Last week’s post looked at the origins and early development of the new town of Kirkby. Despite the ambitions and claims of its planners, some early impressions of observers were critical and the responses of some residents at least were muted, showing gratitude for better housing but a more sceptical attitude towards their new environment.

This image of Kirkby shopping centre in 1964 gives some evidence of the town’s young population © Liverpool Echo

Objectively, two things stand out. One was the age profile of the new town: in 1961, some 48 percent of the population was under 15; the England and Wales average stood at 27 percent. There were reports of serious vandalism as early as 1960 when, for example, the Liverpool Echo, reporting the departure of the local vicar to the safer environs of Southport, described the town ‘troubled by gangs of young vandals who leave a weekly trail of havoc’. (1)

We’ll come back to this issue and it seems far too crude to ascribe it simply to local demographics but it’s noteworthy that in at least two cases of allegedly vandal-ridden estates – the Brandon Estate in Lambeth and Meadowell in North Shields – local commentators blamed their preponderance of young people. (In fact, at 30 to 35 percent, the numbers under 15 were significantly lower than at Kirkby.)

The Peacock public house, Quarryside Drive, Northwood, 2016

The second is criticism of Kirkby’s lack of facilities. We saw last week the genuine efforts to provide health and educational resources but other amenities lagged. ‘There’s nothing for teenagers’, complained one respondent to the 1961 survey of Liverpool academic John Barron Mays. Some commentators linked the town’s young population, its lack of facilities and the allegedly high levels of antisocial behaviour, as a Times report on Kirkby (‘the legendary birthplace of the BBC’s Z Cars’) did in 1965: (2)

Although half the population is under 21 no one has yet built a cinema or dance hall and, possibly for this kind of reason, the 13 and 14-years-olds are the town’s most frequent law-breakers. Shop windows are shattered with monotonous regularity, telephone kiosks are damaged at the rate of one per day and windows of unoccupied buildings are now sometimes protected by corrugated iron.

One of May’s respondents, the 32-year old wife of a brewery manager, stated she couldn’t ‘belong to a club because not an RC’ (sic). Lingering sectarianism notwithstanding, for all the promise as so often the provision of social amenities followed too slowly on the housing drive which preceded it.

Kirkby Industrial Estate, undated © Liverpool Echo

In the 1960s, employment opportunities offered a better prospect. Ronald Bradbury, Kirkby’s chief planner, claimed the Kirkby Industrial Estate was employing 12,000 by 1956, 16,000 by 1961 and 25,000 by 1967. Some of its firms such as Birds Eye, Hygena and Bendix, were the household names of Britain. Jeff Morris recalled his earlier working years in Kirkby: (3)

The industrial estate was a world of opportunity. You could leave one job and walk into another. I think it was the largest in Britain at the time, or at least in the North West.

Full employment Britain seems a foreign country where things were done differently. In the 1970s the post-war compact between state and society that guaranteed jobs and social security began to dissolve and Kirkby in particular would suffer grievously.

In 1971, Thorn Electrical, which had just bought Fisher-Bendix, announced the closure of the company’s Kirkby plant with the loss of 600 jobs. A factory occupation demanding ‘the right to work’ followed and a new owner was found to keep the factory going, for the time being at least.

Tower Hill protest, 1972. The placard on the left reads ‘Tower Hill Flat Dwellers Let’s Have Homes Not Fungus Cells’ – a reminder that this was also a protest about housing conditions.

Such local militancy, this time led by women, was displayed again in a fourteen-month rent strike, involving 3000 households at peak, led by the Tower Hill Unfair Rents Action Group – a protest against the £1 a week increase proposed by Kirkby Urban District Council as a result of the ‘fair rents’ regime of the 1972 Housing Act. (4)

But such struggles availed little against the larger forces at work. As early as 1971, Kirkby was noted as one of several problematic ‘peripheral estates’ – areas characterised by their ‘marked degree of social homogeneity’, rising unemployment and physical decline. By 1981, an unemployment rate of 22.6 percent placed it second in the country after Corby which had recently suffered the closure of its steelworks. (5)

