Tags

Michael Romyn, London’s Aylesbury Estate: An Oral History of the Concrete Jungle (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020)

The estate was like a shiny new penny. It was lovely. It was really lovely. It’s hard for me to paint a picture for you but it was a beautiful place to live … The community side of it, you know? I mean you knew all the neighbours … You know you would never have got that sort of community in a row of houses as you did with the landings …

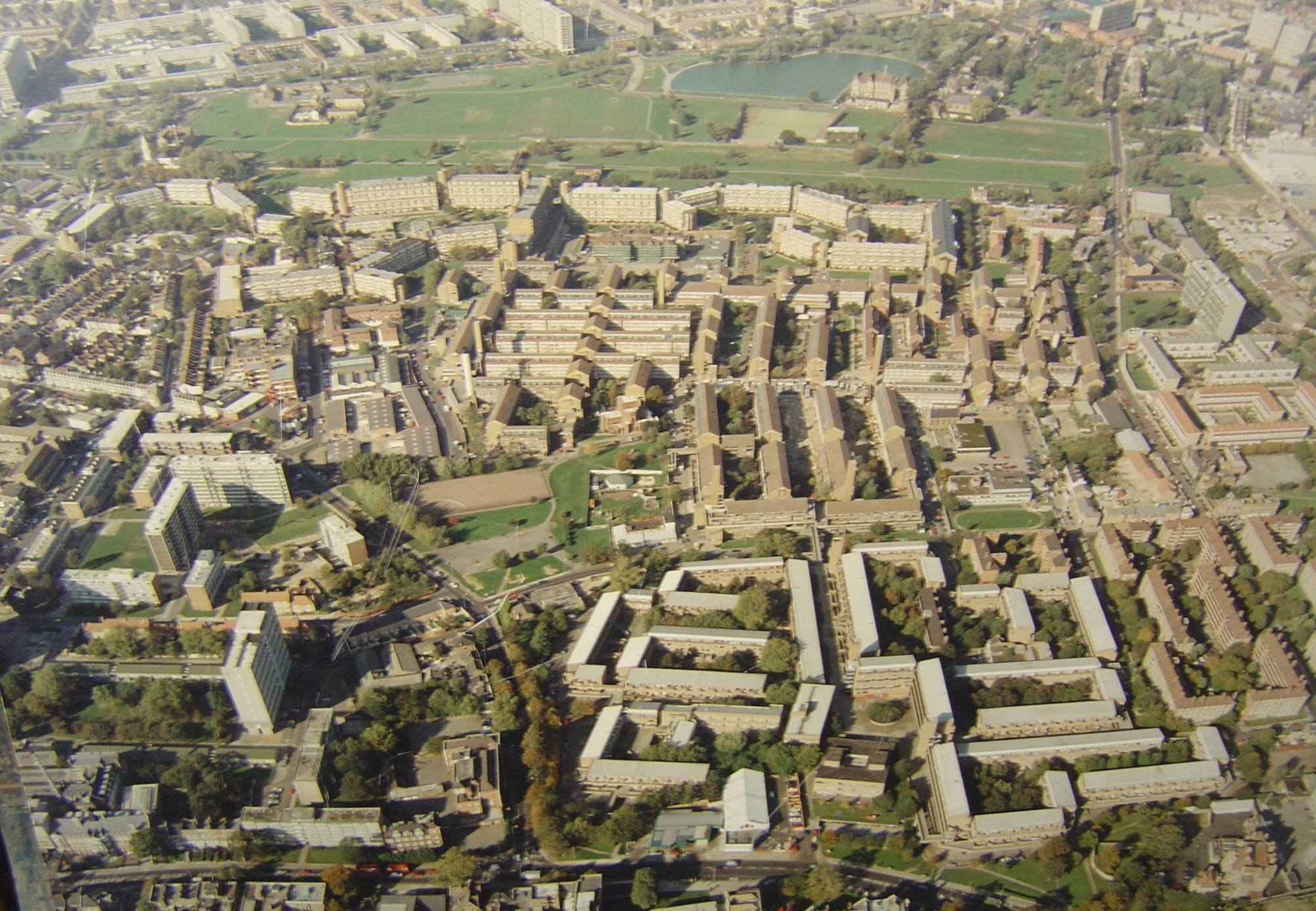

Robert Banks is talking about Southwark’s Aylesbury Estate. For many readers, his words might come as a shock and, to be honest, I’m tempted just to leave it there as a simple corrective to the unreasoned obloquy that the estate has suffered. As Michael Romyn writes in the introduction to his essential new book, ‘a reputation is usually earned; in the Aylesbury’s case it was born’. Even on the day of its official opening by Anthony Greenwood, Labour’s Minister of Housing and Planning in October 1970, it was described by one local Tory councillor as a ‘concrete jungle … not fit for people to live in’. That might have come as a shock to the new tenants who felt ‘it was like moving into a palace’.

