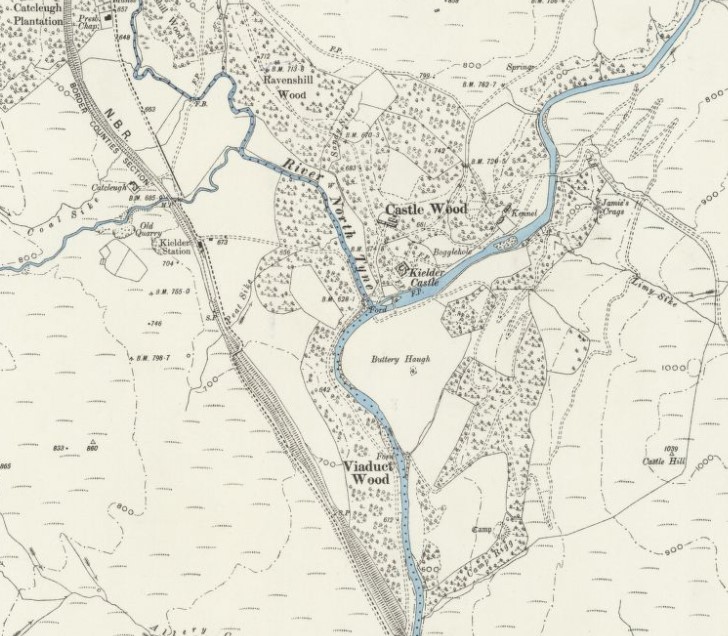

Kielder in Northumberland, population 194, is by most accounts the most remote village in England. The nearest cash machine is 18 miles away in Bellingham and the nearest shopping centre, Hexham, is a 53-minute drive – there are no public transport options. On the other hand, residents enjoy a deeply rural location and the 580 square miles of star-lit sky known as the Northumberland International Dark Sky Park.

To some of us, its history and design will be of even greater interest – the village provides a small blueprint of the ideals of one of Britain’s most influential planners, Thomas Sharp, and a cameo of the forces and dynamics that shaped the wider nation in the twentieth century after two world wars.

In the nineteenth century, the area seemed, in British terms, a wilderness – predominantly open moorland with some low-intensity sheep grazing – but one that provided excellent sport for the local landowner, the Duke of Northumberland. His shooting box – a misleadingly modest term for the rather large mock-Gothic castle built in 1775 – was located in Kielder.

And, then, somewhat surprisingly but reflecting the ambition and competition of the age, Kielder acquired a railway station in 1862 when the Border Counties Railway drove a line up the North Tyne Valley from Hexham to join the Scottish rail network at Riccarton Junction.

