Finsbury Health Centre is not your usual obscure and unsung piece of municipal design. Even today, somewhat faded and hidden behind some rather overbearing vegetation, it looks something special. In its day, it was famously daring in both vision and design – in both its ideal of comprehensive, unified and free healthcare for all and in the bold architectural fulfilment of this ideal.

Finsbury was a typically overcrowded and poor inner London borough. But it was one with an unusually radical political history, rooted in the close-knit artisanal trades of the area. It elected its first Labour councillor in 1900 and Labour gained its first – bare – majority in 1928. Though the party lost heavily in the debacle of 1931, Labour regained – and retained – a secure hold on power in 1934. The council intended to use that power purposefully.

The driving figures in this were the council’s leader, Alderman Harold Riley, a local teacher descended from a Black Country mining family, and Councillor Chuni Lal Katial, a recent migrant from India, now a GP practising in the borough and chair of the public health committee.

The 1936 Public Health (London) Act empowered local authorities to provide medical services to their local population. Finsbury Council took up this challenge but aspired to more. Its Finsbury Plan outlined a far-reaching and coordinated strategy to elevate the conditions and well-being of the borough’s people. It included a health centre, baths, libraries and nurseries. Whilst war and financial difficulties prevented the entirety of that vision being fulfilled, the health centre was achieved triumphantly.

It was Katial himself who approached the modernist architectural firm of Tecton to devise plans for the clinic – the first public commission of a modernist design. Of the proposals submitted, the council selected the most expensive for its quality and space. The building was intended to live up to the maxim of its chief architect Berthold Lubetkin and the principles of its commissioners: ‘Nothing is too good for the workers’.

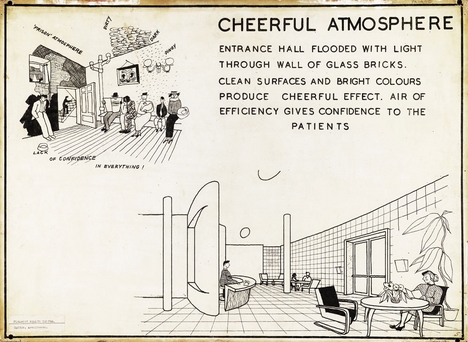

The illustrations below – part of the design outline provided by Tecton – contrast the ‘open planning’ ideals of the design to the heavy and rather overbearing architecture that typically preceded it.

Lubetkin believed the purpose of modern architecture was ‘to improve…the living conditions of the people, to create a language of architectural forms which…conveys the optimistic message of our time – the century of the common man’.

But his genius lay in the humanism of this ideal. The Centre was to be accessible and inviting, a drop-in centre before the term had been invented. For Lubetkin, ‘the centre’s opening arms and entrance were a deliberate attempt to introduce a smile into what is a machine’.

The brochure which marked the opening of the Centre, noted more dryly:

Care has been taken to give to the whole structure a light and clean appearance, to make it an edifice to the splendid service it represents; a building which will inspire confidence through its thoroughly modern and up to date appearance.

Glass bricks at the front entrance and side wings, red-painted columns, sky-blue ceilings, an open-plan reception – all were both practice and propaganda for a life lived more fully, more openly, more colourfully by a working population immured in poverty.

And if that wasn’t clear, murals on the wall exhorted the Centre’s users to ‘Live out of doors as much as you can’ and seek ‘Fresh air night and day’.

Finsbury’s ‘megaphone for health’ spoke loudly of a better, healthier life.

Practically, the Centre incorporated doctors’ surgeries, an antenatal and mother and baby clinic, TB clinic, chiropody clinic, dental surgery and solarium. The solarium provided ultraviolet-ray treatment to the children of the polluted and sun-starved borough – on chairs designed by Alvar Aalto.

The basement included facilities for cleaning and disinfecting bedclothes and a lecture theatre, even a mortuary for those past benefiting from the Centre’s services.

