. John Harris notes a ‘doughty, optimistic dialogue that was not in the novel’ and the film (unlike the book) ends on a positive note with the parting words of Harry’s mother:

One day we’ll all be wanted. The men who’ve forgotten how to work, and the young ‘uns who’ve never had a job. There must be no Hanky Park, no more.

Greenwood must surely have approved. Some of his early mentors had been working-class activists and much of the novel had been written at Ashfield Labour Club in Salford. Greenwood himself was briefly – he wasn’t cut out for active politics himself – a Labour councillor. In a later interview, he stated his novel’s purpose in showing ‘what life means to a young man living under the shadow of the dole, the tragedy of a lost generation who are denied consummation, in decency, of the natural hopes and desires of youth’.

Greenwood must surely have approved. Some of his early mentors had been working-class activists and much of the novel had been written at Ashfield Labour Club in Salford. Greenwood himself was briefly – he wasn’t cut out for active politics himself – a Labour councillor. In a later interview, he stated his novel’s purpose in showing ‘what life means to a young man living under the shadow of the dole, the tragedy of a lost generation who are denied consummation, in decency, of the natural hopes and desires of youth’.

In this 1941 iteration, Love on the Dole was an emphatic ‘never again’ – both a demand and, implicitly, a promise of a better post-war world.

Again, the rhetoric of local government was drier but its planners believed their craft and vision central to this new world and saw planning, humane and rational, as the very antithesis of the destructive anarchy wrought by the free market.

In February 1942 Salford’s City Engineer, W Albert Walker, emphasised that the ‘central concern’ of town planning was ‘the health, happiness and well-being of the people’. ‘The very starkness in which we have now seen the defects’, he continued, ‘may arouse new interest with a fresh determination that prevailing conditions must be improved’. (5)

The Beveridge Report, a 1943 best-seller

Nationally, the Beveridge Report published ten months after Walker’s Salford speech promised to slay the five ‘Giant Evils’ – Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness – which so straitened the lives of the Salford working class Greenwood portrayed. The Report sold 630,000 copies. Many obviously shared Mrs Hardcastle’s hopes for the future.

But if all this was a revolution, it was a very British one. Beveridge himself emphasised that his great scheme of social security was ‘first and foremost, a plan of insurance – of giving in return for contributions benefits up to subsistence level’ (though, crucially, without the Means Test which scarred the family lives of Greenwood’s protagonists).

In housing (the ‘Squalor’ that Beveridge attacked), there were similarly pragmatic proposals. Mr Blease suggested that much of the borough’s terraced housing could be reconditioned. However, his helpful sixteen point checklist of required improvements – covering roofs and guttering, windows and doors and much else beyond the now bare essentials of baths and toilets – suggested the difficulty. ‘The desired up-grading of substandard houses will not be accomplished by philanthropic enthusiasm on the part of landlords’, he commented mildly; nor could it be funded under existing local government powers.

An illustration of bye-law housing drawn from JE Blease, ‘The Unfit House’. This area is now the site of Urban Splash’s radical redesign of these traditional terraces.

Labour’s 1949 Housing Act did, in fact, allow local authorities to acquire homes for improvement or conversion with 75 per cent Exchequer grants but this was not yet the approach prioritised by central or local government.

City Engineer Walker spoke to higher ambitions: for ‘large agglomerations…there must be satellite towns. When a central area is re-developed, there must be a reduction in density’. He was far more sceptical about high-rise construction:

There appears to be no reason or excuse for blocks of flats in the average town of one hundred thousand population or under. There is an attraction about erecting a large block of buildings. They look compact and tidy. The proportion of the site built up may be kept low. But how will they be classed in, say, forty years? In the large urban aggregations to which reference has been made, flats will no doubt find a place, but they are only the next best thing to good houses.

We’ll just let those comments stand. To many, they might seem an almost uncannily prescient anticipation of a debate that had erupted fiercely in the four decades which Walker prescribed.

At first, Salford followed Walker’s advice with the creation of a large overspill estate in the then Urban District of Worsley some eight miles to the west of Salford’s historic centre. Inaugurated in 1949, the Salford-Worsley scheme had, by 1959, relocated almost 10,000 (of a projected 17,000) Salfordians. In the fifties, the Borough proposed moving almost a quarter of its population (40,000 of 178,000) to greenfield sites beyond its borders. (6)

Overspill housing in Little Hulton, part of the Worsley scheme (c) Eccles and District Local History Society, www.hultonhistory.btck.co.uk/Memories/Salfordoverspill

Such a shift was not without problems for those involved. The new council rents were, on average, three times higher than those paid previously. Seven in ten of the estate’s workforce commuted – one and half hours there and back – to Salford for work. And then, according to the planner JB Cullingworth, there were added expenses caused by a new ‘social necessity to “keep up appearances”’.