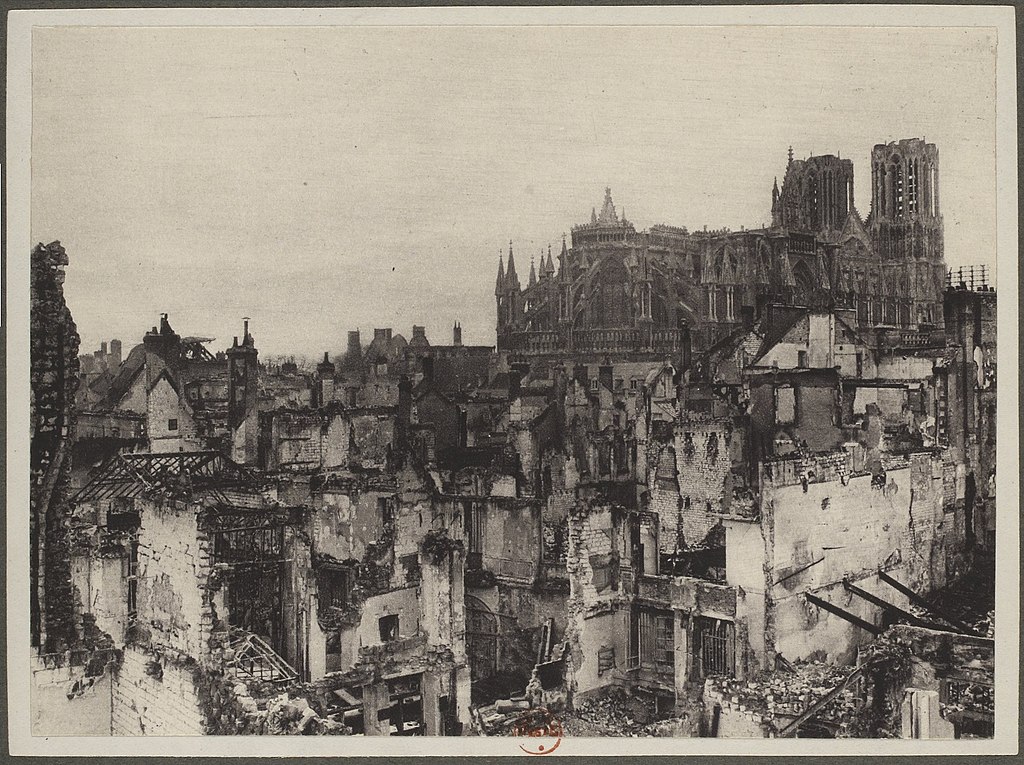

The First World War had a greater impact. By the turn of the century, forests and woodland accounted for just four percent of Britain’s land surface. As a trading nation, we’d been happy to import most of our timber but the threat of blockade and the needs of total war concentrated minds. In July 1916, Sir Francis Acland was asked ‘to consider and report upon the best means of conserving and developing the woodland resources of the United Kingdom’. The 1919 Forestry Act that established the Forestry Commission with powers to acquire and plant land and promote timber supply and forest industries was the result.

The Commission bought its first land at Kielder from the Duke of Northumberland in 1925. The death of the eighth duke in 1930 and incumbent death duties forced the sale two years later of a further 47,000 acres (over 19,000 hectares). The initial planting of what became, at 235 square miles, England’s largest forest proceeded over the next ten to fifteen years. Some early commentators were critical of the Commission’s plans: (1)

whole sections of the country are being turned into tree slums – places where overcrowding is taking place without imaginative design – thus creating ugly landscapes.

Its decision to consult the Council for the Preservation of Rural England was deemed too little, too late. Such criticisms were to persist, of course. The coniferous Sitka spruce, an import from North America, covers about 75 percent of the planted area of Kielder Forest.

The first Forestry Commission housing at Kielder was built from 1935 – pebble-dashed and painted semi-detached and terraced homes in Castle Drive (next to the station) which wouldn’t have looked out of place in a pleasant garden suburb. Most houses remained scattered through the forest where they were needed for the early detection of fires and rapid fire-fighting.

These were certainly superior conditions to those enjoyed by the unemployed men of the north-east who, desiring to ‘avail themselves of the opportunity for training and reconditioning’, found themselves placed in summer camps in Kielder. By the mid-30s, 200-250 men were accommodated in a camp of temporary hutments in Kielder, others were dispersed under canvas. This was part of the Ministry of Labour’s policy towards the so-called ‘distressed areas’, four areas suffering particularly high unemployment during the Great Depression; Tyneside was one (the others being South Wales, Cumberland and central Scotland). The Ministry was at pains to emphasise that the Government was not engaged in the business of job creation; ‘the men will receive a small allowance, unemployment pay being set off against the costs of their maintenance’. (2)

In the event, a second world war provided employment for Britain’s jobless. It also strengthened the economic case for the development of Kielder Forest; a case made all the sharper by the balance of payments crisis that hit the country in 1947. At the same time, the hopes and expectations engendered by wartime struggle and eventual victory brought new ideals as to how the British working class and Kielder’s workers should be treated.

The economic arguments were well captured in a local press article headlined ‘Northumberland Forest Will Save Dollars’ as it described how the Forestry Commission’s plans for Kielder: (3)

should save us 46 million dollars-worth of timber exports in the next twenty years. It should also give employment to 2,000 lumberjacks as well as thousands more engaged in the timber industry.

It was a sign of the times that of the 350-strong workforce currently employed, some 60 to 70 were workers transferred voluntarily from displaced persons camps in Europe.

Something far better, however, was planned for the future. To some, thoroughly briefed by the Commission, trees were ‘the Harbingers of a Rural Revolution’. Eight new villages were planned for the Forest, Kielder itself would be the largest – ‘new village communities of estate workers, adequately and compactly housed, and enjoying a high standard of local amenities’. Nowadays we might question the enthusiasm of the reporter but, at a time of genuine belief in a better future, perhaps he or she was right to conclude:

There can be no doubt that Britain’s new efforts will enrich the countryside physically, economically and socially. Those who are carrying out the policy are not merely silvicultural experts but men of imagination, fired with the ideal of balanced, prosperous and happy rural communities.