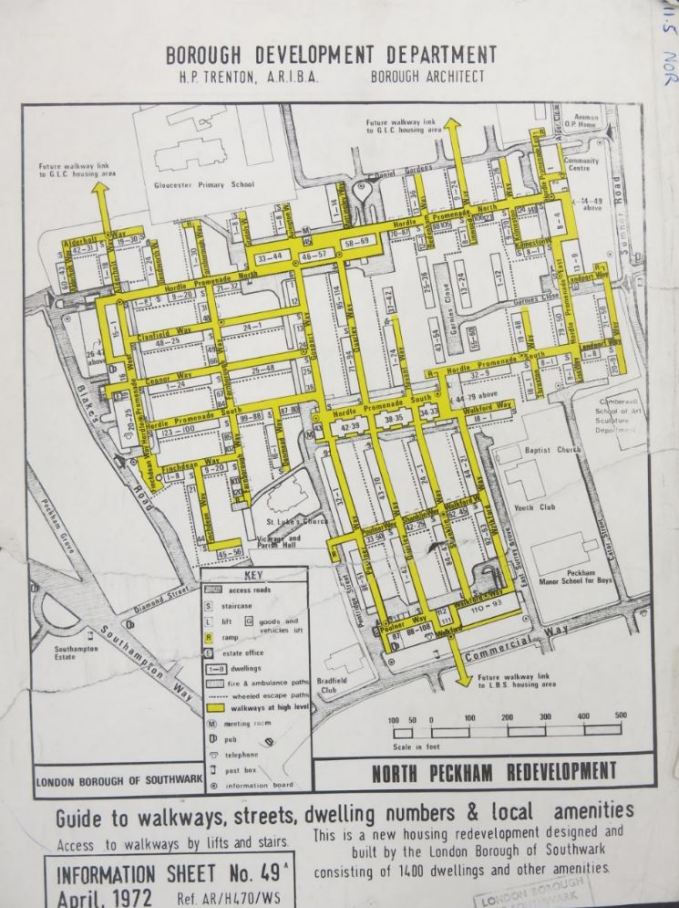

The estate was born in the laudable post-war ambition to clear the slums and in the 1960s’ fashion for large-scale, modernist solutions to housing need. It comprised 2700 homes in all, housing a population of almost 10,000 at peak, in 16 four- to fourteen-storey so-called ‘snake blocks’ (including what was allegedly the largest single housing block in Europe). Designed by Southwark Council’s Department of Architecture and Planning, it was built by Laing using the Jespersen large panel system of prefabricated construction. The estate’s regeneration – in practice, its demolition and replacement – has been planned since 1998.

Romyn’s book offers essentially another form of deconstruction, not of the estate itself, but of the myths and meanings that have become attached to it. Robert Banks provides one of the 31 past and present residents’ testimonies that lie at the heart of this thoroughly researched book. That residents’ voice shouldn’t be an unusual means of understanding the actual lived experience of council tenants – who find themselves and their homes so frequently misrepresented and maligned in the media and wider commentary – but, sadly, it is. In the case of the Aylesbury, it is all the more vital as no estate has been so unfairly vilified.

We should begin, I suppose, with that ‘reputation’: the estate portrayed as a ‘concrete jungle’ (indeed, almost its archetype), a scene of crime and disorder. Romyn quotes Sir Kenneth Newman, Metropolitan Police Commissioner, who in 1983 described London’s council estates more generally as ‘symbolic locations’ where:

unemployed youths – often black youths – congregate; where the sale and purchase of drugs, the exchange of stolen property and illegal drinking and gaming is not unknown … they equate closely to the criminal rookeries of Dickensian London.

We’ll leave aside for the moment the unconscious (?) racism of his comment and note its surprisingly conscious myth-making: estates, such as the Aylesbury, were imagined rather than analysed, just as, in fact, Victorian elites fearfully mythologised the slum quarters of their own large cities. (1)

As Romyn writes:

Simplified, fetishized, objectified, and finally commodified, council estates rendered in this way, were imaginary constructs, their meaning defined not by their histories or inhabitants, but by external agencies of control (politicians, police, the media, etc).

Newman avoided the word ‘gangs’ but Romyn reminds us how readily the stigmatising term was applied to very largely innocuous groups of young people, particularly those of colour, simply hanging out on their home turf. That so many of the estate’s population were young – in 1971, 37 percent of its 9000 population was under 16 – was, as he notes, an objective factor in such problems as did exist.