Ten per cent of families returned to Salford; in Cullingworth’s survey, three-quarters would have returned if only they ‘could obtain accommodation in Salford which was of “the Worsley standard”’. There lay the rub, of course:

Over a quarter of the families have moved from shared and overcrowded houses; a further third had previously lived in damp and obsolescent accommodation. Their present living conditions form a most striking and welcome contrast.

So most settled and, in time, a new community would develop. It would, however, be a very different community from that described by Greenwood. Cullingworth, in a single sentence, captures the shift which some contemporary observers decried: ‘The intimate life of the slums has given way to the more reserved, home-centred life of the typical middle-class suburb’.

Writing of the new out-of-county estates of the London County Council, Peter Willmott and Michael Young lamented the loss of ‘the sociable squash of people and houses, workshops and lorries’ that had made up the old East End and mourned, in particular, the break-up of the matriarchal kinship networks they held to have previously sustained community life. (7) They’ve been criticised since for a selective use of evidence and a much romanticised view of slum living.

Greenwood is a corrective here and Cullingworth himself offered a far more sardonic take:

Separation from ‘Mum’ has not been the hardship which some sociologists have led us to expect; on the contrary it has often allowed a more harmonious relationship to be established. The possession of a house in which pride can be taken has resulted in a closer and more intimate family life: activities are now centred on the home, the garden and the television set.

Contrary to much conventional wisdom, this was an escape from the pub to be celebrated, not the escape to it required by previously inhospitable home conditions.

The charge – it was usually a lament or criticism – of embourgeoisement (the view that working people were adopting middle-class lifestyles and values) is a more interesting one. For all the practical difficulties, Cullingworth found that the ‘majority of families were thrilled with their new way of life’. Perhaps, therefore, we should recast this argument.

A image of the new affluence: the new Salford shopping precinct as imaged in the Report on the Plan

Are we really saying that as soon as the working class achieve decent living standards that they have thereby become middle-class? Sometimes it seems that way; sometimes it seems that some left-wing commentators would prefer the working class to be ‘poor but happy’ (or even unhappy if that better maintained a purer and more militant proletarian politics). Let’s just scrap the labels which seem to affix too readily essentialist class attributes to certain modes of living. Besides the definitive study of the so-called ‘affluent worker’ found that, despite their more ‘privatised’ home life, their working lives remained distinct and harder and their politics largely unaltered. (8)

Still, there was truth in Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s statement in 1957 that ‘most of our people have never had it so good’. This was an era of full employment and rising living standards. It seemed a tectonic shift; Love on the Dole was an historic record, a reminder of a lost world, one not to be repeated.

The new world was represented in the redevelopment of the Ellor Street area first approved by the Municipal Borough in 1960. In the words of Albert Jones, the chair of the Council’s Planning and Development Committee, ‘we may be thirty years late but we are trying now to obliterate Hanky Park as it was known and propose to make the area something of which we can be proud’. (9)

The bare bones of the plan were to clear 89 acres of land in which, according to Jones, ‘three thousand families lived in slum conditions as bad as any to be found in the country’. (10) But the form of redevelopment was peculiar to its time.

In March 1961, the Council commissioned Sir Robert Matthew, formerly Chief Architect to the London County Council and now Professor of Architecture at Edinburgh University, to act as consultant. His plan, prepared in collaboration with architect-planner Percy Johnson-Marshall, director of the University’s Housing Research Unit, envisaged something far more sweeping than the mere replacement of substandard housing.

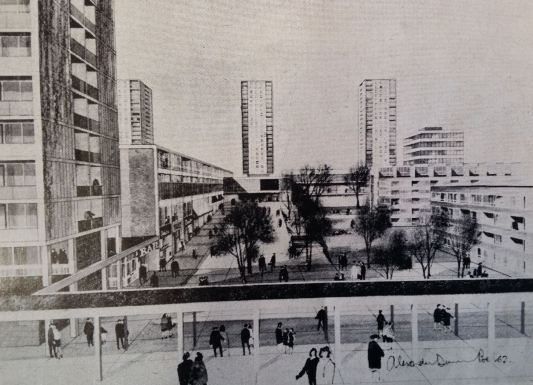

The project was seen ‘strategically as a vital part of the regeneration of the industrial north of England’; its aim ‘to recreate within the Greater Manchester Region a city centre which will make for a high standard of environment in terms of living, shopping and civic affairs, using the latest techniques of planning and development to fit the new centre for the motor age’. (11)

Matthews continued, in the Report on the Plan which would form the template of the finished project:

The basic idea of the scheme is to provide a beautiful and spacious environment with large and continuous pedestrian space over a large area so that the citizens of the new Salford may drive off efficiently to work or else walk down a new parkway right into one of Europe’s finest shopping centres without having to cross any roads.