Thomas Sharp, one of the foremost town planners of the day, was the person appointed by the Forestry Commission in 1946 to implement this vision. Sharp had been born to a working-class family in County Durham. Apprenticed to a surveyor, he made his name as a town planner with his first book Town and Countryside, published in 1932, and, in 1940, Town Planning, a Pelican paperback that sold 250,000 copies. During the war, he was seconded to the Ministry of Works and Buildings as Secretary to the Scott Committee on Land Utilisation in Rural Areas.

Sharp was the principal drafter of its 1943 Report and among its recommendations – tellingly for his future work – was the following: (5)

New villages and extensions of villages should be planned, and should as far as possible be of a compact and closely knit character: no attempt should be made to recreate in new villages the irregularity and ‘quaintness’ of old ones.

The Report also suggested that terraced housing made for the best form of village housing.

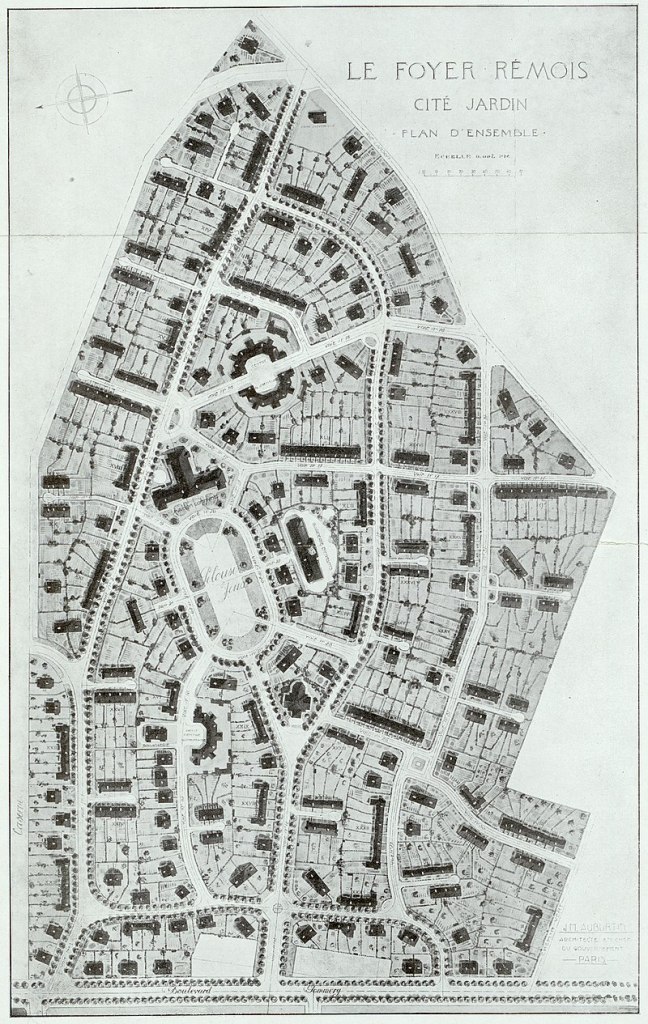

In 1946, Sharp published Anatomy of the Village in which he identified five historic village types (reflecting differing patterns of development) but concluded that most villages, especially in the north of England, were nucleated, that is built around a distinct centre. This became his personal preference.

At the same time and as he looked to the future, he eschewed pastoral nostalgia:

The rural feeling of the village does not depend on any of those things that are popularly associated with it, flowering gardens, irregular, informal, and quaint buildings, and so on. It seems to depend on much smaller and more subtle things, upon a certain modesty, a certain lack of the smooth, mechanical finish of the town, and above all upon the harmony of the material of its buildings with the countryside.

This allowed him to advocate planning and, in effect, what John Pendlebury has called an ‘a kind-of ordered informality’. Sharp wrote in Anatomy that:

The new villages … should be clean straightforward streets of honest modern buildings, grouped in a square or a series of squares or similar formations, round a simple green or gravelled space where maybe the telephone box may take the place of the village pump.