If this sounds dismissive of those problems, it should be said that Romyn is scrupulous in assessing the evidence. He notes, for example, that in 1999 around 40 percent of estate residents expressed fears for their personal safety. It’s a disturbing figure but it was roughly in line with the proportions in Southwark and London more widely.

Romyn contends that what really marked the estate out was:

its physical attributes – the brawny slabs … the circuitous geography of elevated walkways. Immediately expressive of the ‘gritty’ inner city, the estate distilled many of the fears and fantasies of urban life embedded in the popular imagination.

These, of course, were also grist to the mill of the ‘Defensible Space’ theorists who posited that elements of ‘design disadvantage’ – the illegibility of public/private space, multi-storey accommodation, shared entranceways and those walkways – were the cause of crime and antisocial behaviour. These, I hope, largely discredited ideas had become by the 1990s the ‘common sense’ of planners and politicians alike and featured heavily in the writings of the media commentariat.

But while lurid headlines and alarmist reports filled column inches, actual crime rates on the estate and the incidence of anti-social behaviour were similar to those of surrounding areas; the estate wasn’t an idyll (though many growing up in the era remember it fondly) but it was essentially normal. Romyn quotes Susan Smith who has suggested ‘fear of crime may be better seen as an articulation of inequality and powerlessness so often experienced as part of urban life. So too can it mask deeper anxieties about changes to the social order …’. Media representations of, as one report labelled it, this ‘concrete den of crime’ were, as Romyn argues, ‘wildly disproportionate, and wanton, too, in that they stoked and projected an unearned notoriety’. (2)

Moving to the question of ‘community’, a leitmotif of planning since 1945, Aylesbury might again surprise those who have criticised it so freely. Romyn charts, particularly in the estate’s early years, a neighbourliness and localism centred around the East Street market and nearby pubs and shops – in fact, a connectedness with the neighbourhood in direct contradiction to conventional wisdom surrounding estates and their supposed isolation. An active tenants’ association, a range of community activities, informal cleaning rotas of common areas and so on complete the picture.

Changing demographics could fray this community cohesion. The arrival of larger numbers of ‘problem families’ – at times described as ‘rough’ by more established residents – under homelessness legislation sometimes led to tensions and difficulties. But Romyn reminds us, again with personal testimony, how life-changing for the families themselves this move could be. Linda Smith, who moved to the estate with her two young children in 1990 via a women’s refuge and bed and breakfast accommodation, recalls how, ‘in [her] time of need along came Southwark’. I don’t need to say how necessary it is that these services are properly funded and resourced and how vital social housing is to that.

Race became another complicating factor for this initially very largely ‘white’ estate as black and minority residents moved in. But this necessary transition seems to have been negotiated well for the most part; the tenants association remained fairly old school but new grassroots community organisations emerged and made a vital contribution to Aylesbury’s life and vitality.

All this in an era of real and growing hardship. The data is profuse. As traditional employment declined and joblessness rose, by 1975 the average household income in Southwark was £1000 below the UK mean; by 1985, half its households were on Housing Benefit. By the late 1990s, Faraday Ward (largely comprising the estate) was the third most deprived ward in Southwark and among the fifth most deprived in England; half its children were on free school meals (compared to 16 percent nationally).

This wasn’t the time to cut public spending and services but the relentless Thatcherite urge to ‘balance the budget’ imposed swingeing central government cuts to housing grants and allocations. On the Aylesbury (as elsewhere), routine maintenance was cut and internal redecoration halted; caretakers were reduced and then removed completely in 1990; cleaning staff were reduced and then lost to Compulsory Competitive Tendering in 1991.

The real quality of Romyn’s book, however, is that it is not a polemic (and is all the more plausible for that). He acknowledges the inefficiencies of some of the Council’s services, its Direct Labour organisation, for example. He recognises the improvements achieved through new, more devolved forms of housing management. But the sense of an estate not failing but failed by others is palpable.

For all that, when in 1999 Southwark Council commissioned a ‘mutual aid’ survey of the estate, it found that 90 percent of residents knew and helped neighbours; 20 percent were helped by a relative living on estate and 35 percent had friends and relatives living nearby. This suggests a resilience and community challenging the dystopian stereotypes repeated most famously by Tony Blair in his first public speech after New Labour’s landslide victory in 1997 on the estate itself.

We might, nevertheless, see the £56.2m awarded to the Aylesbury two years later as part of a New Deal for Communities regeneration package as an attempt to right past wrongs. In practice, it was for most residents a poisoned chalice which threatened established and generally well-liked homes and it came cloaked in a moralising language that insulted them and their community. This ‘moral underclass discourse’:

pointed to imputed deficiencies in the values and behaviour of those who were supposedly excluded – ‘an underclass of people cut off from society’s’ mainstream, without any sense of shared purpose’ according to Blair.