Ranshaw Court, Tower Hill, seen in its brief heyday and demolished, 1982

Kirkby’s physical decline was seen in Tower Hill’s recently built seven-storey system-built maisonette blocks, flawed from the outset and scheduled for demolition barely ten years later. Across the town, three-storey flat blocks – disliked for their lack of space and appalling sound insulation – made up almost a quarter of its homes and suffered an annual tenant turnover of 25 percent. For some, the almost systematic destruction of these flats when empty by Kirkby youth was not mindless vandalism but justified protest. (6)

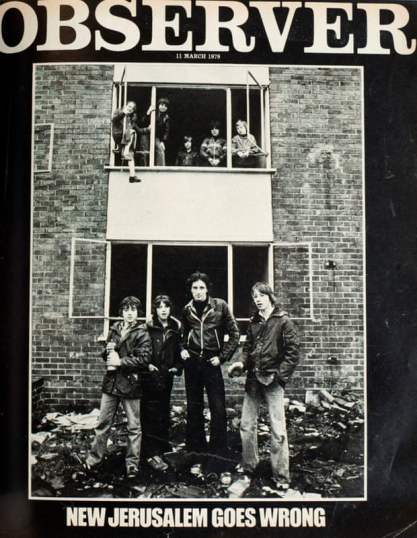

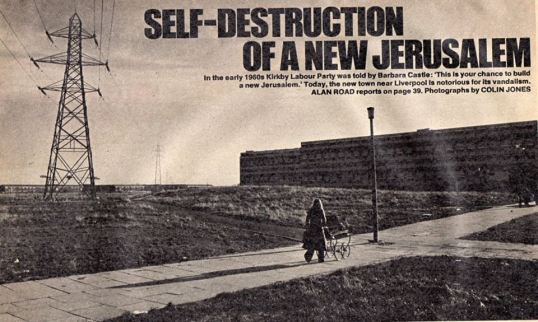

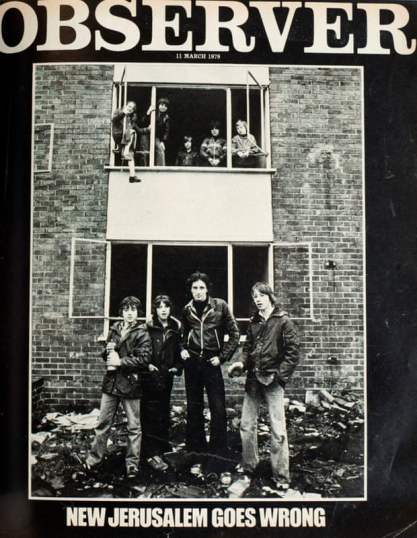

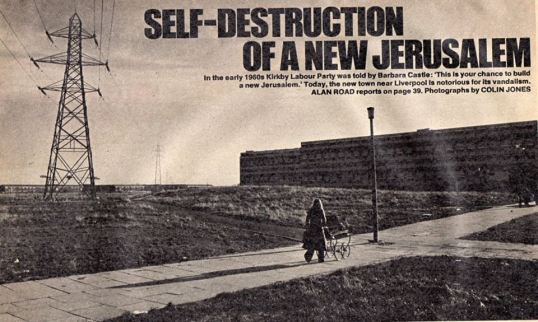

Cover and image from the Observer magazine article on Kirkby in 1979

The forces of law and order were less sympathetic. Chief Superintendent Norman Chapple, in charge of local policing, produced a lengthy report entitled ‘Kirkby New Town: an Objective Assessment of Social, Economic and Police Problems’ in 1975 which received national coverage.

Its statistics made for sobering reading: around 700 council homes were badly vandalised annually; vandalism generally cost the town some £375,000 a year, a figure comparable, it was said, to a town ten times its size; 14,000 streetlights had been destroyed in a six-month period; an average of five telephone kiosks were vandalised daily. In all, Kirkby’s crime rate was 16 percent higher than the Knowsley and Merseyside average, itself said to be the highest in Britain, and the proportion of juvenile offenders arrested was two-thirds greater than in London. (7)

Kirkby town centre, June 1993 © John Wakefield

Chapple acknowledged the context: dissatisfaction with housing, high unemployment, an exceptionally high population of young people and a continuingly high birth rate. And he recognised the depressing nature of the local environment:

The whole atmosphere of the town centre and the four community centre shopping precincts is marred by the fact that most shops have either bricked up their windows or covered them with permanent and unsightly metal grilles.