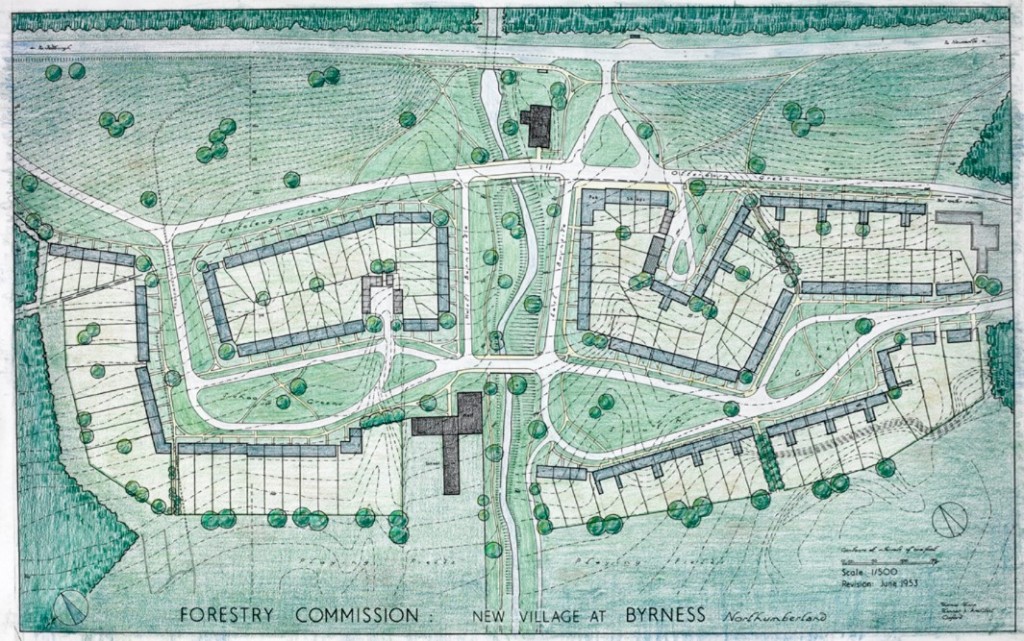

In all this, Sharp seemed the perfect person to design the eight new villages proposed by the Forestry Commission. As Sharp himself wrote, the intention was that ‘every village shall be of a size to be able to provide a reasonably satisfactory social life of its own, and shall be sufficiently large to support a primary school and other necessary village institutions’. Six of the eight were to have a population of 350 or less but Kielder (and one other) was planned to contain 220 houses accommodating around 800 people. (6)

Sharp acknowledged the objections that the new settlements would be little more than ‘“company villages” and may develop the unpleasant characteristics that such villages had in the past’ but he was confident that:

with the strong trades unionism of to-day that would be nearly impossible, even if (an extremely unlikely event) a public body such as the Forestry Commission did tend to develop the characteristics of nineteenth-century captains of industry.