Much of the proposal therefore features what was planned as a combined Civic and Shopping Centre – the former containing a new town hall, library, and museum and art gallery as well as what was billed as a ‘contemporary Trafalgar Square’ for the borough; the latter, 400,000 square feet of retail space as well as parking for 2070 cars. The adjacent A6 was to be brought up to motorway standard to aid traffic flow.

‘View looking eastward along the main pedestrian way’ (Broadwalk from the shopping precinct) as envisaged in The Report on the Plan

Practically, this spoke to Colin Buchanan’s influential report, Traffic in Towns, published in 1963. It was designed to manage the problems caused by increased car ownership and enhance the quality of urban life – there were 10.5 million vehicles registered in Britain at the time but the figure was expected to almost double by the end of the decade. It was the report’s support for urban motorways, however, which, as implemented, blighted a number of city centres that have secured its hold in the popular imagination.

Ideologically, the plan reflected the sense that a modern and prosperous Britain was emerging, one whose promise extended to a working class, more securely employed and better-off than ever before. In this context, Hanky Park did, indeed, seem a remnant of a benighted past.

A 1961 concept model of the new estate

‘Forward to the City Beautiful!’ proclaimed one Salford newspaper headline of 1961 and the plan was claimed by its boosters as vital to the borough’s renaissance. One Salford councillor asserted that ‘our future as a city stands or falls by Ellor Street’ – the redevelopment would ‘add 2800 families to our population, revitalise our trade, and give our rateable value its first boost since the war’.

There, of course, was represented another aspect of the scheme’s appeal. Salford, like other similarly placed towns and cities, had turned against the large-scale decanting of its population to distant and beyond-border estates. The latter had, as we’ve seen, its practical problems for the new suburbanites but there was a fear too that the local authorities themselves were – literally and metaphorically – diminished by the loss of population the policy created.

Aerial view of the Ellor Street Redevelopment Area, c.1964 (c) Salford University Library, Archives and Special Collections

The new housing, therefore, wasn’t – though it is discussed in the concluding section of the Report on the Plan – exactly an afterthought but it was covered rather summarily. ‘Immediate housing requirements have been met by siting three 15 storey blocks on the north-west corner of the site’, it stated. For the rest, it proposed mainly eight-storey maisonette blocks, some four-storey, eight unit blocks providing family houses and, rather casually, three twenty-two storey point blocks and other 16-storey blocks which would ‘give emphasis and continuity to the visual sequence of the development’.

This was, to say the least, a sharp break from the two-storey terraces which had dominated previously and a clear contrast with the more cautious approach suggested by that wartime generation of planners discussed earlier. But it reflected the wisdom of the age that assumed high-rise construction offered a quick and easy means to provide both the new housing and urban density required by the new wave of slum clearance.

The Ellor Street redevelopment Stage 8 (c) Glendinning and Muthesius, Tower Block (1984)

By some accounts, the residents of Ellor Street and surrounds, those who would inhabit the brave new world created by the planners and politicians, were less sure of the solutions proposed. One local journalist observed: (12)

It is a district of people whose roots are firmly embedded in the hard ground, and there is every sign that they are not going to take kindly to the sudden upheaval. There was a sense of uneasiness around, which is in many cases hidden by a joke or a resolution to face the new life – the sort of resolution one reaches when facing a visit to the dentist to have that worrying tooth removed.

It seems the stoicism deployed to survive the hardships of the thirties was required once more to cope with the benefits bestowed by modern affluence. We’ll see how all this played out in next week’s post.

