Tags

Before the advent of a national health service in 1948, progressive local councils took their responsibilities towards the health of their people seriously. Nowhere was this more so than in the crowded inner-London borough of Bermondsey, not least because the leading figure of the local Labour movement was a local GP, the redoubtable Dr Alfred Salter.

We’ve seen this already in Bermondsey’s health propaganda and in its beautification schemes. Housing was, of course, another vital aspect of what can be truly called – in modern jargon – an holistic programme. The borough’s commitment to a ‘cottage home for every family’, exemplified in the Wilson Grove Estate, was intended to promote healthy living in every sense.

Today’s post looks at the more direct expression of the council’s healthcare agenda and, in particular, at what remains one of its most striking and heart-warming elements – its campaign against the local scourge of tuberculosis.

Such work depended not only on an idealistic and reforming council – Labour took control of Bermondsey in 1922 and secured its majority in succeeding elections – but on dedicated healthcare professionals. When Dr King Brown was appointed Medical Officer of Health in 1901, he joined a team comprising a part-time medical officer, a chief sanitary inspector, eight district inspectors, and three clerks.

When he retired twenty-six years later, his department was made up of five full-time medical officers, a full-time dental surgeon and part-time assistant, an inspectorate of fourteen, a staff of eight health visitors, nurses and other assistants for dispensary and dental work, plus clerks.(1)

Such elaborate healthcare needed premises. Following the 1918 Maternity and Child Welfare Act the Council opened its first mother and child clinic in 1920. Four others followed in rapid order.

Public baths and washhouses (for laundry) had been a feature of local council provision since the mid-nineteenth century but even in 1925 it was determined that only 150 houses in Bermondsey had fitted bathrooms. Typically the borough determined to provide the best public baths of their kind.

The Grange Road baths opened in 1927, with 1st and 2nd class swimming baths, 126 private baths, four baths for babies and Turkish and Russian vapour baths. A contemporary newspaper thundered against this ‘£150,000 Palace of Baths’ and its ‘Marble Halls and Stained Glass Windows and Turkish Baths That Few Can Afford’. They would, it claimed, have satisfied ‘even the most luxury-loving Roman patrician’.

He probably wouldn’t have used one of the eight rotary washing machines, four hydro-extractors or forty drying horses provided to do his own washing, however. Salter pointed out that the legislation required first and second-class provision and said he would have been happy to provide the baths free of charge had it been possible. Later, local pensioners and the unemployed were granted free use. (2)

The Council’s healthcare showpiece would be the new health centre promoted by King Brown’s successor, Donald Connan. The original £96,000 plans were scuppered by the refusal of loan support by the Ministry of Health and London County Council but the finished building – built at a cost of £44,125 and supported by the new Labour-controlled LCC after 1934 – remains impressive.

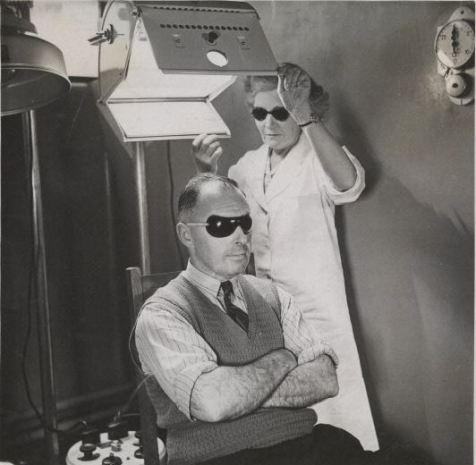

Designed by Borough Architect, Henry Tansley, the building opened in 1936 and contained infant welfare and ante-natal clinics, rooms for radiotherapy and diathermy (heat treatment using high-frequency electrical current), a foot clinic and a solarium and dispensary for sufferers of TB.