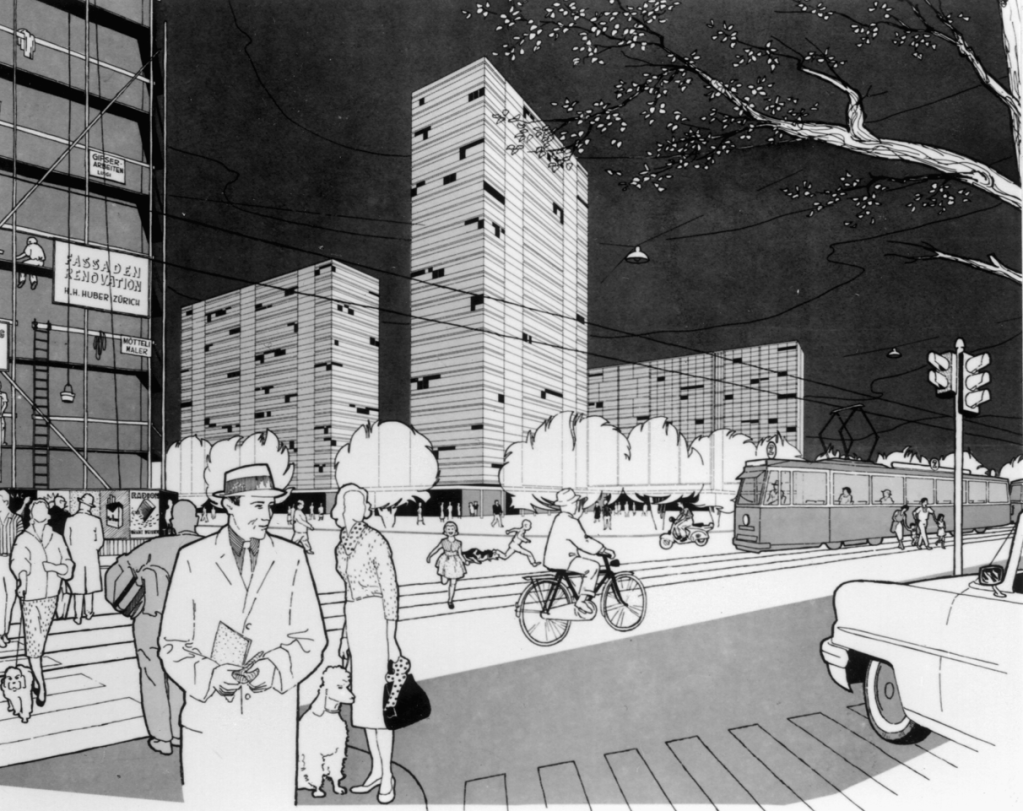

As construction began in the early to mid-1950s, Sharp returned to his key themes: (7)

In designing the lay-out plans, the aim has been to try to capture for each place the character of a true village as distinct from a mere housing estate or a bit of suburbia dropped down miles away from a town. Each village will have a central square or place and most of the houses will face on to enclosed greens that will be given freely-designed forms, as distinct from either deliberately-created formality or carefully-calculated informality.

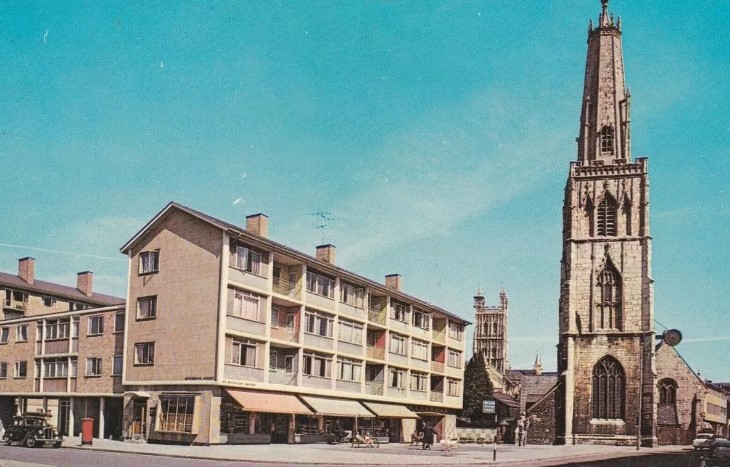

He reiterated his support for terraced houses ‘because they will contribute more to village character that way and because they will thus gain mutual snugness against the weather of the exposed region’. [It’s interesting to note that Tayler and Green, in the superb range of council they designed for South Loddon Rural District Council from the late 1940s, also advocated terraced housing for its ‘advantages of economy, warmth and restful appearance in the landscape’. (8)]

But there was to be no attempt to ‘make them traditional in appearance’. The local dark stone was unsuited to contemporary construction and to the appearance of new villages set amidst dark coniferous forest. Colour-washed housing ensured ‘the villages will not only be light-looking in themselves, they will also enliven the far-stretching monotones of the forests’. (9)

