Tags

Last week, we introduced you to the architectural vision of Ted Hollamby and the reforming ideals of a generation of Lambeth councillors. They came together in Cressingham Gardens – a council estate intended to provide a sense of community and the highest quality housing for the ordinary people of the Borough. That legacy is now under threat.

Cressingham’s neighbourliness was fostered by a number of small design touches – front doors which faced each other, kitchen windows facing the walkways outside, and the walkways themselves which separated people and cars.

The estate as a whole was designed as a mixed community with homes suitable to elderly and disabled people, single people and couples as well as families. A nursery school was provided in the innovatively-designed building now known as the Rotunda.

It was a ‘green’ estate also. Many of the larger homes have patio gardens – a Hollamby signature at this time. All were designed to overlook green open space. Even in the centre of the estate, existing trees were preserved or new ones planted. Concrete flowerbeds were provided on the raised walkways to ensure every home its splash of greenery and colour.

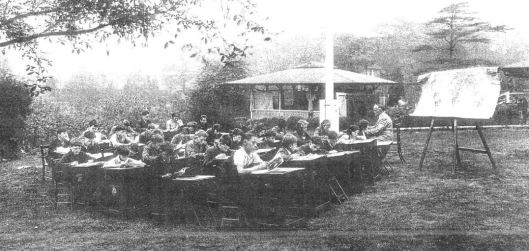

This panoramic view shows Teletubby Land with the estate nestling behind to the left and the near seamless border with Brockwell Park to the right. Click for a larger image.

But the most striking aspect of the estate is its location at the edge of Brockwell Park. In the dry language of the architects’ design brochure: (1)

It is proposed to provide all the accommodation needed in low rise dwellings. This will avoid any visual obtrusion on the views from Brockwell Park and will ensure that all dwellings will have a close contact with the site. Part of the plateau has been kept clear of buildings to extend the landscape of the Park into the site. The buildings are arranged around this in such a way that the lower buildings are adjacent to it with the height increasing to a maximum of four storeys around the perimeter of the site away from the park.

Real life, in this case, exceeds architectural description. From the park, the estate is an almost seamless addition to its horizon; from the estate, the park seems almost to be its back garden. They blend literally in what residents call Teletubby Land for its three green mounds – a central green space which is part of the Brockwell Park Conservation Area.

This was a hard-fought achievement. In presenting the scheme, its lead architect, Charles Attwood argued successfully for a density of 100 persons per acre (against the expected 140) and he used a contour map of the site to identify ‘sightlines’ from the park by which to place the ‘fingers’ of low-rise development. Higher density housing in linked blocks was used to create a perimeter which sheltered the rest of the estate from the noise of Tulse Hill Road.

The council minutes of the committee meeting which approved the design were unusually expressive in recording the councillors’ congratulations to Cressingham’s architects on their ‘bold and imaginative scheme’. (2)

Equal care was taken in the design of the individual homes. Parker Morris standards guaranteed spacious homes but Hollamby and his team ensured they were as light and airy as possible with internal walls minimised, floor to ceiling windows provided which overlooked green space, high ceilings and skylights.

Equal care was taken in the design of the individual homes. Parker Morris standards guaranteed spacious homes but Hollamby and his team ensured they were as light and airy as possible with internal walls minimised, floor to ceiling windows provided which overlooked green space, high ceilings and skylights.

According to Ken Livingstone, Hollamby ‘passionately believed that council housing should be as good if not better than private housing’. (3) In Cressingham Gardens he triumphantly achieved this.

In all, 290 homes were planned. A small extension to the scheme at its northern perimeter raised this to 306. Construction began on the £1.58m contract in May 1971 with an estimated completion date of January 1974. In those turbulent times within the building trade, by the summer of 1972 the contractors were already over six months behind schedule and in October work was halted by a national building strike. The job was finished by direct labour and eventually completed in 1978.

In all, 290 homes were planned. A small extension to the scheme at its northern perimeter raised this to 306. Construction began on the £1.58m contract in May 1971 with an estimated completion date of January 1974. In those turbulent times within the building trade, by the summer of 1972 the contractors were already over six months behind schedule and in October work was halted by a national building strike. The job was finished by direct labour and eventually completed in 1978.

And that, in a sense, should be the end of the story. The estate has been a good home to generations of residents – as they’ll tell you themselves: (4)

When we came here, we thought ‘my God! It’s wonderful!’