There was nothing glamorous about the treatment of ‘corns, callouses, bunions, in-growing and thickened toenails and warts’ but it was a vital service for a local workforce frequently on its feet all day and Bermondsey was the first council to provide it. The first clinic opened in 1930. Five years later, Bermondsey’s mayor, Cllr George Loveland, could look back sardonically on the amusement it caused, knowing that ‘whatever new social service Bermondsey started it was invariably successful and often copied elsewhere’. (3)

There was nothing funny about TB though. In the 1920s, 5500 local people had TB, there were around 400 new cases each year and 200 to 250 died annually from the disease. Almost half of those afflicted shared a bed and the council’s first endeavour was to provide backyard shelters for sufferers to sleep in.

There was nothing funny about TB though. In the 1920s, 5500 local people had TB, there were around 400 new cases each year and 200 to 250 died annually from the disease. Almost half of those afflicted shared a bed and the council’s first endeavour was to provide backyard shelters for sufferers to sleep in.

The council was determined to take a more proactive stance, however, and from 1924 the Council annually reserved six places in Dr Auguste Rollier’s pioneering Sun Clinic at Leysin in the Swiss Alps. Of Bermondsey’s first six patients, five went on to make a full recovery and many local people benefited from the treatment over the years.

But King Brown knew a larger-scale and more local service was needed also. In 1926, Bermondsey took over three houses and gardens in Grange Road as a Light Treatment Centre, equipped with eight large mercury vapour lamps, two carbon arc lams, one water-cooled Kromayer lamp and two radiant heat lamps. This was the first municipal solarium in Britain. In the first year, 562 cases were treated in almost 18,400 attendances – with immediate effect for new cases of TB fell from 413 in 1922 to 294 in 1927; deaths from 206 to 175.

Dr Connan would remark that:

Miserable ailing children, delicate, anaemic and flabby are being turned into plum, rosy-cheeked youngsters full of life and spirit.

And by 1935 there were 30,000 annual attendances and 30 lamps in use daily, supported by three dedicated nurses.

All this came at a cost. In 1931, Bermondsey spent £19,730 on maternity and child welfare – over one third more than that spent in the neighbouring boroughs of Camberwell and Southwark – and £36,877 on baths and washhouses – two thirds more than Camberwell. By 1938 the municipal debt stood at around £3m, compared to figures of £600,000 and £500,000 for Camberwell and Southwark respectively.

Still, the local newspaper could conclude: (4)

So great have been the improvements that many parts of the borough are unrecognisable as the slum areas of years ago, and so long as the ratepayers are prepared to pay for these improvements they can have no grievance against their Council.

In 1925, Alfred Salter had looked forward to turning Bermondsey into a:

New Jerusalem, whose citizens shall have reason to feel pride in their common possessions, in their civil patriotism, in their public spirit, in the joint sharing of burdens, and their collective effort to make happier the lot of every single dweller in their midst.

Times change.

Sources

(1) British Medical Journal, ‘Social Progress in Bermondsey’, Vol. 2, No. 3529 (Aug. 25, 1928)

(2) Fenner Brockway, Bermondsey Story: the Life of Alfred Salter, 1949

(3) Foreword to DM Connan, A History of the Public Health Department in Bermondsey, 1935

(4) This quotation, the one that follows and the preceding figures are provided in Sue Goss, Local Labour and Local Government. A study of changing interests, politics and policy in Southwark, 1919-1982, 1988

All the illustrations come with permission from Southwark’s excellent Local History Library. Do visit it to find out more about the history of this fascinating borough. Some images have been placed in the public domain by the Wellcome Trust.

Pingback: The Walworth Clinic, Southwark: ‘the Health of the People is the Highest Law’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Walworth Clinic, Southwark: ‘the Health of the People is the Highest Law’ - Socialist Health Association

Pingback: Solarium Court – A Southwark Blue Plaque Candidate | Running Past

Pingback: The Walworth Clinic, Southwark: ‘the Health of the People is the Highest Law’

Pingback: Ada and her garden village | The Gardens Trust