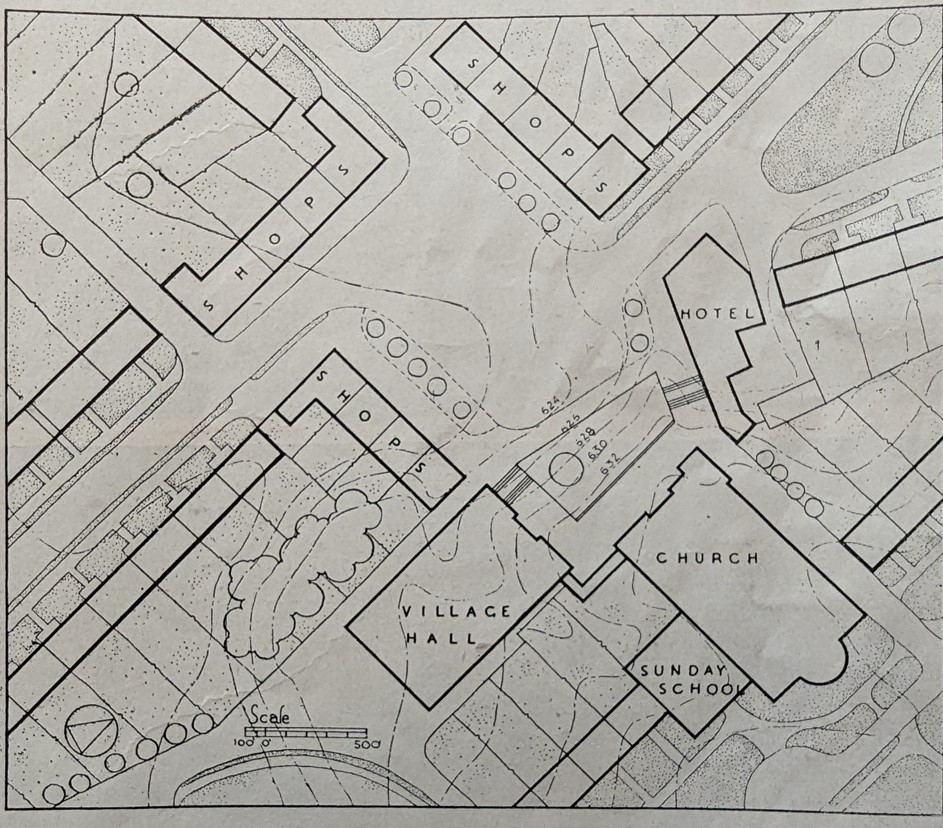

At Kielder itself, Sharp resisted ideas that the bulk of the new village should be built as an extension of the existing housing centred on Castle Drive. Instead, he favoured a new site at Butteryhaugh about 500 metres to the south-east. (Technically, it might be considered a separate village but is generally treated as part of Kielder Village.) The 1949 article in Architect & Building News outlined his ambitions. (10)

The layout has been designed to secure good village character. Since this village will act as a kind of local capital, a fairly substantial village centre has been planned to contain a dozen shops, a couple of pubs, as well as the church and a village hall where films can be shown once or twice a week.

In May 1952, Kielder village was officially opened by the chairman of the Forestry Commission, Roy Robinson, officially ennobled in 1947 as Lord Robinson of Kielder Forest. As the village developed, Sharp was disappointed that it was the Ministry of Works, rather than the Forestry Commission, that oversaw the housebuilding and disliked its bureaucratic insistence that all roads should have standard concrete curbs. He was happy, however, with the houses themselves (designed by Robert Mauchlen of the respected Newcastle architectural practice, Mauchlen & Weightman) which did at least conform closely to the principles he had set out.

In time, Sharp’s frustrations with the Forestry Commission itself grew. He was angry at their refusal to build and support the community infrastructure – the pubs, clubs and shops – that were integral to his vision. He resented the fact, irony of ironies, that the Commission, after much pressure, only provided £5 or so per village to support amenity tree planting. He resigned his post and later declared Commission ‘the worst client he had’. (In fairness, Sharp had somewhat of a record of falling out with those who employed him.) (11)

Even some of the new residents annoyed him:

some of the tenants have demanded the right to dig up the village greens for rose gardens and flower and vegetable patches, and have brought in the local M.P. to support them in their fight against the tyranny of planners.

That local MP, Rupert Speir, whose Hexham constituency took in Kielder, emerged as one of the fiercest critics of the Forestry Commission’s performance in the Kielder villages. In 1954, Speir complained in parliament that they lacked ‘a shop, a club, a “pub,” a hall, a telephone kiosk or a stamp machine. I believe that there is not even a letter box’. He was similarly critical of the housing at Kielder: ‘It would be hard to imagine anything more like a dockyard settlement, or anything more grey and forbidding’. The last straw for the Forestry Commission workers, paid the minimum agricultural wage but paying full rent and rates (80 pence and 20p respectively weekly) but receiving minimal services was that the Commission required them to pay full price for their Christmas trees cut from the approximately 120 million in the forest. (13)

Some of this was unfair, as the junior minister responding pointed out, given that the villages were so new but Speir returned, equally caustically, to the fray six years later: (14)

at Kielder, there are … well over 100 houses, with a population of 400, and yet there is not one single general shop in that village. The nearest shops are miles away. There is no inn, and the village hall is nothing more than a tin shack.

And he still thought – he repeated the phrase – that the new houses looked ‘like nothing more than a dockyard settlement’. The Conservative MP felt that, if Commission employees had withdrawn their labour, ‘a strike would have been fully justified’.