The apparently benign goal of ‘mixed and sustainable communities’ was expressed more crudely by Southwark’s Director of Regeneration, the suitably villainously-named Fred Manson:

We need a wider range of people living in the borough … [council housing] generates people on low incomes coming in and that leads to poor school performances, middle-class people stay away.

We’re trying to move people from a benefit-dependency culture to an enterprise culture. If you have 25 to 30 percent of the population in need, things can still work reasonably well. But above 30, it becomes pathological.

Local Labour politicians might, one hopes, have known better but the motion of censure for this intemperate and abusive language came from Tory councillors. The residents’ own response came in December 2001 when, in a 76 percent turnout, they voted by 73 percent to reject the transfer of their homes to the Faraday Housing Association (formed for the purpose) which would oversee the regeneration process. Fears of increased rents, reduced security of tenure, smaller homes and gentrification all played their part.

Since then, regeneration has rumbled on. It has had some beneficial effects. Increased spending and support for education, for example, increased the proportion of local students gaining five GCSEs at Grade C or above from a shocking 16 percent in 1999 to 68 percent – just below the national average – in 2008. That this was achieved before any part of the estate was demolished testifies to the benefits of direct public investment and the fallacy that clearance was required.

A small part of the estate was demolished in 2010, existing blocks replaced as is the fashion with mixed tenure homes in a more traditional streetscape. Most of the estate remains though it and its community have been scarred by the interminable process and continued threat of regeneration.

Whilst thoroughly readable, London’s Aylesbury Estate is an academic book – with an excellent apparatus of references and bibliographies – and it comes unfortunately at a hefty academic price. For anyone concerned to truly understand the estate and its history, however, I recommend it as the definitive text.

I’ll conclude with some conclusions that I think apply not only to the Aylesbury but to estates more generally. The first is that we should eschew simplifications and embrace complexity. Actual residents, for the most part, experienced the estate very differently from its media portrayals. Many didn’t even experience it as an ‘estate’ at all – they knew their corner of it and generally got on with their immediate neighbours. Some were fearful of crime and an unfortunate few experienced it but another interviewee recalls that he ‘didn’t come across anything anti-social in all [his] time there’. Many remember – and continue to experience – neighbourliness; conversely, some rather liked the anonymity the estate could offer.

Secondly, we must reject the idea of estates as alien. As Romyn argues:

Council estates are just homes after all. For most residents, they are not media props or architectural crimes or political rationales, but places of family, tradition, ritual and refuge …

Let’s allow the Aylesbury Estate to be simply – and positively – ordinary:

For all that was exceptional about the estate, and for all the mystification it endured, the Aylesbury, in the eyes of its residents, was mostly normal, unremarkable; a place of routine and refuge, of rest and recreation, of family and familiarity.

Thirdly, we might wish those residents for once to be not the object of other people’s stories but the subject of their own.

Publication and purchase details can be found on the publisher’s website.

Notes

I’m grateful for permission to use the images above which are drawn from the book.

(1) This is argued by Dominic Severs in ‘Rookeries and No-Go Estates: St Giles and Broadwater Farm, or middle-class fear of “non-street” housing’, Journal of Architecture, vol 15, no 4, August 2010

(2) The reference here is Susan J Smith, ‘Social Relations, neighbourhood structure and the fear of crime in Britain’ in David Evans and David Herbert (eds), The Geography of Crime (Routledge, 1989)

I wrote about the Aylesbury Estate myself in two blog posts back in 2014. I’d revise some of my language and analysis back then in the light of my own further research and certainly with the benefit of Michael Romyn’s book but they might still serve as a useful guide to the overall history.

That, of course, was hardly a ringing endorsement and the truth of crime, and fear of crime, was real enough. Back in 1987 again, the police had recorded 70 muggings across the Five Estates area in one week. (5) The reality of crime, in its starkest form, became evident in November 2000 with the death of Damiola Taylor, a ten-year old Nigerian schoolboy whose family had recently moved to the UK – killed in an isolated stairwell of the North Peckham Estate.

That, of course, was hardly a ringing endorsement and the truth of crime, and fear of crime, was real enough. Back in 1987 again, the police had recorded 70 muggings across the Five Estates area in one week. (5) The reality of crime, in its starkest form, became evident in November 2000 with the death of Damiola Taylor, a ten-year old Nigerian schoolboy whose family had recently moved to the UK – killed in an isolated stairwell of the North Peckham Estate. The death occurred as the estate’s regeneration was already underway but it seemed to confirm the worst fears and strongest criticisms of those who blamed the estate’s design for its troubles.

The death occurred as the estate’s regeneration was already underway but it seemed to confirm the worst fears and strongest criticisms of those who blamed the estate’s design for its troubles.