It was like a fairy-tale, so beautiful

Of the 300 homes currently occupied, almost 70 per cent are still rented from the Council (or Lambeth Living in its current incarnation). While there have been problems of crime and anti-social behaviour in the past, Cressingham now ‘is seen as a safe place’ and its crime rate is lower than surrounding areas.

Overwhelmingly, residents talk of their friendly neighbours and the estate’s strong sense of community – they look out for each other, keep an eye on each other’s children. It’s what planners call ‘natural surveillance’ nowadays. It’s really just part of that ‘village-like’ feel that Hollamby hearkened to all those years ago.

This is then by all accounts a success story except for the fact that the estate has, like the rest of us, grown older. Six flats at the northern end of the estate have been empty for sixteen years due to subsidence. It’s stated that repairs would cost £260,000 – a relatively small amount given the overall shortage of social housing and some question why the Council has allowed these flats to remain empty for so long.

A 2013 Council survey claimed that 40 per cent of council homes did not meet the current Decent Homes standard. The estate’s supporters query the figure which appears to result from a more general stock review carried out in 2012.

Structural surveyors, commissioned to carry out an estate-wide survey which might achieve ‘a common understanding, concluded that the structural condition of the homes was ‘generally acceptable’ though localised areas did ‘warrant repair’. It’s obvious that failing zinc roofs and guttering require replacement but the report also makes it clear that many non-structural and drainage problems have been caused by poor tree maintenance over the years. (5)

Lambeth has claimed it will cost £3.4m to carry out such works. It has also, in the meantime, raised the spectre of regeneration. (6)

Residents of other London estates – such as the Aylesbury Estate in Southwark and Woodberry Down in Hackney – understand the potential implications of such plans well. Higher density housing, new registered social housing landlords and increased rents, the loss of social housing units (homes to the people who need them), ‘affordable’ rents which are a travesty of the term, and a sell-off of prime real estate to private developers have all been central elements of the regeneration schemes implemented to date.

Currently, the Council claims a range of options are still on the table, including refurbishment only, infill, various partial redevelopments and comprehensive redevelopment. (7) Faced with resident protest, it has begun what appears to be a more authentic process of consultation though those most fearful of the regeneration option question its sincerity. Many residents also question why the estate has been so poorly maintained over many years and fear a hidden agenda. A number of estates subject to ‘regeneration’ have been run down until demolition was claimed as the only viable option.

The bottom line is that the majority of Cressingham’s residents love their estate and want to stay in it as it is. An independent survey (carried out by Social Life commissioned by the Council to lead on resident engagement) found 81 per cent wanted to stay in their homes with repairs done. The ten per cent who wanted to move either wanted bigger homes or were fearful of the disruption of redevelopment. That is effectively a unanimous vote in favour of the Estate – a massive tribute to the vision and professionalism of Ted Hollamby and his team and the Lambeth Council of earlier years.

In 1974, Hollamby outlined a philosophy of architecture that was ‘anti-monumental, anti-stylistic, and fit for ordinary people’. In 1981 Lord Esher, past president of RIBA, described Cressingham Gardens as ‘warm and informal…one of the nicest small schemes in England’. That might sound rather faint praise in a different context but it’s surely exactly the kind of encomium that Hollamby would have wished for and it’s one whose truth the estate’s residents would surely endorse. (8)

If you’re in London, do visit the estate during the Open House London weekend on 20 and 21 September, 2014. For more information on the residents’ campaign against regeneration and background on the estate, visit Save Cressingham Gardens.

Sources

(1) This – with a range of other resources and thorough description and analysis – can be read at the excellent post by Single Aspect on Cressingham Gardens.

(2) Lambeth Borough Council Housing Committee minutes: 20 January 1969 (LBL/22/6)

(3) Ken Livingstone, You Can’t Say That: Memoirs (2011)

(4) Social Life, Living on Cressingham Gardens: Social Life’s conversations with residents 20.10.13

(5) Tall Consulting Structural Engineers, Cressingham Gardens Estate SW2 Structural Report, November 2013

(6) Cressingham Gardens: Lambeth Housing Standard cost assumptions

(7) Karthaus Design Ltd, Cressingham Gardens Outline Redevelopment Options Study (June 2014)

(8) The Hollamby quote is from ‘The Social Art’, RIBA Journal, March 1974; the Esher quote can be found in A Broken Wave: the Rebuilding of England, 1940-1980 (1981)

The Save Cressingham Gardens campaign has created a fine video on the estate and its residents available here on YouTube.

For more information, description and illustration of the estate, do visit the blog post by Single Aspect.