The Centre opened in 1938. Cllr Katial spoke to the thinking which inspired it:

For some time the disadvantages of a service which has grown up piecemeal, retarded in its development and scattered here and there through lack of accommodation, have been only too apparent to my council. Fully appreciating these difficulties, and actuated by a desire vastly to improve existing facilities and to establish new services, we have unanimously gone forward to erect this new health centre. Its opening marks…the dawn of a new era in public health service

It’s a dry, almost bureaucratic, language – the stuff that makes municipalism hard to sell and Municipal Dreams seem almost oxymoronic. But embrace that studied practicalism: it is precisely this realism and eschewal of rhetoric that changed lives. (It’s true, however, that Lubetkin always had the best lines. Those translucent glass walls seen above were intended to be ‘as beautiful as the hair of a beautiful young girl in the summer sunshine.’)

Barely a year later, Britain went to war and the Centre was pressed into service to meet the needs of more immediate casualties of man’s inhumanity to man but it was already an exemplar and a promise of a better tomorrow.

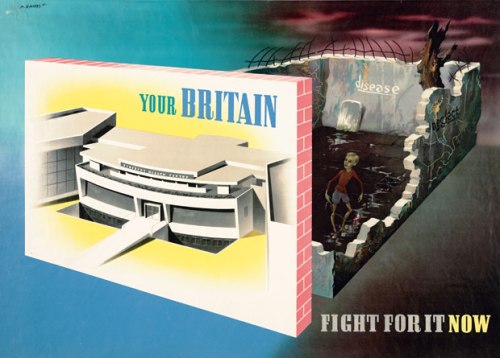

One year after the Beveridge Report itself seemed to herald that tomorrow and as the thoughts of ordinary people were already turning to winning the peace, in 1943 a poster was issued by the Army Bureau of Current Affairs which used the Finsbury Health Centre as its central symbol of the new postwar world.

In the event, the poster was deemed too radical. Churchill himself apparently considered its depiction of a child with rickets in a slum setting to be a ‘libel’ on working-class conditions. The poster was withdrawn but the aspirations which it represented that Churchill either feared or couldn’t comprehend were not so easily suppressed. Labour secured a landslide victory in the 1945 general election and the Finsbury Health Centre was to be a model for the National Health Service established three years later.

Today, it’s a Grade 1 listed building but it looks a little tired and that sparkling vision of municipal healthcare has been superseded. At the time of writing, it is still a local health centre but there have been plans to sell off the building and relocate its services. Opposition from local residents and architectural campaigners seem to have stalled these for the time being but the outcome remains uncertain.

What is certain is the practical idealism of the Centre’s creators. Their belief in an ethos of public service and their implementation of the principle of public provision of healthcare for all, free of the distortions of market and profit, is as relevant today as it has ever been.

Sources:

The Save Finsbury Health Centre blog is a vital source for this article and for anyone concerned for the future of the Centre. There are many webpages focusing on the Modernist architectural heritage of the Centre; the best is in BD Online.

And I used it regularly when my daughter was small (I think for feet and teeth?) – always got a lift.

A friend of mine got her feet done there today this very day.

PS as in a lift of the spirits!

Pingback: The Spa Green Estate, Finsbury: ‘an outstanding advance in municipal housing…one of the showpieces of London’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Woolwich’s Interwar Health Centres: ‘monuments to man’s achievement and to his folly’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Local government…the first-line defence thrown up by the community against our common enemies’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Walworth Clinic, Southwark: ‘the Health of the People is the Highest Law’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Walworth Clinic, Southwark: ‘the Health of the People is the Highest Law’ - Socialist Health Association

Pingback: Open House London 2016: A Tour of the Capital’s Council Housing, Part Two | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Open House London 2016: Town Halls – Civic Pride and Service | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: A Radical Riverscape: Architecture and Revolution down the Fleet | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Open House London, 2017: A Tour of the Capital’s Council Housing | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Open House London, 2018: A Tour of the Capital’s Council Housing | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: The Spa Green Estate, Finsbury: ‘an outstanding advance in municipal housing…one of the showpieces of London’ | Municipal Dreams

Pingback: Housing Ordinary People in London, by Jane McChrystal. – londongrip.co.uk