Others, looking back, were also critical – or at least very aware – of the power of the Commission: (15)

It was a Forestry Commission village, and forestry ruled the roost and everything was done to their beck and call … it was their land, it was their houses, it was their road, it wasn’t council run roads, it belonged to the Forestry Commission … they cleaned the streets, snow and what have you … they owned the houses, they owned all business, the little shop, … the little café, they owned all the books, … all revolved around the Forestry Commission.

If it wasn’t, negatively, a company town, it was certainly what the sociologists would call an occupational community.

Nowadays, in contrast to Speir, I think most observers would agree now that the village’s homes are attractive in just the ways that Sharp aspired to. The key reality was that Kielder’s workforce – as mechanisation took off and communications improved – simply didn’t expand in the way that had been envisaged. Of the three villages built of the eight originally planned, Kielder is about a third of its planned size, Stonehaugh and Byrness about half. As you might expect, Kielder’s 180 houses are now privately owned.

With hindsight (but perhaps with a touch more realism), Sharp’s notion that the village could sustain ‘a dozen shops, a couple of pubs’ seems fanciful to say the least – a harking back to pre-industrial villages rather than a glimpse of a feasible future.

Kielder’s new primary school, built to accommodate 100 pupils, had over 80 when opened. The school roll fell to two at its lowest but had recovered to twelve in 2019 when inspected by Ofsted (and rated ‘Outstanding’). The school buildings includes community rooms and a library. A village shop and post office survives on Castle Drive. And there is a pub, the Angler’s Arms situated near the Castle which is itself now a busy visitor centre for Kielder Forest.

The latter mark the major change to have affected the village – the growth of tourism and the deliberate promotion by the Forestry Commission of the forest as a tourist destination. Kielder Water nearby – a reservoir (civil engineers Babtie, Shaw and Morton; architects Sir Frederick Gibberd and Partners) opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1982 – has added to local attractions.

Thomas Sharp’s unpublished memoirs, poignantly entitled Chronicles of Failure, included the following passage:

I felt that what would most satisfy me in life, what would most justify me ever having lived, what would crown a whole life’s work, would be to build a good new village and write a good, even if very short, lyrical poem.

I’m not sure that he ever wrote that poem to his satisfaction and he was certainly disappointed by the stunted development of Kielder. He might be forgiven for not anticipating some of the major economic changes that would vitiate his optimistic plans but I think we can be kind to his legacy, both the ideals and principles that informed them and the necessarily more modest building bequeathed.

Sources

(1) Gilbert H Jenkins, letter, The Times, 2 October 1935

(2) See ‘Training camps for Unemployed’, The Times, 10 March 1933 and ‘Summer Camps for the Workless’, The Times, 22 September 1934

(3) ‘Northumberland Forest Will Save Dollars’, South Shields Evening News, 9 June 1950

(4) ‘Trees – the Harbingers of a Rural Revolution’, The Yorkshire Observer, 9 June 1950

(5) Quoted in John Pendlebury, ‘Introduction’ to Thomas Sharp, The Anatomy of the Village (Taylor and Francis, 2013)

(6) This and the succeeding quotation are drawn from ‘Two Forest Villages for the Forestry Commission; Planner: Dr. T. Sharp’, Architect & Building News, 15 April 1949

(7) Thomas Sharp, ‘Forest Villages in Northumberland’, The Town Planning Review, 1 October 1955

(8) ‘Rural housing at Gillingham for Loddon Rural District Council; Architects: Tayler & Green’, RIBA Journal, January 1959

(9) Sharp, ‘Forest Villages in Northumberland’

(10) ‘Two Forest Villages for the Forestry Commission; Planner: Dr. T. Sharp’

(11) John Pendlebury, Thomas Sharp’s Forestry Villages: Kielder, Byrness and Stonehaugh, March 1, 2022

(12) Sharp, ‘Forest Villages in Northumberland’, The Town Planning Review

(13) Hansard, Forestry Villages, Northumberland, 30 July 1954

(14) Hansard, Forestry Commission Villages, Northumberland (Amenities), 28 July 1960

(15) Quoted in Leona Jayne Skelton, ‘The uncomfortable path from forestry to tourism in Kielder, Northumberland: a socially dichotomous village’, Oral History, Autumn 2014

(16) Quoted in Pendlebury, ‘Introduction’ to Thomas Sharp, The Anatomy of the Village