Sources

(1) Walter Greenwood, Love on the Dole (1933)

(2) Manchester Social Service Group of the Auxiliary Movement, No. 9 Report on a Survey of Housing Conditions in the Salford Area (Manchester, Sherratt and Hughes, 1930)

(3) JE Blease (Sanitary Inspector, Salford), ‘The Unfit House’, The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, vol. 66, January 1946, pp11-18

(4) The British Board of Film Classification is quoted in John Harris, ‘Rereading: Love on the Dole by Walter Greenwood’, The Guardian, 7 August 2010, and John Baxter in Chris Hopkins, ‘Why Love on the Dole stands the test of time’, 20 January, 2016

(5) W Albert Walker, ‘Post-War Housing Development’, Read at a Sessional Meeting held at Salford on February 14th, 1942; The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, vol 62, April 1942, pp75-84

(6) JB Cullingworth, ‘Overspill in South East Lancashire: The Salford-Worsley Scheme’, The Town Planning Review, vol. 30, no. 3, October, 1959, pp189-206

(7) Peter Willmott and Michael Young, Family and Kinship in East London (Routledge, 2013; first published 1957), p97

(8) John H Goldthorpe, David Lockwood et al., ‘The Affluent Worker and the Thesis of Embourgeoisement: Some Preliminary Research Findings’, Sociology, vol. 1 no. 1, January 1967, pp11-31

(9) Quoted in David Kynaston, Modernity Britain, 1957-62, (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015), p397

(10) Cllr Albert Jones, Foreword, in Robert Matthew and Percy Johnson-Marshall, Report on the Plan (Edinburgh: Bella Vista, 1963), p1

(11) Matthew and Johnson-Marshall, Report on the Plan p6. The quotation which follows comes from p7.

(12) Salford City Reporter, 3 April 1959 quoted in Kynaston, Modernity Britain, p289

Another excellent article from Municipal dreams a really informative account on the History of social housing I really liked your Bio of Greenwood and his Love on the Dole It shows how the great Reforming Labour Government of 1945 gave the working class a decent standard of Living and the welfare state and all that went with it. It was still a Reformist Labour Government during the Long Boom of the Fifties but it showed its Imperialist Colours with its foreign policy. A fine account I really enjoy your reports keep it up.

Laurence

Pingback: The Ellor Street Redevelopment Area, Salford: ‘No Hanky Park, no more’ — Municipal Dreams | Old School Garden

Pingback: The Pendleton Estate I: ‘A Salford of the Space Age’ or ‘Concrete Wasteland’? | Municipal Dreams

Many memories here.

Pingback: The Pendleton Estate, Salford II: ‘a distinctive neighbourhood with a strong identity’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Book Review: Jon Lawrence, Me, Me, Me: The Search for Community in Post-war England | Municipal Dreams

why did they have to build flats. Square little boxes for people to live in. bet you did not ask the PEOPLE what they wanted. A concret mess. with the heart ripet out of Salford.

Difficult to decide whether this is an attempt to justify what went “slightly wrong” as they see it or an apology for disastrous state intervention. Bearing in mind this was the age of C P Snow when technology would change the world for the better it wasn’t a unique concept

Also, the use of the term Hanky Park was, and remains, misleading. This was probably a mechanism, in the implementation stages of the project, to give momentum to an ill-founded utopian vision. In my recollection the only really bad area was around Rossall St and Earl St on the west side of Hankinson St only – a minor fragment of the blackened area bounded by Broad St in the north, High St in the south, Cross Lane in the east and Langworthy Rd in the west. Probably half the remaining properties were inferior by the standards of the time, but they could have been economically improved by knocking two into one as they are now doing in parts of Manchester- at least that’s an example of a lesson learned.

The reason Rossall St, Earl St etc, the real “Hanky Park” was a sink area, dirty, and decrepit, was because it was dominated by unemployed families who had dropped out of productive society, with more than its share of villains; totally different from the rest of the area; even immediately east of Hankinson St was a different socio-economic area altogether.

The phenomonen of Rossall St wasn’t unique it was present in limited areas of Broughton and Ordsall too; it wasn’t just Rossall St etc.

But the real problem wasn’t technical, it was the absence of any practical consideration of the socio-economic effects of a plan that resulted in the destruction, by scattering, of cohesive productive communities and the industrial base it supported.

Derek, Thank you for your thorough response. I’m happy to accept your detailed description of the area from someone who clearly knows it better than me. In terms of your wider critique, that seems to me to misunderstand the purpose of the post which, I believe was neither apologia nor defence but an attempt to offer a detached analysis, one understanding of the ideas and dynamics of the time but certainly not oblivious to contemporary criticisms or later problems. If you read the follow-up posts, you should have seen the latter fully discussed. The counterfactual you pose in the final paragraph must be moot given that the local economy and community were threatened by broader social and economic shifts that would likely have impacted adversely whatever the form of necessary rehabilitation or redevelopment that took place. John

Pingback: From Love on the Dole to Walter Greenwood Court - The Modern Backdrop

Pingback: Sky Children Come Down to Earth: The Rise and Fall of the Lower Kersal Estate | Municipal Dreams