But he was also unsparing in his character assessment of the town’s population. He suggested that the parents of Kirkby ‘must accept a large part of the blame for the misconduct of the younger generation and hence their own squalid environment’. He observed a ‘high proportion of irresponsible or manifestly anti-social residents’. And he believed:

All endeavours to improve the general quality of life will be vain, however, unless some way can be found to improve the basically apathetic, irresponsible and anti-social attitude exhibited by a large proportion of the community.

Of course, many residents found such judgments shocking and offensive. Earlier letters to the Liverpool Echo had rejected such stigmatisation: ‘Someone tell me just where you think Kirkby people originate. We are not a separate race’, said Mrs Badcock. Joseph and Margaret McCann complained about Kirkby’s ‘undeserved bad reputation’. One ‘Contented Kirkbyite’ noted the ‘very nice respectable people and families who are a credit to Kirby’. Vandalism, most respondents commented, was not specific to Kirkby but a problem everywhere and in places with far fewer young people. (8)

James Holt Avenue, Westvale, 2016

Critical commentary easily lurched into ugly stereotyping and the latter, whatever the reality, merely added to Kirkby’s problems. From somewhere removed in time and place, it’s hard – and perhaps unnecessary – to pass judgement. The seventies seem – this an admittedly anecdotal observation from someone who lived through them – a time of cultural shift; a more troubled and less deferential era. The objective circumstances of Kirkby – poor housing in too many cases, inadequate amenities – warranted grievance. Unemployment, youth unemployment reaching 60 percent, decimated its community; the town’s population fell by 15 percent in the decade after 1971.

And there was, as Chapple noted, though unsympathetically in his case, an anti-authoritarian attitude perhaps rooted in the decades-long experience of a casualised Liverpool docks workforce of ruthless exploitation. Chapple was shocked by the apparently widespread acceptance of the theft and receiving (in police parlance) of stolen goods but ‘nicking’ – as has been noted in Glasgow too – could be viewed as a form of justifiable wealth redistribution by those at the sharp end of social inequality.

The problems and the spotlight – more empathetically in this case – remained on Kirkby in the early 1980s when the Centre for Environmental Studies (CES) researched ‘outer estates in Britain’. Its report on Kirkby and Stockbridge Village (formerly Cantril Farm) – another peripheral Liverpool development – was published in 1985 and noted the ‘chronic state of disrepair’ of much of the housing and the dependence of around half Kirkby’s households on state benefits. The industrial estate’s ‘large-plant, branch-plant economy, making consumer products’ was no longer viable as globalisation impacted and the town’s unemployment rate was 50 percent higher than that of Liverpool as a whole. (9)

The new St Chad’s Health Centre

All Saints Catholic High School, opened in 2010

All this is past history and there has been significant change since. The town was ripe for the area-based regeneration initiatives that characterised government policy from the 1980s onward. Demolition and rebuild in Tower Hill were supported by a £26 million grant from the Estate Action Programme launched in 1985. By 1992, one enthusiastic report claimed the area now had a five-year waiting list of people wanting to move in. Kirkby also received money from the Single Regeneration Budget but the Council’s 1992 bid for City Challenge funding was rejected. (10)

Contrary to received wisdom, New Labour did invest quite heavily in what became known as the ‘left-behind areas’. In Kirkby the results can be seen in new schools and health centres. But secure and decently remunerated employment, given the government’s embrace of a competitive, globalised economy, was a tougher nut to crack.

As was typical, however, the regeneration strategy focused heavily on housing, clearing those areas judged particularly problematic or unpopular. The practical reality of empty and hard-to-let social rent homes in Kirkby and a declining population (from almost 60,000 in 1971 to 40,472 in 2001) made the contemporary policy preference for low-rise mixed-tenure, ‘mixed community’ development an inevitable and, in this case perhaps, justifiable, choice.

Willow Rise (in foreground) and Beech Rise, Parklands, Roughwood Drive, 2016

In 2000, land north of Shevington’s Lane was set aside for ‘a private housing area comparable in size to the original public housing estate’. By 2005, six of the eight 15-storey towers along Roughwood Drive been demolished. Redeveloped by LPC Living and rebranded Parklands, the two remaining towers were refurbished to provide ‘high-quality contemporary accommodation’ for sale whilst ‘40 new two- and three-bedroom mews-style townhouses’ replaced the others. (11)

New housing at Sycamore Drive off Roughwood Drive, 2016

In Southdene, the two eleven-storey Cherryfield Heights blocks have also been demolished. The surviving four eleven-storey blocks at Gaywood Green are now scheduled for demolition due to fire safety concerns. (12)

The almost unavoidable corollary of regeneration was so-called Large-scale Voluntary Transfer of housing stock from local authorities to housing associations – hardly voluntary as councils were denied the support needed to fund renovations and new build themselves. In 2002, Knowsley Council’s 17,000 homes were transferred to the Knowsley Housing Trust formed for the purpose. The Council estimated this would release £270 million of new investment in housing.

Quarry Green Heights, 2016

A tower block fire in Huyton in 1991 (before transfer) was seen as ‘a warning which ultimately went unheeded’ and fire risk assessments issued by the Merseyside Fire and Rescue Service in 2017 relating to the Quarry Green blocks reflected what critics saw as a generally bureaucratic and non-responsive attitude amongst a rapidly changing senior staff. The Trust was issued a non-compliance order by the Social Housing Regulator in 2018 which stated baldly that it failed to meet governance requirements. Since April 2020 it has been re-invented as the Livv Housing Group. (13)

Kirkby shopping centre, 2016

Currently, the twenty-year saga of the regeneration of Kirkby’s town centre is centre-stage with – to cut a long story short – the hopeful news that a Morrison’s superstore, a Home Bargains outlet and a drive-thru (sic) KFC will be gracing the redeveloped centre following a ground-breaking ceremony in January this year. (14)

The current moment (I write in the midst of the Coronavirus pandemic) is hardly propitious to such efforts and the practical and psychological boost of a revived central shopping area will battle unequally against the objective reality of Kirkby’s continuing poverty. In the modern jargon of multiple deprivation, as of 2018 some 34 percent of Kirkby’s population suffered income deprivation (against an English average of 15 percent) and 28 percent employment deprivation (12 percent). (15)

New private housing in Brackenhurst Green, Northwood, 2016

Despite the high hopes – and a degree of hyperbole – which accompanied its inception, Kirkby has not been an unalloyed success though, as ever, many of its residents will have experienced their homes and community far more positively than media headlines and hostile commentary would suggest. Back in 1981, when CES essayed a judgment on what had gone wrong, they concluded that no-one or nothing was directly to blame, except history: ‘the town’s main stumbling block is that “each of the main problems exacerbates the others”’. (16)

That will seem a mealy-mouthed judgement to some. Many would point to planning hubris and, more specifically, the inherent problems associated with large, mono-class peripheral estates. Others would blame poor execution – flawed housing and inadequate amenities. But neither offer sufficient explanation. The necessary context is inequality and a state and society which have in recent decades retreated from the promises of a more classless prosperity that briefly actuated our politics in the era that gave birth to the new town of Kirkby.

Notes

My thanks to John Wakefield for permission to use a couple of his powerful images of Kirkby at this time and for supplying additional detail.

Sources

(1) Quoted in David Kynaston, Modernity Britain: A Shake of the Dice, 1959-62, Book 2 (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014)

(2) ‘Police See Widening Gap with Public’, The Times, 3 February 1965

(3) Molyneux, ‘Kirkby’s transformation from sleepy rural town to “the great new world”

(4) These working-class struggles are described from a left-wing perspective in numerous accounts. Fisher-Bendix, for example, in libcom.org, Under new management? The Fisher-Bendix occupation and from International Socialism, Malcolm Marks, The Battle at Fisher Bendix; the Tower Hill Rent Strike in Big Flame and the Kirkby Rent Strike and ‘”Empowered working-class housewives” – Big Flame, Women and the Kirkby Rent Strike 1972-73’.

(5) Duncan Sim, ‘Urban Deprivation: Not Just the Inner City’, Area, vol 16, no 4, December 1984

(6) Mark Urbanowicz, Forms of Policing and the Politics of Law Enforcement: A Critical Analysis of Policing in a Merseyside Working Class Community, PhD thesis, University of Warwick, 1985

(7) The quotations which follow are drawn from Ian Craig, ‘Kirkby – “Town in State of Crisis”’, Liverpool Echo, 2 December 1975, Peter Evans, ‘Hooliganism and theft make new town a disaster area’, The Times, 3 December 1975 and Urbanowicz, Forms of Policing and the Politics of Law Enforcement: A Critical Analysis of Policing in a Merseyside Working Class Community.

(8) Letters page, Liverpool Echo, 22 November 1972

(9) CES Paper 27, Outer Estates in Britain: Action Programmes in Kirkby and Stockbridge Village (1985)

(10) ‘The town that fought its way back’, The Times, 13 July 1992

(11) Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council, Supplementary Planning Document Tower Hill (Kirkby) Action Area (April 2007) and Parklands, LPC Living and ‘Rush to Buy Tower Blocks’, Liverpool Echo, 21 September 2005

(12) See the Tower Block UK website of the University of Edinburgh and Nathaniel Barker, ‘Merseyside housing association to demolish tower blocks after fire safety failings’, Inside Housing, 15 May 2019

(13) Nathaniel Barker, ‘Knowsley Housing Trust: what went wrong?’, Inside Housing 12 October 2018 and Regulator of Social Housing, Regulatory Judgement on Knowsley Housing Trust LH4343, August 2018.

(14) Chloé Vaughan, ‘Ground breaks on retail development in Kirkby’, Place NorthWest, 31 Jan 2020. The town’s Wikipedia entry contains exhaustive detail on the longer story.

(15) Knowsley Council, Kirkby Profile 2018.

(16) Quoted in Sue Woodward, ‘”Town of Apathy”: the Daily Problems of life in Kirkby’, Liverpool Echo, 19 October 1981

designed to symbolise the functions of the new building with relation to family health – motherhood, various stages of childhood and the spirit of healing.

The basement contained a ‘Tuberculosis Handicraft Centre’ where unemployed TB sufferers could learn craft skills which might lead to employment or might, at least, provide a useful hobby.

The basement contained a ‘Tuberculosis Handicraft Centre’ where unemployed TB sufferers could learn craft skills which might lead to employment or might, at least, provide a useful hobby.This two-fold evil was being resolutely dealt with …Slums were being cleared, overcrowding was being overcome by new housing plans and Southwark was now one of the healthiest boroughs of London.

Early housing legislation such as the Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Improvement Act of 1875 gave local authorities powers to clear entire areas of ‘insanitary’ buildings but few municipalities (with the exception of major cities such as Glasgow, Liverpool and the London County Council) fulfilled the requirement to replace housing lost through slum clearance, and those that did so mainly relied on philanthropic bodies such as the Peabody Trust to undertake rebuilding.

Early housing legislation such as the Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Improvement Act of 1875 gave local authorities powers to clear entire areas of ‘insanitary’ buildings but few municipalities (with the exception of major cities such as Glasgow, Liverpool and the London County Council) fulfilled the requirement to replace housing lost through slum clearance, and those that did so mainly relied on philanthropic bodies such as the Peabody Trust to undertake rebuilding.

The second scheme was more ambitious in the range and size of cottages provided. There were four classes of dwelling: Class A had a sitting room, living room, scullery and four bedrooms; Class B the same but with three bedrooms and Class C had two bedrooms. Class D contained a living room, small scullery, bathroom and two bedrooms. The innovation in this scheme was the use of Cornes and Haighton’s combined range, copper and bath in each cottage. The bath could be covered when not in use. The Class A cottage provided for the larger family, as described with typical Edwardian moral condescension by James Cornes in 1905: (3)

The second scheme was more ambitious in the range and size of cottages provided. There were four classes of dwelling: Class A had a sitting room, living room, scullery and four bedrooms; Class B the same but with three bedrooms and Class C had two bedrooms. Class D contained a living room, small scullery, bathroom and two bedrooms. The innovation in this scheme was the use of Cornes and Haighton’s combined range, copper and bath in each cottage. The bath could be covered when not in use. The Class A cottage provided for the larger family, as described with typical Edwardian moral condescension by James Cornes in 1905: (3)